It may be hard to believe now, but rail tracks once crisscrossed the National Capital Region like lifelines on a palm, foretelling the life of a growing nation. In fact, the birth, expansion and perhaps the key to the Ottawa-Gatineau area clinching the capital title is largely due to the extensive rail system that once ran through the area.

In 1850, what was known as Bytown was officially transformed from a village to a town, but little Bytown had bigger aspirations. With sights of making their town a capital city, local business investors understood the limited transportation of the Rideau Canal, which would essentially shut down in the winter, wouldn’t offer enough opportunity for growth. Railway lines started opening up in the United States, allowing for a greater possibility for trade. A line particularly beneficial to the people of Bytown was set to finish in Ogdensburg NY, which sat across the St. Lawrence River from Prescott ON.

And so in 1850 Robert Bell, who would eventually create the Ottawa Citizen, along with his son-in-law John McKinnon, founded the Bytown and Prescott Railway Company.

The creation of the first tracks in Ottawa took four years, and considerable effort, especially from Walter Shanly, the civil engineer in charge of the rail. Shanly braved the cold Ottawa winters in snowshoes to map out three potential routes for the railway, routes that weren’t navigable during warmer periods since they ran through dense swamp.

Eventually the route was chosen in 1851, but it wouldn’t be operational until 1854.

A myth surrounds the first trip on the Bytown and Prescott Railway, one that in particularly nags at Colin Churcher, an expert historian on rail in the National Capital Region. It’s said that Shanly mistakenly ordered less rail than what was necessary, and that in a pinch to get the first car running by Christmas 1854, he used maple timbers covered with iron straps, known as snake rails, in order to complete the line. This, according to Churcher is completely false, a rumour founded on a mistake in calculation between a 19th century British tonne and what we now know as a tonne. And so the first train rolled into Ottawa without much drama or excitement at all.

Thomas McKay, one of Ottawa’s founders, influenced the north end or the railway to end in his corner. Originally from Perth, Scotland, McKay, a stonemason by trade, put his acumen to good use and one by one, laid the building blocks for the city we know today. In 1838 he built the limestone Scottish Regency mansion as his home, and named it Rideau Hall. He also had a hand in building the locks on the lower end of the Rideau Canal and the stone house that is now known as the Bytown Museum. He was founder of New Edinburgh, which he transformed into a prosperous settlement due to his sawmill and gristmill, both aided by his major investment in the Bytown and Prescott Railway. With direct access to rail, he could make use of the north end of the line to send lumber from the Ottawa River to the St. Lawrence, accessing markets in the United States and Montreal.

In 1855, the Bytown and Prescott Railway adjusted its name to its North end station’s new name, the Ottawa and Prescott Railway. Just three years after Bytown became Ottawa, Queen Victoria chose the new city as the capital of Canada, and in 1859, Bytown’s big dream came to fruition.

The railway was eventually renamed the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Railway company in 1867. The line was so important that it was protected under Section 92(10)(c) of the Constitution of Canada. The federal St. Lawrence and Ottawa Railway Act of 1867 stated: “The Ottawa and Prescott Railway, … is hereby declared to be a work for the general advantage of Canada.” This status still applies to the remaining sections of rail today, and any plan to operate on remaining sections of that route also gain federal regulatory status.

In 1872, the Act to amend the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Railway explicitly extended its authorizations to any other railway company seeking to make use of the rail and the bridge across the Ottawa River.

With these allowances came more rail connections, namely the construction of the rail between Montreal and Hull, and of the Prince of Wales Bridge by the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway (QMO&O), then owned by the Québec provincial government. That line was also declared to be “for the general advantage of Canada”. The QMO&O officially opened the Prince of Wales Bridge in 1880 then, as planned, sold it in 1882 to Canadian Pacific to connect it with their new Canada Central Railway, which connected Brockville, the

St. Lawrence, the Ottawa River, and eventually North Bay.

J.R. Booth took advantage of the possibilities of expansion by rail to create in 1892, the largest lumber mill of its time. In order to outsource his lumber to Québec, Vermont, the Georgian Bay, Booth formed the Canada Atlantic Railway Company in 1897.

By that time, locomotive rail was synonymous with an explosion of business opportunities in the National Capital Region. The area’s electric rail system would be a similar catalyst to the transformation of the city we see today.

