At best, Minister of Health Mark Holland is Blatantly Ignorant. At worse, he is lying to Canadians with Diabetes

Canadian Government’s Universal Access to Diabetes Medications Falls Far Short.

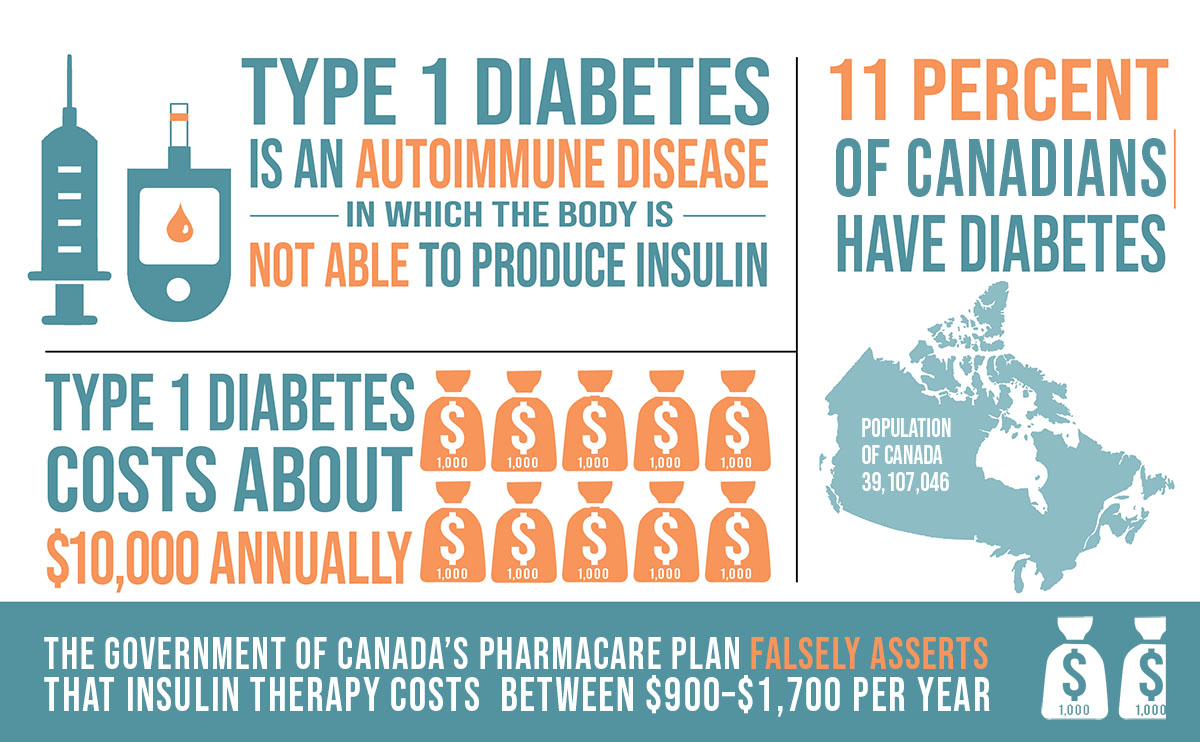

Type 1 diabetes, also commonly referred to as Juvenile Diabetes, is a disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks insulin-producing islet cells in the pancreas, halting insulin production. It can occur at any age, with no cure available. Managing the condition is lifelong and involves multiple daily insulin injections, repeatedly testing blood glucose levels, and carefully counting carbohydrates. It’s a challenging and constant responsibility further complicated by stress, illness and more.

For Type 2 diabetics, insulin production gradually decreases, and the body develops resistance to insulin’s effects. People with Type 2 diabetes may also need insulin if their condition worsens to the point where manual injections are necessary, though generally, Type 2 diabetes tends to be less severe than Type 1.

When Dr. Frederick Banting first tested insulin on humans in 1922, it was hailed as a modern medical miracle. He transformed a fatal illness where patients die from ketoacidosis into a treatable disease. Banting sold the patent symbolically for $1, hoping insulin would be freely available to all people with diabetes.

In the hundred years since insulin’s development, many innovations have emerged, from blood testing strips to continuous blood sugar sensors and insulin pumps that emulate the pancreas. All these technologies should be seen for what they are: treatments to manage a life-threatening, life-long illness.

Managing diabetes without insurance in Canada is a financial strain that is hard to grasp for those unfamiliar with the costs.

Insulin prices vary widely depending on the brand and purpose. Fast-acting insulins for meals differ from longer-acting insulins designed to last all day. For both types, a month’s supply ranges from $250–$350 and a box of test strips, essential for frequent blood glucose testing to avoid dangerous highs or lows, costs between $80 and $100.

