When the Montreal Road was Eastview’s main street

There is a tiny piece of France hidden away in Ottawa, in a part of town that was once on the outskirts of a town once known as Eastview. La Grotte de Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes is a holy enclave nestled among mature trees next to the church whose matron revealed healing waters to the faithful and the hopeless. The Eastview grotto originated in Cyrville and was moved closer to town about a hundred years ago. An actual spring was tucked into the rocks up until not that long ago. People still drop by to light candles and attend Mass outdoors in the Summer. A noble and glorious stone church built in 1877 burned down in 1973 and was replaced by a modern descendent, next to the once-rural cemetery where Sir Wilfrid Laurier is entombed. There is heritage to be found here.

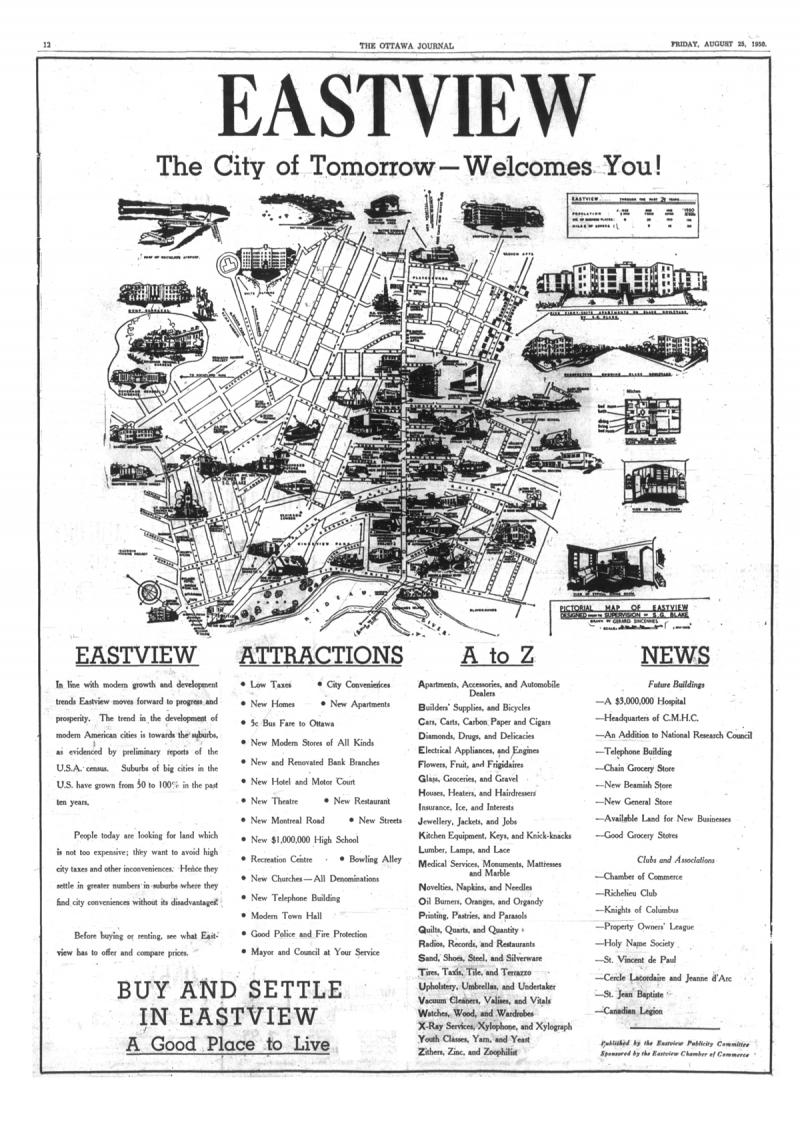

Eastview was an amalgamation of little villages east of the Rideau River in Gloucester Township along the King’s Road. Charles Cummings founded a settlement on an island just south of the fine old bridge that bears his name. An early map of Janeville, commonly referred to as Cummings’ Bridge, indicated a toll booth and some of the earliest streets. Montgomery was Victoria, the quirky Palace St. took a doglegged bend, and McArthur Road quickly trailed off into that family’s farm. Later additions like Bradley and Olmstead streets were named for other early families.

Janeville was bisected by an industrial rail corridor that was active until the 1960s when it made way for the Vanier Parkway that abruptly ends at New Edinburgh where NIMBY outcries were heeded.

The original town character can still be seen on along the Montreal Road where homemade houses hug the sidewalks and front porches are centres of neighbourly conversation. Streets named Carillon, Durocher or otherwise named for the communion of saints reflect what was a majority francophone population who settled here from eastern Ontario and the Québec side to work for such new employers as Laurier’s Ottawa Improvement Commission.

Like other minority language enclaves in Ottawa, Eastview was blue collar labour educated by Catholic schools. Ottawa, Ontario, and Canada generally were divided economically by language and denomination. One just had to locate the old Catholic churches in the city to identify the segregation. Eastview, Hintonburg, and Lowertown (also home to the oldest synagogue in town) versus the Uptown St. Andrew’s, Christ Church, and First Baptist of remnant British Upper Canada; St. Patrick’s on Lyon being the exception. I long recall unkind comments uttered down noses at those lower neighbourhoods by those who lived upwardly. They were not exactly fair characterisations.