Thomas Ahearn, born in Lebreton Flats in 1855, and inventor of the “electric oven,” was the co-founder of electric rail in Ottawa. As a young man, impassioned by electricity, he offered to work for free for the J.R. Booth Company so that he could learn telegraphy. Warren Soper also shared this passion for the telegraphy and electricity, and in 1881 they became Ahearn & Soper, electrical contractors at large.

Together they founded the private sector Ottawa Electric Railway Company (OER), and in 1891, they introduced electric streetcars to Ottawa a year before both Toronto and Montreal’s systems came into action. In its first 11 months, ridership hit 1.5 million, almost tripling the ridership of the horse-drawn streetcars that came before it. The OER connected people across town, and also created destinations like Lansdowne and Britannia Park for passengers to relax during their days off.

On the other side of the river, the Hull Electric Railway was developed by another group of private entrepreneurs, and opened in 1896. The line originally ran from Hull to Aylmer, but in 1901, the first trip was made between Ottawa and Hull in an electric streetcar across the Alexandria Bridge, making the passage between provinces that much simpler. The company was taken over by Canadian Pacific in 1902.

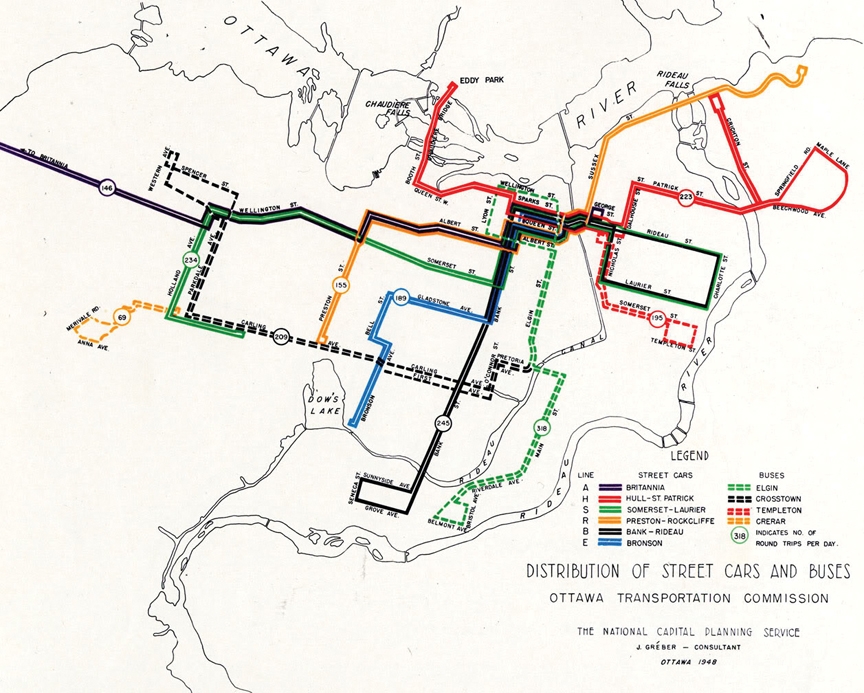

In 1924, the OER introduced buses unsuccessfully, and then again in 1939. Eventually, in 1947, a referendum led by a group of Ottawa city councillors was held and the City of Ottawa took over the OER in 1948. It then became the Ottawa Transportation Commission, or what is now known as the OC Transpo. At that time it ran with 130 streetcars and 61 buses.

It was in 1959 that Ottawa’s love affair with rail began to dwindle. The National Capital Commission’s consultant Jacques Gréber, developed what is now known as the Gréber Plan, which was meant to beautify Ottawa and remove all railways from the downtown area. It then decommissioned Union station, and moved the main train station from downtown out to Alta Vista. As for the electric railways, according to Churcher, revamping a whole new system seemed too costly for the city, and buses promptly replaced the old streetcars. In the coming decades, many of the tracks once laid to connect the city within and without were ripped out to make room for major roadwork like Nicholas Street and the Vanier Parkway.

And yet, there are many who have kept the spirit of the region’s railways alive. The Ottawa Valleys Associated Railroaders are committed to the history of rail in Ottawa, and their site, The C. Robert Craig Memorial Library, hosts one of the best historical collections of associated photos and references.The Bytown Rail Society has been in town since 1969 and works under federal government statute to encourage interest in Canadian railway history. The Ottawa Railway Historical Circle, of which Churcher is a member, meets bi-weekly to discuss matters of the history of rail and works on extensive historical publications about rail in the area.

