Kafka Choreographers

I was chatting with two women over dinner a few weeks ago when one asked me; “How do you go about choreographing a dance?”

It’s a tricky question to answer without sounding like an alien or an arts snob.

I hesitated then replied. “I see ideas, do lots of mulling, visualize an image or movement idea, go for funding, then enter the studio to choreograph.”

Over the years I have had numerous discussions with my dance-making colleagues, sometimes in hallways at rehearsal studios, sometimes during intermissions at shows or over beers after our version of a long day at the office. Tellingly, we tend to share stories about the commerce of running a company and/or getting a dance project off the ground as often as sharing enlightened revelations about the mysteries and challenges of the artistic process.

Choreographers (independents or artistic directors of companies) inhabit a nightmarish world of funders and festivals and producers and presenters and scheduling conflicts and grant writing and meetings and small time politics. Even Kafka would be dismayed by the trials and tribulations we endure in order to move ahead with our mission, which is to make good, if not great, dance.

“I have never met a creator who takes for granted the fact that we receive some of our support from taxpayers’ dollars. However, we represent a miniscule percentage of the overall money pot. Even conservative governments acknowledge that the arts are a huge employment sector. Some even admit that the arts are important to the advancement and spirit of a nation, and volunteerism is the backbone to dance-making in this country, especially by the choreographers themselves.

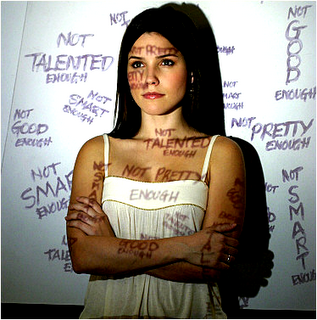

One of the Herculean tasks all creators must embrace is that of writing grants in order to be able to go into the studio to create a piece. We have to write intelligently, descriptively, artistically, in excruciating detail about a notion, a feeling, a concept.

Choreographers begin by sitting week after week in front of the computer composing a minor tome about our “amazing new dance creation”. This masterful bit of writing will then be judged by dance officers and juries who rifle through pages and pages filled with wordy descriptions and budgets and cast lists and mission statements and performance commitments. (Remember it’s one of hundreds they have to plow through.)

Then we wait for months to be told whether we received the funding. Meanwhile we are to be informing all of the future project’s collaborators about the whens, wheres, hows of the rehearsals and designs and performance dates – essentially all the little details that everyone needs to plan for and think about for financial and artistic and scheduling reasons.

Then, finally, we receive the money required to create the work. However we only get 60% what is needed so it’s back to the drawing board; i.e. reducing the number of dancers, cutting out costume design, letting go of the composer, forgoing that all-important set piece, it could be one or all of the above.

Furthermore, one cannot create a dance without a space to rehearse in. There are numerous stories out there about not finding available rehearsal space 6 weeks before the upcoming performance or losing a dancer because she/he has had to commit to another project. (This is because we cannot sign contracts with anyone until we have all the funding in place).

Finally, if you pro-rated the hours and days and months before we even step foot into the studio to begin the fun part of the work, being paid minimum wage would feel like a windfall.

However, having detailed the above dirty laundry list, very few choreographers experience regret or choose to give up. We tend to forgive and forget the pervious months of craziness, or at least until the next new project comes knocking at our door. Because once we get into the studio, we are working with quality artists who help us transform bureaucratic drudgery into the magic and craft of artistic creation.

It seems that Kafka is alive and well in the castle of choreographers working across this country. Little did he know he was writing about dance creators everywhere, past, present and well into the future.