30 years since oversight bodies, police accountability remains an issue

By Susan Rabichuk and Lisa Deveau

We have been indoctrinated not to question the police. Adequate police oversight and accountability is long overdue.

Officers swear an Oath to uphold fundamental human rights and equal respect, but what happens when officers, including the chief, abuse their power, or, in the case of the Freedom Convoy, fail to act in the best interests of all, seemingly aligning with the radical right? Where do those who have been wronged by the police turn to for justice and peace when the police are the gatekeepers of the law?

The Freedom Convoy has simply highlighted what has been playing out for years, policing as an institution upholds and reinforces capitalist, white supremacist, cisheteropatriarchy that is embodied in police culture.

Approximately 30 years ago, Ontario established ‘independent’ police oversight bodies (Special Investigation Unit and Office of the Police Complaints Commissioner) in response to protests for the death of a young black man at the hands of police. Very limited, yet crucial, evaluations of these oversight bodies found that an overwhelming number of Ontarians [70%] felt that “non-police people” should carryout investigations involving officer misconduct; 73% did not think it was a good idea that police make the first decision in substantiating a complaint; and only 14% of all citizens who completed the entire complaint process felt their complaint received a fair investigation.

It is apparent very little has changed since the creation of supposedly “independent” oversight bodies that are intertwined with the police boards, Chiefs, and police services, often staffed by former officers. The illusion of accountability is merely smoke and mirrors.

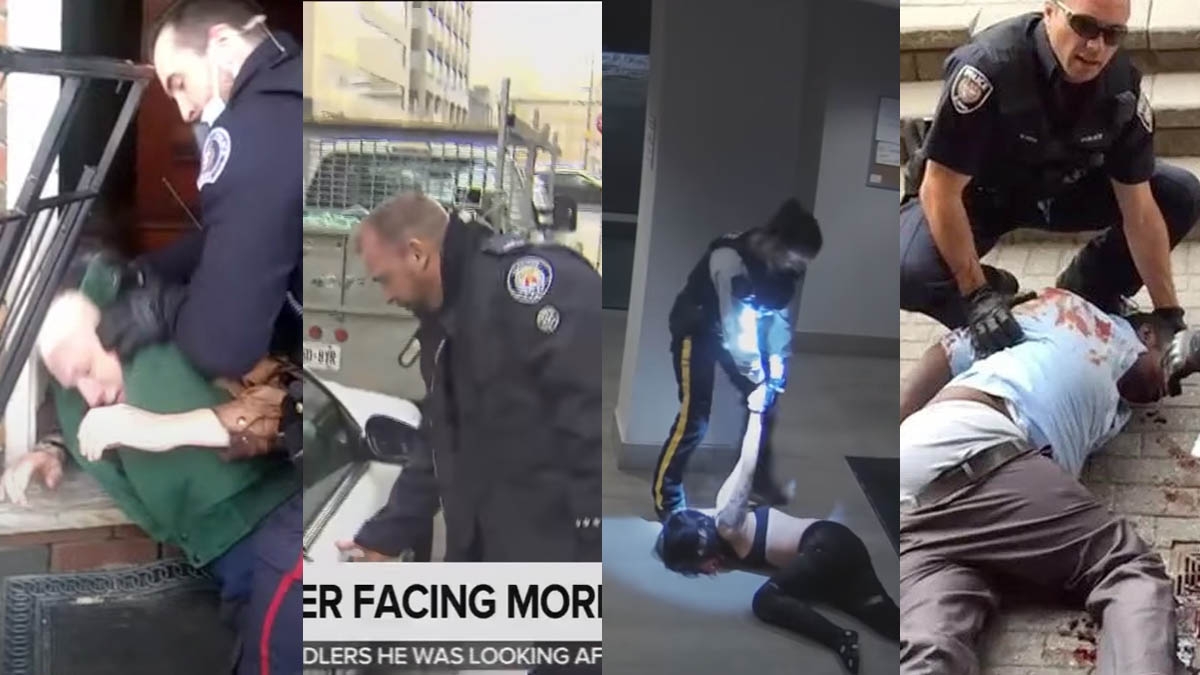

While the majority of officers are well intended people who strive to make positive contributions, the institution within which they work creates an environment that condones and maintains toxic police culture. The officers that engage in excessive use of force, racially profiling citizens, and sexually assaulting/harassing their colleagues and members of the public have been allowed to remain police officers, often climbing the ranks to executive levels. A key driver of their success has been the lack of accountability/discipline from within.

In Ontario, there are two avenues to investigate officer misconduct toward civilians: Office of the Independent Police Review Director (OIPRD) and Special Investigations Unit (SIU). The SIU, an independent agency, investigates police-involved incidents resulting in the death or serious injury of a civilian and sexual assault allegations. Police services are obligated to report death or serious injury of a civilian by an officer to the SIU who then conducts an investigation and has the power to criminally charge officers.

However, who is tracking police services to ensure they are adequately reporting excessive use of force? The second option, if misconduct does not fall within the SIU mandate, is the OIPRD, which issues charges under the Police Services Act.

Any member of the public and Chief can make a complaint about an officer to the OIPRD; officers are prohibited from making a complaint against a colleague including the Chief (58(1)). The OIPRD can either investigate the complaint or assign the investigation to the Chief (61(5)a). The Chief not only completes the investigation, but determines the disciplinary measures, despite this obvious conflict of interest (66(1-9). The Chief can choose one of three options: no action (unsubstantiated complaint), informal discipline, or a hearing (formal discipline), decisions are to be forwarded and reviewed by the OIPRD. An unsubstantiated complaint stops the investigation. Informal discipline (of which no clear definition is offered), proposed by the Chief, needs to be agreed upon by the complainant and the receiving officer.

The only time an officer can receive what appears to be real consequences is when the investigation goes to a hearing. If the hearing concludes that misconduct has been “proven on a clear and convincing evidence,” the Chief can take several disciplinary measures, including dismissal (84-1; 85(1)). Yet, dismissal is rare. Following dismissal or resignation, officers must wait a minimum of 5 years before being employed by another police force according to the PSA (85(10)).

But what happens when officers commit criminal offences that have been treated as workplace transgressions under the PSA? What if they align with the radical right and offer support (both overtly and covertly), such has been the case with the Freedom Convoy? And what about officers who are at the center of informal disciplinary measures or non-disclosure agreements connected to sexual harassment and assault? We will never know the extent of the behaviours because they are kept hidden under these veils.

The current system is not working. It is failing victims, both citizen and police victims. When are police going to be held accountable by a completely independent body who do not hire former police officers to investigate current police officers?

The OIPRD specifies that “current police officers” cannot be investigators. But what about former officers as many SIU investigators are former officers? When is there going to be legislation that prohibits Police Chiefs from investigating their own employees? Are citizens to believe agencies cannot find qualified candidates outside of the policing profession to conduct investigations?

We strongly believe there are capable ethical investigators who can conduct investigations independent of police organizations. Whistleblowers, civilian victims, and those advocating for racialized and marginalized communities need to come together in our common goal of achieving police accountability and force change on the system. Chiefs hold a substantial amount of power and the Police Services Board, who elect them, and are afforded the authority to discipline them through the PSA. It is time for real change.

Susan Rabichuk is a doctorial student in the Community Health Sciences Department, University of Manitoba. She holds a master’s degree in social work and is a former police officer.

Lisa Deveau is a former officer for the Ottawa Police Service. She holds a masters degree in social work.