Today, as global interest shifts back to the efficiencies of passenger rail, Moose Consortium, formed by a dozen local companies, is working to finance, develop and operate a commercial passenger rail service on 400 km of existing track in the National Capital Region. Their bi-level modern trains would once again connect Ottawa and Gatineau, and both these locations to six semi-rural towns throughout the Greater National Capital Region. Like the original developments by Ahearn & Soper and their Hull counterpart in the 1800s, Moose is planning to develop and operate its service commercially, without dependence on taxpayers. And as a nod to Ahearn & Soper, Moose’s application for development to Transport Canada was timed to be on the 125th anniversary of the Ottawa Electric Street Railway Company in 1891.

The people behind the scenes at Moose are themselves a product of the long history of rails that once served as arteries through the heart of the National Capital Region and elsewhere.

“It’s been my passion for making ecological economics tangible that pulled me into railways”, he said. He has honed his economic expertise on the concept of the “Property-Powered Rail” commercial financing model that he describes as the financial engine-of-change driving of the Moose initiative.

Peter Gabany is a long-time friend of Potvin’s and a director of communications at Moose. The two went to high school together back in Welland. Gabany’s long friendship with Potvin and his own expertise in transportation has meant that he’s been with Moose since its fledgling years.

Gabany’s interest in transportation began in the Great Lakes, where he worked and travelled on freighters. He then met up with Potvin to work in Canadian arctic, where they shared an old train dining car as a home. Eventually, Gabany left the North to begin his own company, Limelight, an advertising and design company, that still focuses heavily on transportation and shipping clientele.

Wojciech Remisz, another founding director of Moose, and a civil engineer by day, says that trains are a family tradition. His grandfather was a train stationmaster in Poland, and his father became a structural engineer and worked on railway bridges in Lwow, Poland (now known as Lviv in Ukraine), and then on streetcars in Poland. Due to heavy taxes from a new government, Remisz’s father had to leave the rails and instead opened a hardware store where Remisz said the nuts and bolts and various parts of streetcars were his childhood toys. He then decided to follow in his father’s footsteps, specializing in the design of “iron roads’ as an engineer first in Poland, then after a short pit stop in Rome, he came to Ottawa in 1982 to continue his work.

“A few hundred bridges later,” said Remisz, “I am passionate about rehabilitation of the Prince of Wales Bridge. I feel steam in my blood that keeps pushing me to achieve this goal.” Moose plans to re-purpose the Prince of Wales Bridge for its true calling, to use the tracks to once again connect the National Capital region by passenger trains, but with a cycling path cantilevered off the upstream side, and a pedestrian path on the downstream side overlooking Parliament.

Bill Pomfret is another founding director at Moose and he is the man in charge of safety.

He has designed and patented the 5 Star Health & Safety Management System which has been used internationally, including in the tremendous Mass Transit Railway project in Hong Kong. That system includes 218 km of rail with 155 stations, including 87 railway stations and 68 light rail stops. Now he has dedicated his rail safety expertise to Moose.

Scott Ivay is the lead railway operations member of Moose Consortium. Like many of his compatriots, Ivay comes from a sort of railway dynasty; his great-grandfather, grandfather, and father all worked for Canadian National at one time or another.

“I got my schooling in college, but I got my education on the railway,”said Ivay, who first experienced the rails in the midnight rain working the Vancouver yards and then in the mountain region of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers.

Mark Brandt is another of the five directors of Moose and a conservation architect and urbanist by trade. He’s best known as the award-winning architect behind the reinvention of the former Bank of Montreal across from Parliament Hill, which he transformed into the House of Commons Hall of State. His circuitous road to Moose began in Rome in the 1980s, where he studied architecture and heritage conservation of the eternal city. He then spent three months riding trains on a Eurail Pass to backpack through eight countries.

“I didn’t realize until a decade later that Europe taught me how to appreciate the value of the previous layers of our environment and the need to understand our times in terms of the long game. I understand now how everything is connected – static architecture is intertwined with the people who move through and around it.” It is those long-term values that have led him to Moose Consortium, as lead architect for its “Linked Localites” concept, and at least three dozen start-up stations designed to be deployed like Lego blocks, which can be smartly adapted from former railway shipping containers.

The bones of Ottawa’s railway system still persist. There are nods to it everywhere from the old Union Station, soon to be the home of the Senate, to the lesser known streetcar station underneath the Chateau Laurier, where you can rent bikes in the summer months. But mostly, it lives on in the efforts of those today who want to re-establish one of the best modes of transportation and expansion this region has ever seen.