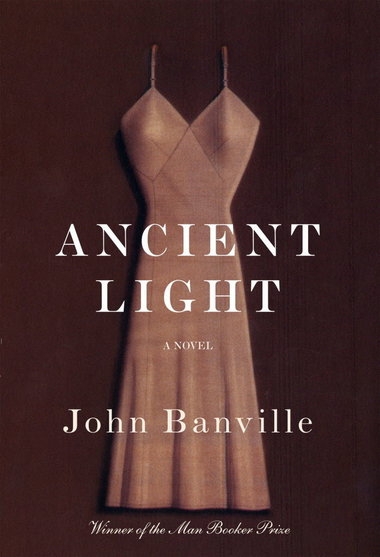

Distant Stars – John Banville – Ancient Light

John Banville – Ancient Light

Vintage Canada 2012

Reviewed by Don MacLean

Readers familiar with the great Irish writer John Banville will also be familiar with the characters Alexander (Alex) Cleave, his wife Lydia and their troubled daughter Catherine (Cass), all of whom feature prominently in some of his previous works. They do so again in Banville’s most recent novel, Ancient Light. The story is told by Alex and revolves around two events central to his life: his torrid affair started in his 15th year with his best friend’s mother, Mrs. Gray and the more recent suicide of Cass. The affair and the suicide are separated by over half of Alex’s life and are seemingly unrelated. We read with the expectation that at some point the connection between the story’s disparate parts will be revealed.

Alex has a complicated relationship with the past. He excavates it incessantly without necessarily trusting what he discovers. At one point he uses stars as an analogy to explain both his fascination and wariness. Like a star, that which happened long ago sends a light that takes years to reach its destination and illuminate. This, in a sense, is the role of memory in the human experience: to use that light from the past to make sense of one’s life then and now. The problem, of course, is that memory is an imperfect filter. Or to use a more exact metaphor, the prism through which the light from the past is distilled can distort as much as it illuminates. Memory, in other words, is fallible. People forget. What we do recall is often embellished or sometimes not true at all. “Images from the far past crowd in my head and half the time I cannot tell whether they are memories or inventions” Alex tells the reader at the novel’s outset. And so we are never quite sure if his recollections of making love to Mrs. Gray in secret places are accurate or mere tricks of the imagination.

Nevertheless, there remains a sense that in recalling their affair Alex is attempting to recover the sense of wonder and newness that is the privilege of youth and too often a casualty of age. Readers of a certain vintage will identify with his impassioned reveries. What middle aged man or woman can’t recall those first kisses or other acts of intimacy shared in the back seat of a car or the basement your parent’s house? For Alex that magical stretch of adolescence was wrapped in additional layers of mystery and complications. Why, he wonders, would a married woman more than twice his age and the mother of his best friend be drawn to him? Why would she want to introduce him to the life of the flesh? He doesn’t know and doesn’t much care so long as Mrs. Gray was intent on swimming naked with him or making love in the back of her station wagon. But for all of his adolescent joy, Alex can’t avoid the complications stemming from their unlikely liaison. He allows it to tear asunder his friendship with his best friend. He is occasionally aggressive towards his older love and, like most 15 year old boys, horribly jealous. He believes Mr. Gray is a boring oaf and secretly imagines doing violence towards him. If the affair is a test of Alex’s maturity, he often fails.

In the present Alex is more or less a retired actor when he’s asked to play the role of a famous individual whose biography is to be the basis for a movie about his life. He accepts and in so doing establishes a tenuous connection between the man he’s playing and Cass, his deceased daughter. The two were residing in the same city at the time of Cass’s death. Alex has reason to believe they knew each other. If so, could he have had something to do with her deep unhappiness? Not likely, but any possible connection is enough to concentrate Alex’s thoughts on his daughter’s suicide and the unresolved questions it left in its wake.

Although Banville’s prose is uniformly beautiful, the sections in which Alex describes his and Lydia’s relationship with Cass are the most poignant. This is in part because in talking about his wife and daughter Alex is at his least self absorbed. He reveals a vulnerability and generosity of spirit that isn’t always evident in his recollections of his affair with Mrs. Gray. Although he and Lydia are equally bereaved, Lydia strikes the reader as the more tormented. Alex talks of Lydia’s night time episodes of sleepwalking, during which she is convinced of Cass’s presence in their home. He must follow her as she wanders around their dark, empty house in a fruitless search to find their dead daughter. There is something not only deeply sad about these scenes, but beautifully mysterious as well. Neither Alex nor Lydia believes in the promises of religion: they don’t expect Cass is attempting to communicate with them from somewhere in the afterlife. But her death doesn’t mean Cass’s absence. She has a ghostly, haunting presence that serves to draw them back to a time when she was alive.

Banville is hardly mining new territory in Ancient Light. The themes of adolescent love, the relationship between the past and present and suicide and loss are as old as literature itself. And although there are some intriguing twists, the story isn’t what one could call plot-heavy. The language in which it is told, however, is unfailingly unique. Indeed, as is true of any Banville novel, the story is as much about the prose as it is the plot. Reading him is like listening to a virtuoso performance by one of the world’s great pianists or guitarists. From the opening page you immediately recognize you’re in the presence of a master who remains at the height of his considerable powers.

How terrible it was to witness Mrs. Gray caught up in such innocent enjoyment – the innocence more than the enjoyment was what was terrible, to me. She sat there, canted backwards a little, her face lifted in dreamy ecstasy to the screen and her lips parted in smile that kept trying to achieve itself but never quite succeeded, lost as she was in blissful forgetfulness, of self, of surroundings and, most piercingly, of me.

There are few writers who can string together words in ways that are as consistently unique, challenging and beautiful. Although he is often humorous, Banville’s prose is marked more by a combined sense of melancholy and loss. Given his fascination with the past, this is fitting. As Alex suggests, the past can be mined but never recovered.