Located in the South West of Astana, in the village of Akmol, Kazakhstan, the Alzhir Memorial Museum was opened by on May 31, 2007 by President Nazarbayev to honour the suffering and death of the tens of thousands of victims who suffered at this Stalinist era women’s gulag. As a newly-independent nation Kazakhstan has worked hard to acknowledge what happened on its soil in the name of the Soviet Union and to keep the memory alive, so that it cannot happen again. The museum offers a glimpse of the injustices and hardships faced by women sentenced to prison during the Soviet era.

From 1937 to 1953, such Soviet forced labor camp operated to imprison female political, intellectual, doctors and artist who deemed traitors. It was one of the most notorious camps in central Kazakhstan, where hundreds of thousands of women, along with their children, were sent to end their lives in the most pitiful way. Alzhir was the largest women’s camp in the Soviet Union where wives, mothers, daughters or sisters were considered as guilty as their husbands by association.

In the Stalinist period, especially in the period of the purges, there were large numbers of such camps, for political prisoners and their family members. They were convicted on the grounds of suspicion of disloyalty, as well as for returned War World Second prisoners of war. Needless to say that the capture by the enemy was regarded as a punishable crime, and for large numbers of Poles deported after the joint Nazi-Soviet invasion of 1939.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the camp was closed and female prisoners and their children began to tell their experiences at Alzhir. Women were forced to build their own barracks from mud bricks in which held about 200 or 300 women. The forced labor the women had to perform consisted of sewing army uniforms, raising livestock, other agricultural tasks and even construction work.

Food rations were meagre and winters were horrific, given the totally inadequate protection from the cold. The hardest was the fact that they had been separated from their loved ones and their children. Young children of so-called "betrayers of the homeland" were frequently taken from their mothers for good and given away for adoption. Despite this scenario, commanders and guards were not as brutal and heartless as necessarily people could consider insofar as they knew that women prisoners were innocents.

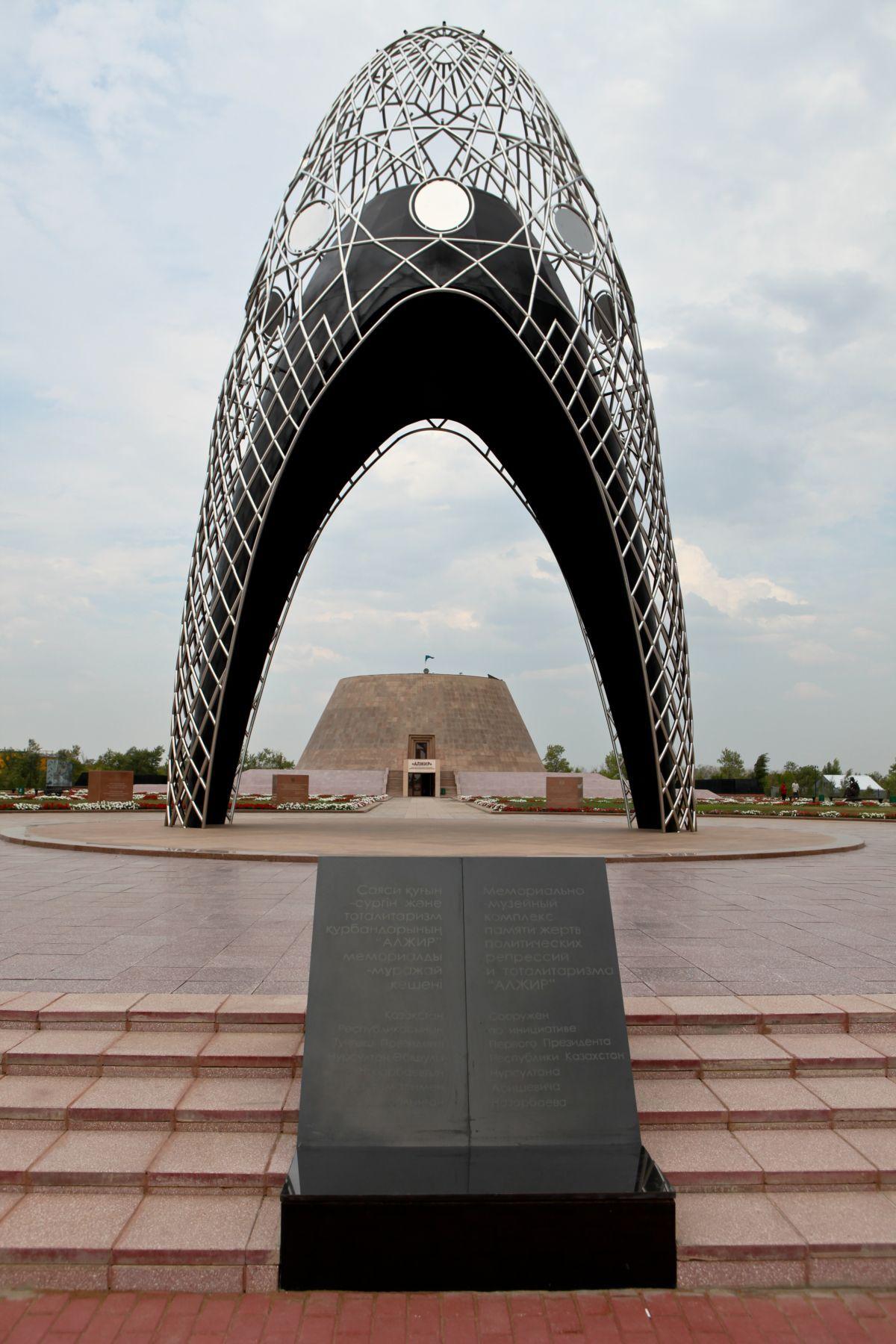

Among the representative things to see, the museum has an Arch of Sorrow designed in the shape of a traditional Kazakh wedding head dress, and beyond it memorial plaques for victims of from individual Soviet nationalities. One male and one female symbolize the two extremes of the gulag experience: a male looks down, broken in despair, and a female stares into the future, seeing life beyond current suffering. In the museum there is also a black marble walls inscribed with the names of thousands of prisoners: some of them were loyal Communist Party members but most of them were prisoners of humbler backgrounds. Some of them died there, some of them survived.