Light Rail: Fast trains for Ottawa will be slow in coming

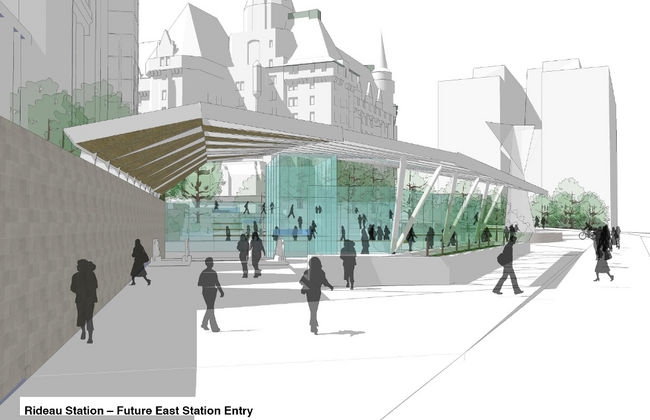

JUST IMAGINE THE TRAVEL OF THE FUTURE IN OUR NATION'S CAPITAL. YOU'VE FLOWN IN FROM EUROPE. AFTER CLEARING CUSTOMS AT OTTAWA MACDONALD-CARTIER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, YOU TAKE A SHUTTLE SERVICE OVER TO THE LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT) STATION BUILT RIGHT NEXT TO THE MAIN AIR TERMINAL, AND HOP ABOARD A SLEEK TRAIN HEADED DOWNTOWN.

The diesel-powered train pulls out of the station and glides along the one-kilometre branch line leading into the airport before hooking up with the main line. The train runs parallel to the Airport Parkway, moving north through Greenboro, the Confederation Heights office cluster, Carleton University, the tunnel under Dow's Lake, past Carling Avenue and along a rock cut to the Lebreton intermodal bus-rail station, where the LRT service intersects with OC Transpo's east-west transitway (or bus-only roadway).

From there, it's only a short hop downtown. You transfer to a bus hassle-free: no need to purchase another ticket. The same one can be used for both rail and bus service. You arrive at your destination relaxed and refreshed.

Or, say you're a busy high-tech executive in town for the day. You grab the LRT from the airport and disembark at the Greenboro intermodal station, where CP Rail's north-south and CN Rail's east-west lines intersect. You kill time at the station's shopping mall, waiting for the westbound train coming in from Ottawa Station. You step on board, work on your laptop as you sweep through Colonnade Business Park, Merivale Industrial Park, and Bell's Corners (where a branch line veers off, serving the Moodie Drive axis and the enormous Nortel campus).

Eventually, you reach your destination: Kanata North Business Park, Canada's answer to Silicon Valley.

A 1.5-kilometre spur line takes you into the massive Newbridge Networks Corporation complex on March Road. After your business is settled and you're seeking a little R&R, you take the train over to the Corel Centre and catch a Senators hockey game or monster truck show.

This seamless transportation network — interlinking rail and bus — could be a reality in the National Capital Region by the year 2021. It is the dream of rail advocates such as Darrell Richards, a consultant with Transport Concepts, and Barbara Ramsay, chair of the Public Advisory Committee on Commuter Rail of the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton (RMOC) and owner of a Shopper's Drug Mart in Nepean.

But it is a dream that is slowly inching its way to reality. According to the RMOC's 25-year official plan, approved by regional council on July 9, a test run has been set for the year 2000 to demonstrate the viability of LRT in the region. Even though the start date was moved up from 2006, Richards still thinks regional government is dragging its heels.

"I'd like to see something sooner," he said. "We need a trial run now to get a feel for how well the system will operate. There are still a lot of anti-rail naysayers out there who have to be proven wrong. I believe the CP Rail corridor (from Lebreton to Greenboro) has the biggest market potential on the shortest stretch of track with the least amount of investment required."

(The line is due to close by the year 2000, according to a spokes-man for the St. Lawrence & Hudson Railway Company Limited, the eastern division of CP Rail. Should this occur, the tracks will likely be torn up and responsibility for the right-of-way will devolve upon the region, making introduction of a commuter rail service a less attrac-tive option, in the opinion of many local rail transit enthusiasts).

"The bus transit 'experts' haven't been very good at factoring in end-user service requirements," Ramsay pointed out. "The local business community does not support a bus-only transit system. We need an intermodal option in Ottawa-Carleton because we are now dealing with major corporate players who want a fast transit service and easy movement around the city for their employees and clients. LRT gives us this badly-needed alternative?'