As a Type 1 diabetic, I use one box of strips per week. There is also the added cost of needles, which can range from $500 to $1,000 per year, depending on whether needles are reused—a practice that healthcare professionals do not recommend, yet one that many uninsured people adopt to cut expenses. Insulin usage varies among people with diabetes due to individual factors like hormone balances, lifestyle, and body size, which affect insulin needs. The annual cost to live with Type 1 diabetes is roughly $10,000.

But insulin, test strips, and needles are only the basics. Adding a continuous blood sugar sensor, which transmits readings to a phone, costs approximately $100 per unit, lasting ten days, plus $100 for a transmitter that works for three months, with an annual average of $3,900. Using an insulin pump, depending on the model, costs around $7,000 but can last several years.

In 2017, Type 1 diabetics came close to suffering a serious financial blow when the Liberal government tried to roll back Disability Tax Credits, which is a mere $1500 annually. They argued that advances in medical technology had shifted enough that it was no longer necessary. The CRA also stated that diabetics had to spend 14 hours a week managing the disease (you manage it all day, every day for the rest of your life) and noted: “(The) CRA maintains that many activities needed to manage the disease – such meal planning – do not fall under the category of life-sustaining therapies.”

The statement demonstrates how completely out of touch they are. Failing to plan for a meal with diabetes and taking the wrong dose of insulin can be fatal. Perhaps more interesting is that at a time when they were looking to punish Canadians with diabetes financially, the Globe and Mail and Global News reported that supply costs for diabetics in a year were upwards of $15,000 per annum.

Despite lingering scepticism from their previous effort to roll back benefits, when the federal government announced a diabetes pharmacare plan, it was finally a reason to feel hopeful. The idea of paying out-of-pocket for medications to stay alive daily, especially in the country where insulin was discovered and symbolically given to humanity by its inventor, is frustrating for many with Type 1 diabetes.

For us, healthcare has never felt universal. Paying to survive hardly aligns with the ideals of socialized medicine.

Curious about the National Diabetes Care Plan, the so-called Universal Access to Diabetes Medications and Diabetes Device Fund for Devices and Supplies, I visited the Canadian government’s website, where my optimism faded quickly.

The website lists insulin therapy costs at “$900–$1,700 per year, depending on the type and dosage”; a wildly inaccurate figure. Insulin has never been that affordable.

With this false estimate as a basis, the government lists the brands covered by the Pharmacare plan. Unfortunately, none of the common insulins my doctors prescribed—Fiasp, NovoRapid, or Lantus—are included. These brands are often out of stock at pharmacies in Ontario due to high demand.

A Type 1 diabetic cannot simply switch insulin brands. Such a change, without guidance from a medical specialist, can have life-or-death consequences, and with the healthcare crisis, there are long wait times to access an appointment with a diabetes doctor. If the commonly used insulins aren’t covered, and if a person with type 1 diabetes does decide to change brands, they may have to wait months to see a doctor to make the switch, and if a switch is possible, then it might take months to adjust to using the covered insulins.

It appears that the civil servants who drafted this plan conducted only minimal research, possibly failing to understand the significant difference between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes and failing to consult medical professionals on actual costs or commonly prescribed insulins.

The cynic in me wonders if the insulin on the government’s list might be there simply for its lower cost rather than commonality, enabling the pharmacare program to cut expenses.

Moreover, test strips are omitted from this plan despite their essential role in diabetes management. Annually, they cost more than twice as much as insulin and are critical to effective diabetes management.

A person with diabetes who doesn’t know their blood sugar level can’t adjust insulin doses, risking dangerous highs or lows and even diabetic ketoacidosis. This condition causes you to feel quite sick.

Failing to include these necessary supplies shows that the government’s plan lacks genuine commitment to comprehensive diabetes care, not to mention that needles, essential to inject insulin, aren’t covered either.

As a Type 1 diabetic, I am frustrated that the government is using a condition that causes Canadians physical and financial hardship to make a hollow gesture under the guise of a national pharmacare plan.

The Canadian government’s plan is essentially a feeble attempt at virtue-signalling that will have little impact on the care of the 285,000 Canadians living with type 1 diabetes. But, given that this same government offered a Canadian Forces veteran medical assistance in dying (MAID) as a substitute for a requested chair lift, it’s perhaps unsurprising.

The Liberal government’s Pharmacare Act falls far short of being a genuine diabetes care bill. I’m confident Dr. Frederick Banting would agree.

Don’t believe Mark Holland when he says he’s covering the cost of medical supplies for Canadians living with diabetes. He is either ignorant of his own legislation, or he knows. I’m not sure which is worse when it comes to a life-or-death treatment like insulin therapy.

HEADER IMAGE: The federal Health Minister, Mark Holland, is shown next to someone administering insulin. A century ago, being diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes was tantamount to a death sentence. Before Frederick Banting’s discovery, those newly diagnosed could expect to live only a few days or weeks. (PHOTO: iStock)