Sometimes Compensation is the Road to Closure

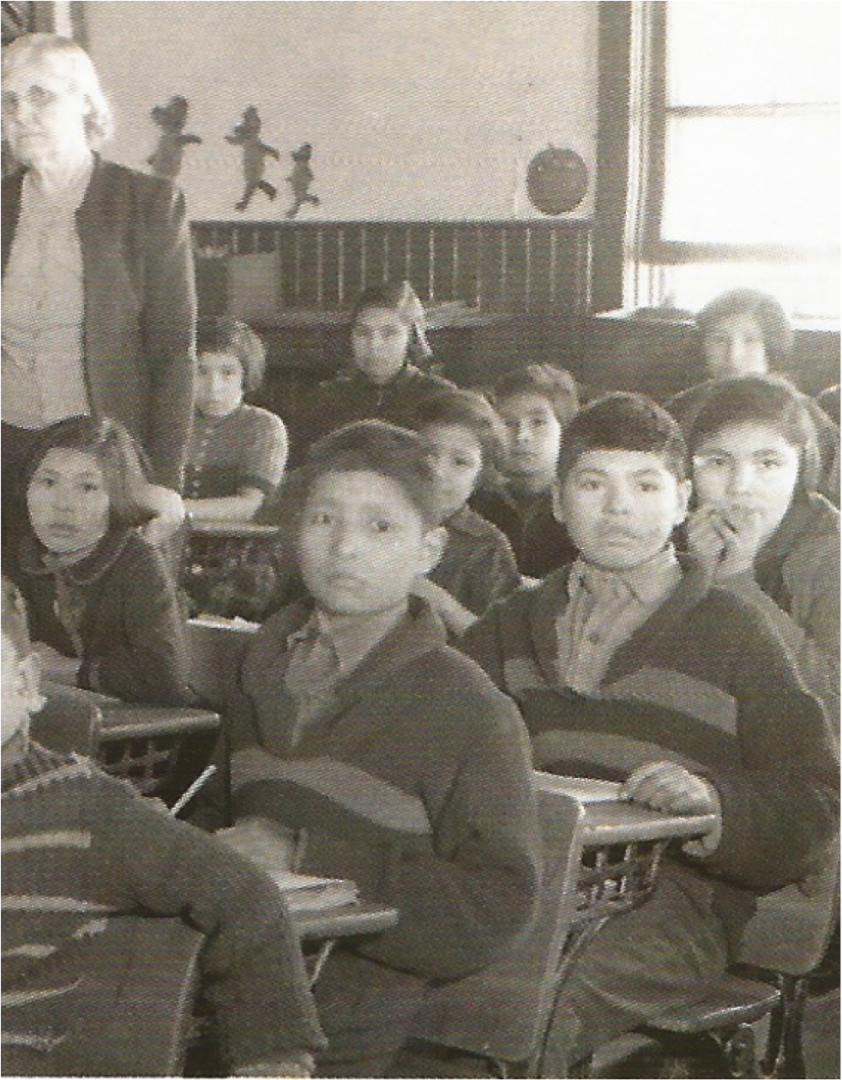

For more than 150 years, the Government of Canada attempted to assimilate aboriginal children by placing them in residential —otherwise known as boarding — schools. Since it was too difficult to change adults, they began “Christianizing” children as early as age five. But over the years, tens of thousands of students were beaten, raped, sexually assaulted, confined, verbally abused and emotionally traumatized during their attendance at these religious schools.

Although legal claims of abuse didn’t surface until 1990, they had escalated to over 7,500 within eight years. Canadian courts were inundated with lawsuits brought against the Government of Canada by residential school survivors — all sought compensation, for physical or sexual abuse — sometimes for both —, for loss of language and culture, and for many other reasons.

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) wanted a way to deal with these claims more efficiently and effectively than the court system, and the survivors, as well as the Liberal government, agreed there needed to be a change. “We realized early on that the courts were not going to be sufficient or efficient,” explained AFN Chief Phil Fontaine.”There were too many claims and the courts were too adversarial”

The Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) process was created through Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada (IRSRC) in 2001 as a “holistic” alternative to court proceedings. Hearings would be private. Some legal and travel costs would be covered.There would be no cross-examination or questioning. Decisions would be reached within 90 days — instead of up to three years for decisions made through the courts.

“Our ADR approach is groundbreaking,” claimed the Hon. Anne McLellan, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and the Minister Responsible for Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada, earlier this year at an evidence hearing for the Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Northern Development (AANO). “(It is) a culturally-based humane and holistic way to provide additional choices for former students who are seeking compensation for sexual and physical abuses.”