(In 1993-94, Ramsay chaired the National Capital Transportation Task Force, an Ottawa-Carleton Board of Trade initiative to promote a commuter rail service on CP Rail lines linking Gatineau and Aylmer to Leitrim, near the airport. This proposal, known as the Inter-provincial Commuter Rail Appraisal Study, went nowhere, and was turned down by both the RMOC and the Outaouais Urban Community. The Aylmer-to-Hull track has since been torn up).

"The transitway wasn't a bad idea, but the choice of technology was," Richards opined. "The light rail option is aimed at intensifying public ridership. It will actually increase bus ridership, enticing more people from their cars.'

Even with a full 39.5-kilometre rail network in place, 95 per cent of all daily commuters would still be riding the bus. Richards noted that OC Transpo's ridership peaked at 87 million when the first link in the transitway was built in 1984. Despite a steady extension of bus-only roadways since then, the most recent statistics show that ridership dropped to 71.8 million in 1995 and to 64.8 million in 1996, although the sharp drop in 1996 was mainly due to a 24-day transit strike in November—December.

"Clearly, higher fares for reduced service hasn't worked," Richards said. "OC Transpo needs a new game plan. The main thrust of the transitway is to bring riders to the city centre. Yet downtown federal office buildings are being emptied while most of the explosive growth is taking place in the suburbs, which are poorly served by buses."

Richards also questions the transitway's cost. Promoted as a less expensive alternative to LRT by OC Transpo's former general manager John Bonsall, the transitway is now prohibitively expensive: extending it a mere four kilometres from the Lincoln Heights Galleria to Acres Road near Bayshore Shopping Centre would cost about $130 million. Tunnelling and housing demolition on the one-kilometre stretch nearest to Lincoln Heights would account for $60 million of that cost, Richards said.

"When the transitway concept was sold to regional council, Bonsall promised a 31-kilometre network that would cost only $91.7 million," Richards said. What the region ended up with was a 26-kilometre network of exclusive busways and 24 transitway stations, costing about $440 million. By contrast, Calgary's 30-kilometre LRT system came in at around $500 million.

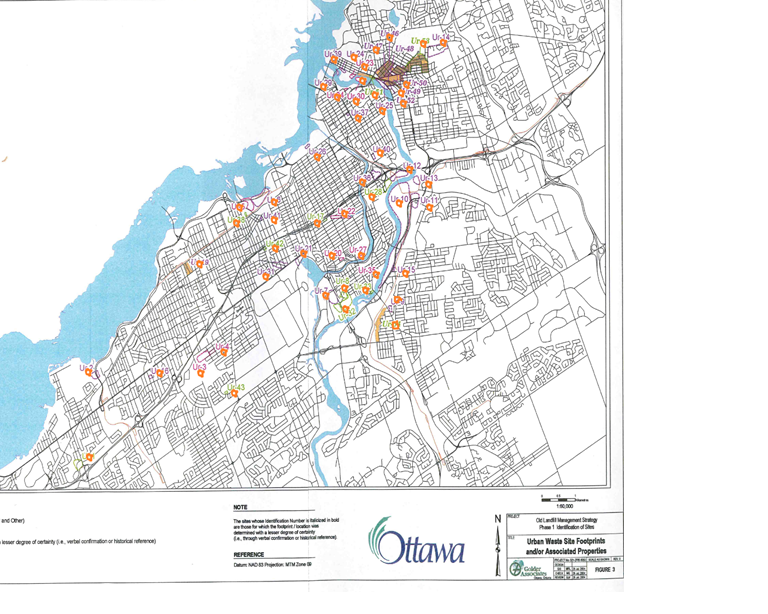

As well, no thought was given to integrating transit service, according to Ramsay. Some transitway stations were built in the wrong locations, from an intermodal point of view. Greenboro Station in Ottawa South was built 300 metres from the rail intersection. Some transitway segments — such as the southeastern stretch linking Hurdman Station and Hunt Club Road — are built beside rail lines, a colossal duplication of effort and waste of public funds, according to many LRT proponents.

The 8.2-kilometre Hurdman-Hunt Club link cost $182 million, with the 1.8-kilometre segment running from the Riverside Hospital to Billings Bridge Plaza Shopping Centre accounting for $65 million of this cost (or more than $30 million per kilometre).

"We're up against a lack of vision as to rail's potential benefits for the region;' said David Jeanes, manager of international marketing with Nortel, and treasurer of Transport 2000 Canada, a volunteer advocacy group that promotes public transportation. (Jeanes stressed that his views were those of Transport 2000, and not Nortel's).

"Canada is the only developed country that does not have rail lines connecting its airports to its downtowns," Jeanes noted. And Ottawa is the only city in the million-plus range in Canada that does not have rail transit. Other cities — even smaller ones — have reused existing rail lines to complement their bus systems, but the concept of intermodal travel seems to have passed us by here in Ottawa. There are no links between the bus and train stations and the airport. All three terminals are far removed from each other and inconveniently located for the traveller. The transitway/train station hookup is the single example in this region of enlightened, integrated transportation planning, and even this effort was botched by not including a walkway over to the JetForm ballpark!'