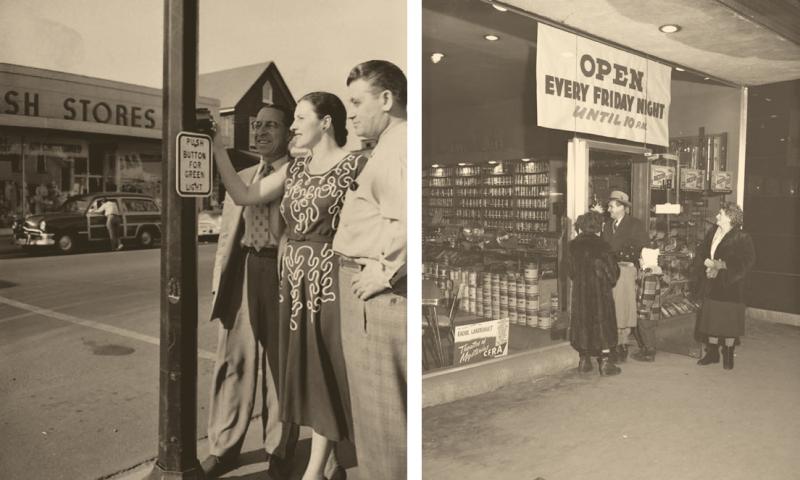

The Montreal Road was an authentic main street of a real community whose identity was still that of a town. Locals could find anything from fresh produce to jewellery stores, men’s and ladies fashions, and variety stores like R. A. Beamish and Woolworth’s. My Syrian family had a much-loved dry goods store, Laham’s, at the corner of Park Street. There were steak houses for date nights and family restaurants for Friday nights with the kids. Kids and schools and churches were everywhere. The Golden Rail at the Lafontaine Hotel was probably the best country and western bar in the Ottawa Valley. The Butler Motel’s lounge featured Dick Maloney and his heartfelt tribute to Frank Sinatra, and the Hotel Eastview was famous for its dining room. There was a police station in the middle of it all where my dad Oscar worked for 31 years, retiring as the deputy chief of the 45-man Vanier police force. There was one murder during his career; a Montréal mafia hit in a motel room.

Eastview had always been an autonomous municipality with a mayor and council, but the one square-mile city had become surrounded by Ottawa in the post-war boom. Farm land along McArthur Road was replaced by low-rise apartment buildings for families and new schools appeared. By the time Eastview had been renamed in honour of Gen. Georges Vanier in 1969, the state of things had begun to change due, according to my retail family, the opening of St. Laurent Shopping Centre.

A vital, vibrant community of families joined the exodus to suburbia in communities like Orléans, Rothwell Heights, and Blackburn Hamlet. Over time, Vanier became the antithesis of the modern suburb where sidewalks and corner stores are nowhere to be seen. The closest Starbucks or Bridgehead are found on the more tony north side of Beechwood Avenue, but you will find phone booths and laundromats, remnants of another urban era and signifiers of an economic ghetto.

I lived in the Glebe for twenty years prior to Bank Street’s transformation from a friendly main to a head-on collision with the Smart Centre™ known as Lansdowne ‘Park’. Rickety telephone poles remained in place due to cheapness or perhaps some clever nod to the bygone days of the local telegraph office. Sidewalks crowded by sandwich boards and families of cyclists riding where they shouldn’t are now further cluttered by preachy red things that command residents to this and that.

Montreal Road is about to undergo a similar renovation, and one wonders how it will revitalize a neighbourhood slated for an addiction mega-shelter whose indubitable home would be a motel in Westboro in a parallel universe. Vanier’s main street truly needs revitalization, and the potential is evident in what is already there.

Firstly, preserve the town character as has been done in neighbourhoods like Montreal’s Griffintown or Parc Ex. Don’t let developers shove slabs and boxes into it. The street configuration cannot accommodate density, nor are there significant properties available for conversion. If the proposal is to replace Eastview Shopping Centre with towers, then consider how increased density demands even more pedestrian-friendly retail. Rideau Street is rapidly transforming into a canyon, and while its proximity to the downtown core may make this reasonable, remember that Rideau Street used to be the finest shopping street in the city and home to local businesses including four family-owned department stores. It is now a name-brand street like any other in North America.

Secondly, embrace the fact that all four indispensible conditions for what Jane Jacobs referred to as “exuberant diversity” already exist in the fabric of Vanier: short blocks that encourage pedestrian exploration; street-level versus vertical density; a diversity of functions in which retail and residential closely intermingle, and; a mix of newer buildings with older ones that afford a range of rents to younger entrepreneurs. Imagine the funkiest mix of creative spaces and artists’ galleries in a part of town where world cuisine is already taking hold, not to mention the little-known designation of Little Nunavut.

Thirdly, if the mega-shelter is cast in stone, then re-instate a 24-hour neighbourhood police presence. My dad walked the overnight beat on the Montreal Road wearing two pairs of long johns in arctic temperatures. Police presence is today encapsulated in hi-tech supercars that only swoop into a scene when a call is made. The revitalization of a neighbourhood requires more than sewers, public art, memos from developers or a consultation process. It first and foremost requires recognizing what is already good about a part of town and not screwing it up.