The Uncertain Future: France’s Socialist Resurgence

All is not well in Europe. The European Union (EU) in general and the Eurozone financial union in particular are in a precarious position. Crushing debts and deficits as well as unsustainably expensive social welfare programs — not to mention unemployment rates in excess of 20% in certain EU countries — have turned what many academics call “Eurosclerosis” (the lack of economic growth and consistently high unemployment rates) into reality for much of Western Europe. International institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have contributed billions of euros (the EU’s international currency) to stabilize the toxic economies of nations like Greece and Spain in an attempt to prevent them from defaulting on their debts. Should default occur, it could trigger a collapse in the value of the euro, a move which would likely lead to the demise of the Eurozone and possibly the EU as a whole. Such a monumental economic and political collapse would unquestionably plunge the highly interconnected global economy into a severe recession at best and a global depression at worst. But, all of this is old news.

However, the surprising results from both the French and Greek national elections last week have the potential to exacerbate political differences and to further polarize both the European public and European policymakers. At issue is the difficult, but necessary, task of writing and implementing policies that would reduce member states’ deficits as well as government expenditures, all the while spurring growth and reducing unemployment throughout the EU. It is no small task to do so and still remain palatable to European voters. It would be difficult in any country but it is far more so in countries like Greece and Spain which, for all intents and purposes, are currently in depression and not recession. This act of political tightrope walking will be much more challenging in the near future due to the fact that both the Eurozone and EU may well be placed on life support in coming months. While France may not suffer from the same depression-level unemployment rates common in Greece, nor does its balance sheet contain as many toxic assets, France faces a number of challenges which, if not defused, could harm the Eurozone, the EU and the interconnected global economy even more than a Greek default.

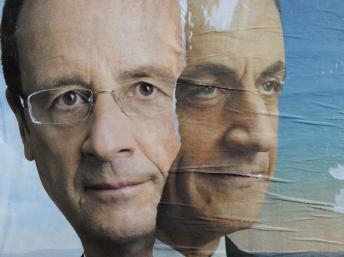

Incumbent politicians often share the praise and the blame for their nation’s economic performance. Given the EU’s lack of economic performance, it is not surprising that any incumbent politician seeking re-election in the EU would face public opposition. Last Sunday, French President Nicolas Sarkozy and his centre-right Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) Party lost their re-election bid by a narrow, but still significant, margin of 48% to 51% in favor of Sarkozy’s Socialist challenger Francois Hollande. In the past, the French Socialist Party (PS), now led by Hollande, has only elected one man to the highest office of government. Thirty-one years ago, in 1981, the Socialist Party’s Francois Mitterrand was elected President of France. He remained in power throughout much of the 1980s and served a second term in the first half of the 1990s.

Generally speaking, financial markets did not react positively to Mitterrand and the Socialists’ tenure. There is a likelihood that markets will again react negatively to a France led by a Socialist government, but today the consequences could be more serious than when Mitterrand was in power. Francois Hollande has taken an anti-austerity stance which resonated with the large population of French unemployed and also with the public sector workers who would likely bear the brunt of any austerity program intended to stabilize the Eurozone countries. Doubtless, these positions played a crucial role in the defeat of Nicolas Sarkozy, a man who led a party which advocated the merits of austerity and whose flamboyant personality has taken its toll on French voters’ good will. Hollande has advocated the need for protectionism, has called for the implementation of a 75% income tax on wealthy French individuals (which would strangle growth and innovation) and has rejected the austerity measures required to keep France’s fiscal house in order. Hollande says he prefers to have the French economy “grow” its way out of recession and that he is not averse to using quantitative easing to spur that growth.

At best, Hollande’s agenda will likely create an unpleasant environment in which the 27 member states will seek to solve their debt and unemployment problems, a task made more difficult since his views directly challenge those of German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Merkel leads the EU’s strongest, most economically solvent country and has stressed the importance of balancing the EU’s books and of reducing deficit and debt by way of austerity measures. Negotiating and implementing successful policies could be more difficult when the EU’s most powerful country (Germany) and second most powerful country (France) have two conflicting ideologies separating them on the important issue of countering the ongoing European economic crisis. At worst, this conflict could make any further coherent economic policy-making an impossibility, thereby derailing future hope for the stabilization of the EU’s economy and the lifespan of the euro as a viable currency.

France and Germany, along with the other 25 nations in the EU, would suffer greatly should this occur. This scenario would deal the global economy a crippling blow that could suddenly halt the current anemic recovery in the majority of the world’s developed economies. Unlike Greece, France is well-integrated into the larger European marketplace in terms of the business it conducts beyond its borders. For instance, French companies operating outside of France, but within the EU, provide some 4.5 million jobs in a cross-section of virtually all forms of business. Furthermore, unlike Greece, these 4.5 million satellite French workers create products and services which, when combined, account for almost one fifth of all European investments in terms of monetary value.

To raise the stakes even further, France’s financial system provides significant capital and loans to other EU countries like Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Italy — countries which are burning through money as if there were no tomorrow. Some of those countries may well default on their debt no matter how much money the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or Germany may reluctantly provide to shore up their hemorrhaging economies. Should President Hollande obstinately pursue his hard-line, hands-off position against austerity which runs counter to that advocated by both Germany and the IMF, France and its creditor nations could fall into the abyss.