Jeanes would also like to see a demonstration project moved up to 1998. "There is a real danger that, even on our current schedule of launching a trial run in the year 2000, some of the regional rail infra-structure may disappear, and there may not be enough track on which to build a light rail transit system."

Jeanes believes that a six-month trial run along the 6.5 kilometre CP Rail corridor would cost about $10 million."It would be very low-cost. All the facilities are in place except for the station platforms, pathways and steps. Temporary structures could be built for use during the test phase."

Michel de Bellefeuille, manager of commuter systems at CP Rail in Montreal, agrees that possible abandonment of the line — known as the Elwood subdivision — could jeopardize LRT in the National Capital Region.

The St. Lawrence & Hudson Railway Company — the CP Rail subsidiary— owns and manages all of CP Rail's tracks east of Chicago, including the Elwood subdivision.

"We have been mandated to generate new business, increase the use of the line (which is only used to haul freight twice a night), and promote LRT for Ottawa," de Bellefeuille said. "Two years ago, CP Rail's eastern network was losing $60 million a year. In 1996, the St. Lawrence & Hudson Railway generated a profit of about $35 mil-lion. This is better, but still not a viable return on our investment. We must increase our annual profits by at least another $40 million. This means we may have to abandon rail lines, or sell others to short-line operators, in order to reduce our costs.

"We are still very interested in developing the line for commuter rail service, but we can't sit on these expensive assets much longer, waiting for regional government to make a decision. We would like to see the trial run carried out in 1998, and not in the year 2000. We have very high fixed costs for maintaining our tracks and other infrastructure. To amortize these costs, we need a higher volume of traffic. We have to divest ourselves of the line if it doesn't become more profitable!'

So far, the region isn't being swayed by such arguments.

Explained Harry Beere, RMOC's manager of transportation policy: "The region must negotiate separate deals with CN and CP, and this will take time. We must also meet federal safety standards. Basically, we're putting a streetcar into a freight train environment, although we don't anticipate any problems because of the light usage."

The Transportation Master Plan, prepared for the region by Dillon Consulting Limited, recommended a pilot study in the year 2006 but, after vociferous protests from rail enthusiasts, the start date was moved ahead to 2000.

"We'll do all we can to meet this deadline, but regional council must come through with money and we still don't know the cost of the trial run," Beere said. "We're looking for technology that will allow us to avoid paying high capital costs for building transit infrastructure.

Diesel light rail emerges as the most appropriate technology, since it won't require expensive electrification of the line. However, the final equipment selection has yet to be made. And we must still identify where the pilot study will take place?"

Beere said that exploratory discussions with the rail companies are now underway. The earlier interprovincial LRT proposal was viewed with trepidation by regional transit commissioners, as it would have meant direct competition for OC Transpo.

"That proposal was very much competitive rather than complementary to our rapid transit system, and we would have lost passengers on OC Transpo," Beere said. "What we now see in the official plan is a complementary role for rail. We can use the transitway service so passengers can transfer to a frequent two-way rail service. The LRT would carry commuters to their workplaces in areas not now adequately served by buses, thereby creating a new ridership. The new LRT concept relies on the existing transitway network to bring passengers to the rail lines. It also diverts some of the commuter traffic away from downtown. Too many buses now pass through the central business district?"

Beere noted that the primary transit service in Ottawa-Carleton will continue to be bus-based, and that this is reflected in the official plan. "We opted for incremental extension of transitways into suburban areas, and also identified the potential to introduce lower-cost transit measures and gradually upgrade to full, grade-separated busways. Paved, bus-only shoulder lanes along the Queensway are one example of a less expensive, incremental step we can take. We will gradually find a balance of having an effective transit system while deferring costs as far as possible into the future."

Beere said that the transitway was designed with eventual conversion to rail transit in mind. "We are designing for a broad spectrum of rail transit technologies. Certain segments of the transitway could eventually be shared by buses and LRT vehicles?'

He observed that "rail transit advocates say these rail lines are underused resources, but the adage 'build it and they will come' doesn't necessarily apply here. There is nothing to demonstrate that rail has any inherent attractiveness that would drive transit shares up compared to buses, although that is the perception. Busways are lower-cost and more flexible, and seem to generate more ridership, which also goes against the conventional wisdom?"

Beere noted that OC Transpo is leaps and bounds ahead of any transit system in North America in terms of ridership for a city this size. "We dwarf other cities of similar size in level of transit use, including cities with LRT systems such as Calgary and Edmonton." (OC Transpo's average weekday ridership is about 265,000 trips).