But ADR isn’t groundbreaking — it’s bank-breaking. Department expenditures tripled over the years, from $42 5 million the year of its inception to a requested $121 million at the 2005 budget. Of the already $275 million spent, it is estimated that only 20%-25% of funds have gone to residential school victims (see graph). In fact,ADR only attracts a small proportion of the claims made.A little over 1,500 claims have been brought to the ADR process up to now.The average cost to settle a case through ADR is just over $180,000, but the average payout is a mere $44,886. Including the requested 2005 funds, IRS will have expenditures totaling $396 million. It has settled less than 10% of its caseload and less than one per cent of all Indian residential school claims.

Even more upsetting is the money spent on appeals. The Hon. Jane Stewart, then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, read from the Statement of Reconciliation in 1998: “To those of you who suffered this tragedy at residential schools, we are deeply sorry.” But how sorry could the government be as it spent an estimated $20,000 to appeal 88-year-old Flora Merrick’s $1,500 physical abuse settlement?

Adjudicator Terrence Chinn had awarded Merrick the money because her memories of “this harsh incident… bother her greatly to this day.” She had testified to being confined with her sister in a dark room for two weeks for crying after their mother died, as well as being strapped so severely that black and blue marks remained on her body for weeks.

Shortly after Merrick settled her case, the ADR program’s chief adjudicator received a letter from the deputy minister of IRSRC, Mario Dion, asking him to overturn the Merrick decision on the grounds that the strapping was appropriate for the time and that Chinn was wrong to award any compensation.

Dion’s spokesperson Kirsty Jackson told the National Post: “The government requests this review reluctantly; however, we have a duty to ensure that all awards fall within the mandate of this process.” After all, the beatings Merrick endured were deemed “appropriate for the time.”

“I was willing to accept the $1,500 award, not as a fair and just settlement, but only due to my age, health, and financial situation,” Merrick explained to the AANO. “I wanted some closure to my residential school experience. I am very angry and upset that the government would be so mean-spirited as to deny me even this small amount of compensation.” Merrick withdrew from the ADR process and has since opted for a legal battle in court.

So much for the government’s holistic method.

ADR was applauded by the AFN and survivor groups for providing an out-of-court settlement process, which for the most part means claimants who are awarded compensation will receive it more quickly and with less stress and expense than through the court system. It offers a more flexible process, some costs are covered by the government, and victims are given a chance to tell their story without questioning. But that’s just about all the good involved. Although these specific aspects arc encouraged by the AFN, it has not overall been well received by the AFN or survivors. With good reason: the process treats survivors differently in more than one regard.

ADR is broken down into two categories: sexual assaults (Model A) and physical assaults (Model B). The categories are capped at $245,000 and $3,500, respectively. However, that $245,000 dwindles to only $195,000 if the abuse took place outside British Columbia, Ontario or theYukon. Compensation is awarded depending on the severity of the act and not at all on the abuse’s lasting effects, including emotional damage and the loss of language, culture and family life.

Monetary compensation decreases further, depending on whether or not a church was involved in the claim.The government is only willing to pay 70% of awarded compensation where a church was named in the lawsuit. Although the Anglican and Presbyterian churches, as well as a mere four Roman Catholic dioceses, have agreements to cough up the remaining 30%, a claimant is out that portion if he or she attended any of the remaining Catholic and United residential schools. Catholic-run schools alone make up over 50 % of the Indian residential schools.

“The government continues to deny them justice as it unconscionably tries to defend the indefensible,” Merrick’s lawyer Dennis Troniak said at the AANO hearing. “So I ask (…) any parliamentarian who stands in the way of justice on this issue, “Have.you no shame?”‘

The lack of closure provided, and the significant amount of time it has taken to compensate a mere one-eighth of the survivors has not at all gone unnoticed. The AFN released a comprehensive report outlining ADR’s shortcomings and what the government can do to offer reconciliation and promote healing.

The changes recommended to the ADR process and the other requests are simple and the AFN Report is endorsed and supported by AFN Chiefs, survivors, church groups, lawyers, the Metis National Council, the Native Women’s Association of Canada, experts in the field of reconciliation, and the Canadian Bar Association (CBA).

“The Statement of Reconciliation was the first big step,” says Fontaine. “But we’re still looking for an apology, a Truth Commission, one compensation grid and an improved process for sexual and physical abuse victims.”

It is recommended that the consequences of abuse are weighed more heavily than the acts; that gender differences are accounted for in the calculation for abuse; that the acts of abuse are judged by today’s standards; and that race discrimination and the undervaluing of harm to survivors in the awarding of compensation be avoided.

