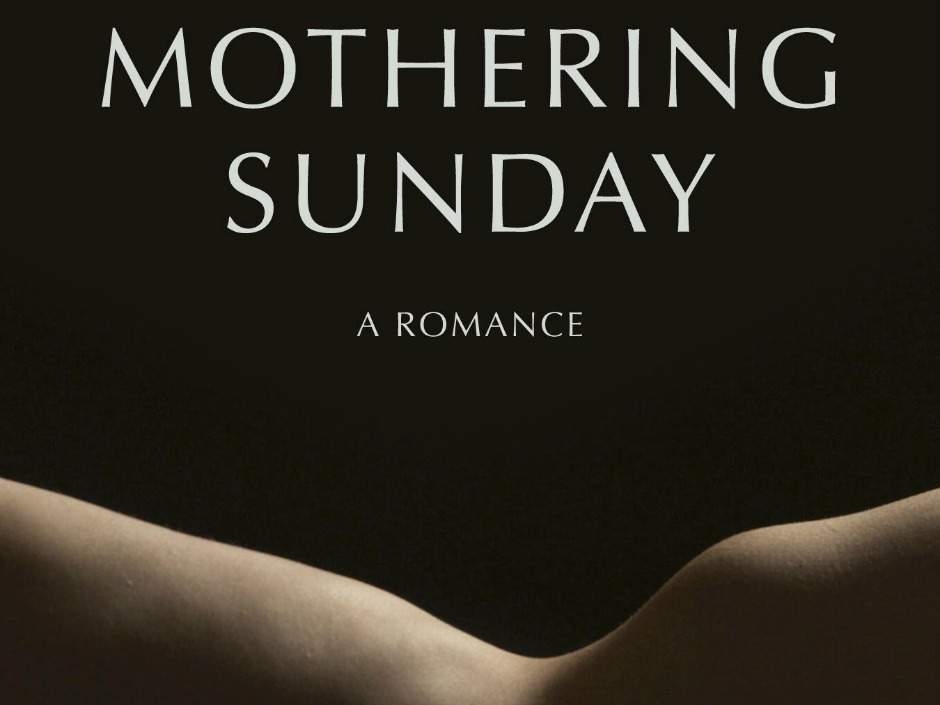

Book Review: Mothering Sunday

Graham Swift’s latest novel explores the mystery of a woman discovering herself

The premise of Graham Swift’s slim, new novel Mothering Sunday is familiar: the arc of a human life is sometimes altered by the most innocuous and unexpected of developments.

It’s March 1924 and Jane Fairchild is a maid living in Berkshire, England. Jane and her lover Paul are sharing their last day together before Paul marries another woman. It’s Mothering Sunday. Paul’s family and their servants are out of the house and Jane has been given the day off by her employer, Mr. Nivens. Their late morning liaison in Paul’s home must be of short duration. Paul has a luncheon to attend with his and his fiancé’s family. As it turns out, he will allow himself to run late, but not so late as to cast doubt in his fiancé’s mind about his desire to marry her. Everything Paul does on this day is carefully calibrated. There is a small window of opportunity and both he and Jane seize it.

So too does Swift himself. His prose is masterful: it’s at once spare, concise, layered and sensual. This is the novel’s greatest attribute. The scene in question is straightforward enough: two lovers languorously passing a morning in bed on an atypically warm day in March. Nevertheless the reader is not sure of the nature of their connection. Is it inspired by love or convenience? Is it their contrasting places in the social order – he the son of an aristocrat, she a maid in the service of another aristocrat – that prevents them from making public their union? Or is Paul, like so many aristocrats before him, merely exploiting his privilege to satisfy his sexual needs? Paul maintains a measured distance even as they’re lying naked together, but Jane is seemingly at ease with their arrangement. Her expectations of Paul do not seem to exceed what he’s in a position to give.

Paul does not want Jane to rush off on account of his leaving. She has no intention of doing so. It’s her day off and, not having a mother, Jane has no one with whom to celebrate the special day. Besides, she’s not ready for this opportunity to bask in the afterglow of lovemaking to be over. She does not need to be back at her own home until much later in the afternoon. The best moments in the novel feature Jane walking around a large, empty house she’s in for the first and last time completely naked. She’s taking a big risk in doing so. What if someone living at the house was to suddenly return? What if Paul’s fiancé arrives at the house looking for him? What would she think as she approached and saw an unfamiliar bicycle parked out front? In more ways than one, Jane is exposed.

In various respects, Mothering Sunday is a novel about modernity. The Great War was, of course, the most brutal manifestation of this ushering in of something new. That four year exercise in barbarism casts a long shadow over the wealthy aristocrats in particular. Sons have been lost to fighting. Their grief renders them numb to changes swirling in the air, changes characterized by the gradual erosion of seemingly rigid hierarchies. As a maid Jane was aware of her place, not only in the Niven’s household but in the wider society. Swift crafts wonderfully revealing sentences highlighting the contradictory expectations employers had of their maids: to be at once present but invisible, knowledgeable but discreet. Everything they do is in the service of their employers. A maid’s inferior social standing by definition means she is intellectually inferior as well. But Jane has stirrings, emotional, physical and intellectual. She will eventually shatter the social expectations surrounding herself.

Swift’s novel, however, is as much about chance as it is about modernity. The afternoon spent first making love and then walking naked and alone in someone else’s house was not an experience Jane could have expected to have when she woke up that morning. Yet it initiates a process of self transformation and discovery that ultimately alters the trajectory of her life. For a time that afternoon she becomes like a ghost, at once familiar and unfamiliar to herself. At one moment she looks at herself in a large mirror, as if for the first time. She knows it’s her, but senses dimensions that she hitherto didn’t know she possessed. What she also senses is the prospect of liberty: in those moments spent gazing at her naked reflection she perceives the possibility of being something other than what she believed she’s destined to be. The prospect is at once exhilarating and terrifying. It’s hard to imagine that the same sort of transformation would have occurred had there never been this sort of detour in the familiar path of her everyday existence.

Related: An Imperfect Offering.

Through Jane, Swift has struck a tone of optimism and possibility. She defies odds. However, Swift doesn’t pretend to render her life in its entirety. Nor is Jane’s transcendence merely attributable to modernity or chance. Her good fortune also flows, in a real sense, from other people’s shared tragedy. In the end, Swift seems to be suggesting there is a deeper mystery to the direction a life takes. Mothering Sunday doesn’t so much explain the mystery as celebrate it.