Beere attributes OC Transpo's decline in ridership to demo-graphics. The proportion of habitual transit users in the highest age group (15 to 25) declined by 50 per cent in the past decade. The economic downturn didn't help, either. However, ridership has plateaued, turned the corner and started to rise again, Beere noted.

As for a rail line sell-off, Beere isn't overly concerned. "We will deal with whoever is the owner and operator of that line, with a view to coming up with a mutually-satisfactory arrangement?' The RMOC also has a policy of acquiring any rail lines that are abandoned and not taken over by higher levels of government, with a view to preserving them for future transportation or other public use.

Beere said the RMOC will insist that any LRT system be part of an integrated transit network, rather than a stand-alone, separate-fare system. "It will have to be an integral part of OC Transpo's operation, although this doesn't necessarily mean it will be managed by OC Transpo. It might make more sense for the rail companies to handle the pilot study and operate the lines, but we'll just have to wait and see."

CN Rail is also adopting a 'wait-and-see' attitude, although it still favours LRT service on its 33-kilometre east-west corridor linking Ottawa Train Station and Kanata's high-tech centre.

"I think CN should proceed cautiously until we have a better idea of what the region wants," said Terry O'Brien, national manager in charge of passenger rail at CN Rail in Montreal.

"We'd like to see the trial run date moved up to 1998. Our interest in the project would be stronger if the region were to commit itself to an earlier start date for a test run.

"We've had preliminary discussions but we still don't know what the region wants. Is it considering an integrated CN-CP light rail network? I can tell you that CN will not operate a passenger rail service in Ottawa-Carleton. We'll supply the rail, but another party will have to provide the service."

Although the east-west rail corridor is not for sale at the present time, CN would consider a serious offer from a short-line operator. O'Brien believes the demonstration project should be kept as simple as possible.

"Some Ottawa rail advocates say we could get a three-month test run going in no time for much less than $10 million," he observed. "If a manufacturer would be willing to test its equipment free of charge in a Canadian environment, that would certainly reduce costs. I don't think it would serve any useful purpose to build permanent facilities for a test run. Instead of building fancy stations with elevators and other accessories, the region should build cheap stations with plywood platforms, while meeting minimum safety requirements.

"Basically, we're asking: 'What does the region want?' Tell us so we understand what the game plan is and we can proceed from there," O'Brien summed up.

Another strong supporter of commuter rail in Ottawa-Carleton is John P. Braaksma, a transportation consultant and professor of civil engineering at Carleton University. Braaksma says the region's 'go slow' approach to light rail stems from a wrongheaded philosophy shared by regional planners and engineers.

"Their mindset is firmly entrenched in fifties and sixties-style auto-dominated thinking," Braaksma explained. "Despite their pious platitudes about encouraging greater use of public transit, they think nothing of spending huge sums of money on things like the West Hunt Club extension and the widening of the Dunbar Bridge (near Carleton University) to six lanes, with a view to building a downtown-bound expressway along Bronson Avenue."

Braaksma believes that the fundamental flaw in the region's latest official plan is that planners and politicians are still mired in automotive-oriented thinking and not embracing the concept of multimodalism, where several transport modes are seamlessly integrated, working together to move people smoothly and comfortably.

The transportation specialist noted that the current fiscal crunch will likely prove advantageous for those who have long promoted the less expensive commuter rail option. "We've reached the point where we can no longer afford to build more expressways," Braaksma observed. "We don't have the money or the land to waste. Yet OC Transpo is dead set against rail, fearing loss of farebox revenue, whereas all the research indicates that rail service would actually enhance bus usage. OC Transpo should embrace commuter rail as a partner, and not view it as a competitor."

Braaksma also favours an earlier trial run. "So far, regional government has only paid lip service to commuter rail. Let's see some action to test the concept's viability, preferably on the Lebreton-Carleton University segment, a short link that would be intensively used, especially by the student population. We could build temporary stations at Lebreton, Carling Avenue and the university. Ideally, the trial run should last a year, under all-season weather conditions. We would ensure good connections with OC Transpo, matching timetables and providing for a uniform fare. An unbiased evaluation would probably take another year, but if a commuter rail service were approved, we could have a system up and running within three to six months?'

A speedy and efficient LRT service would also solidify links between Ottawa's international airport, Kanata's high-tech park and Carleton University's research facilities, strengthening the region's overall economy, Braaksma said.

It appears that light rail advocates must remain patient for a few more years, perhaps over the life of the region's official plan (which extends to 2021). Ottawa, which once boasted a city-wide streetcar line running from Rockcliffe Park to Britannia Beach, and an extensive network of inner-city rail lines, will someday have its own 21st-century equivalent of a streetcar service, but it's going to be a slow train coming.