Notably, the AFN has asked for payments to upwards of 87,000 survivors. The first portion would be a $10,000 lump sum to “compensate for the loss of language and culture” regardless of whether further harm was suffered. The second portion would be $3,000 for each year or part-year of attendance at an Indian residential school to cover emotional harm, including neglect, forced labor, inferior health care and depersonalization.

No hearings would be involved and payments would be calculated strictly on the basis of school records.

The CBA released its own report in February 2005 and furthered the fight for lump sum payments. “The payment would not require a person to prove that he or she was a victim, but rather would recognize a person as a survivor of an injurious program for which the Government of Canada is responsible.”

Using the current ADR model, it will cost taxpayers $4.4 billion, disregarding inflation, over a period of 53 years to settle 20,000 claims. Claimants are dying at a rate of four to five per day on average and the rate will only increase with each passing year. The average residential school survivor is already 59 years old. Meanwhile, the AFN model could save up to $1.5 billion, compensate the remaining 87,000 survivors, administer all lump-sum payments within two years, and settle all Model A claims within five years. Over 80% of the expenditures proposed by the AFN would go directly to the victims, while only 20 cents to the dollar would be tied up in administrative costs. It’s the complete reversal of the Liberal’s 2003-04 IRSRC expenditures.

Although Fontaine worried that the AFN’s efforts would dissipate somewhat should the Conservatives take over, if only because the AFN has been dealing solely with the Liberals since 1993, his worries could be unnecessary. It could be that all this political upheaval has been a good thing: the Conservatives are looking for reasons to point their fingers at the Liberals, and Martin’s government has given them a very good reason to point. Prentice says this is an issue Conservatives have been concerned about and that the Official Opposition took notice when it saw the amount of money being spent on administrative costs.The IRSRC had become “less, not more, efficient over time,” according to Prentice.

Additionally, the AANO report, which supports the AFN report, “was approved without the support of the Liberal members,” Prentice told the House on April 11, 2005. “It was achieved only with considerable effort on the part of the opposition parties to craft and arrive at recommendations which we could all support and which were brought before the House to get the debate on the floor of the House of Commons.”

On May 4, 2005, Canadian Press (CP) released an article that claimed the Liberals were “considering lump-sum payments and new healing programs as part of a multi-million dollar plan.”Although the story went on to say that the Liberals and the AFN had worked closely “on a deal that could be announced by month’s end,” Fontaine wasn’t aware of an upcoming announcement. He said, “I think we’re close. I think even she (McLellan) has accepted it’s the way to go.” IRSRC Communications stated clearly on the phone rhar the CP story was “absolutely not true.”

Not even two weeks after the Liberals survived a May 19 non-confidence motion by a single vote, McLellan made the announcement that a deal had finally been struck with the AFN on an overall and final settlement for all residential school survivors—a complete 180-degree turn since until recently McLellan had stood firm in her belief that survivors should have to prove damage specific to sexual or physical abuse as described in the ADR program description before receiving any kind of compensation.

Former Supreme Court Justice Frank Iacobucci was named special mediator for the deal. He has been tasked with finding “a settlement package that will redress payment for former students, a truth and reconciliation process, community-based hearing, commemoration and an appropriate ADR process that will address serious abuse as well as legal fees.”And although McLellan would like him to come up with this package “as soon as possible:’ he has until March 31, 2006, to do so.

“As Federal Representative:’ said Minister ofJustice andAttomey General of Canada Irwin Coder, “Mr. Iacobucci has been given a mandate to lead discussions towards a fair and lasting resolution of the residential school legacy.”

So the AFN now looks to Iacobucci, not McLellan, to support its research and agree to an apology and mass compensation.

But what more can Iacobucci do and why does he need 10 months in which to do it? What discussions can he lead that the CBA, AFN or IRSRC has not yet held? And if so many groups and organizations support the AFN documentation that came about after months of debate, research and interviews, does Iacobucci really need any more than two hours to read the document and stamp his approval?

Critics passed off Iacobucci’s involvement as a Liberal stall tactic. It seems to be one more hoop through which survivors need to jump — and these people have jumped through enough hoops to get where they are today in an effort to close the book on their past.

Metis National Council President Clement Chartier, a residential school survivor himself, told Ottawa Life: “The AFN did the right thing and I’m pleased with their progress to date. I hope [Iacobucci’s decision] is going to provide an adequate solution.”

“We’re talking about closure, finality, fair and just compensation,” says Fontaine. “It’s all included in a lump-sum payment. It would be a significant achievement. It would right a historic wrong. It would be good for Canada, and it would set the record straight. If we get this, it’ll be one for the ages. For me, nothing will ever top that.”

By: Paige Beckett