Below is an excerpt from January: A Woman Judge’s Season of Disillusion by Marie Corbett. January is the story of Corbett’s personal and professional lives becoming painfully entangled. Facing a number of important trials while trying to comfort an ailing friend, Corbett must find an answer to questions she’d never asked before.

By nine o’clock, I was in my chambers and dressing for court. I threaded the watchband through Anne’s ring and tucked both of them in my vest pocket, so I would have them close and couldn’t misplace them. As I fastened the tabs around my neck, I couldn’t get my head around it. Why am I not at Anne’s side? She was my friend, I loved her, and nobody else was there. It was obvious that I should take time off to be with a dying friend. Why didn’t I call the Regional Senior Justice and say, “I have other priorities. I’m taking a leave of absence for a while”?

When I’d told Anne earlier that I would be willing to accompany her to California to seek treatment, my commitment had been genuine. It wasn’t merely a dramatic response engendered by a dramatic situation. What was so important now about my work? Nothing in my life as a judge couldn’t be postponed. The muddle of the trial with the tattooed bikers could start again after two days of evidence. A few other cases would have to be rescheduled, but trials are routinely rescheduled for many reasons. In my judicial career, I’d missed only five days of work, and those were in the first three months, when I’d foolishly tried out my sons’ skateboard and fractured my elbow. The truth is that accused persons aren’t anxious to get to trial, and delays work in their favour. Witnesses move away, memories become dimmer. And then there is the legal dance of seeking adjournments with an unexpressed hope of getting the charge dismissed because of delay in bringing the case to trial.

Devoted to my work, I took pride in being a thorough, fair, and competent judge. Even as opportunities had arisen to visit Anne, I’d felt guilty leaving my chambers without offering to do other work, as if my professional life was more worthwhile than my personal one. Although I was trapped in the daily exigencies of my workplace and my work, I felt it more important to be with Anne as she struggled to stay alive.

I saw that imbalance, yet I couldn’t act on it. My lifelong commitment to work and to doing that work well was ingrained, along with some mantras: Get an education; get a job; be successful. In law school, I had added the goals of contributing to social and legal change. I was dutiful to family, career, community. Never could I remember anyone saying that happiness was a worthwhile goal. If they did, it passed me by. Now, having achieved secular success and respectability, I was no longer sure of their value. I was no longer living as I wanted to live.

Still, I entered the courtroom exactly at ten o’clock. I was an on-time judge.

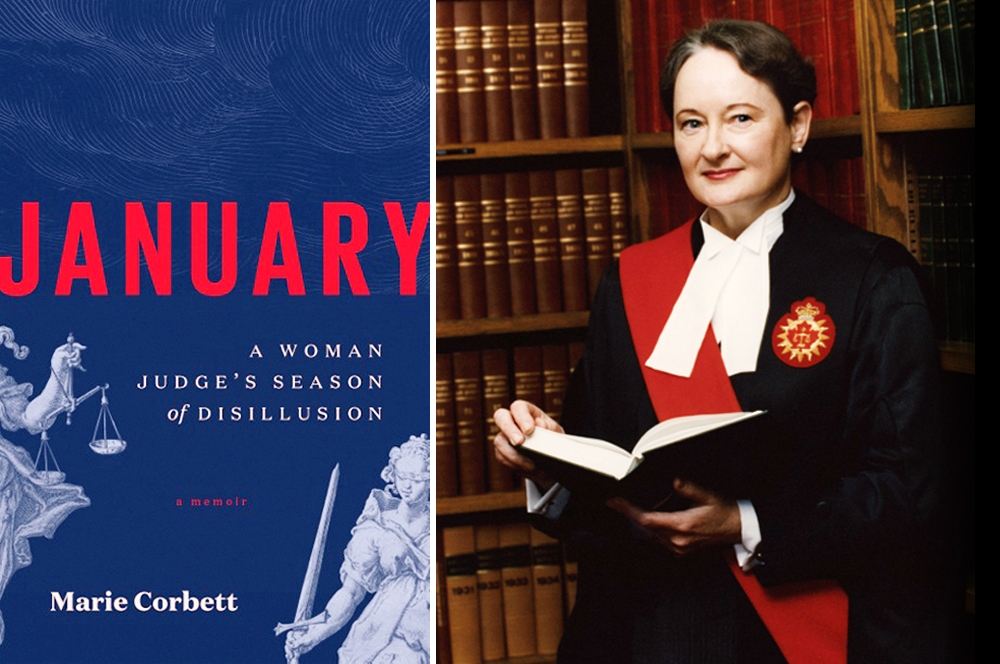

The Hon. Marie Corbett, Q.C., is a retired superior court trial judge who presided in Toronto for 14 years. A dedicated crusader for social justice in Canada, Corbett was a founding member of and first woman President of the Canadian Environmental Law Association. As a member of the first Ontario Status of Women Council, she organized the first family law conference pressing for women’s rights in marriage. Her honours include Queen’s Counsel and Women of Distinction Special Award from the YWCA.