Back to the Future: The Fall and Possible Rise of the Liberal Party of Canada

By Dan Donovan and Simon Vodrey

It has come down to this. On Election Night, May 2011, the once great Liberal Party of Canada was pummeled. It seemed unbelievable that the “Natural Governing Party of Canada” had fallen from grace with a loud thud, placing third in the polls, unable to muster enough support to beat the New Democratic Party (NDP). The NDP had strategically focused its campaign on its popular leader, Jack Layton. Layton had just fought off a serious battle with cancer and, without missing a step, jumped into the election with renewed vigour. People responded to his positive attitude and populist appeal.

Meanwhile, the book-smart Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff seemed to be lacking political smarts. This became painfully obvious during the nationally-televised leaders’ debates. Layton nailed Ignatieff, pointing out that he had missed more votes in the House of Commons than any other sitting member. “Canadians know that if you don’t show up for work, you don’t get a promotion.” Ignatieff appeared stunned and said nothing. It was one of the biggest “deer in the headlights” moments in Canadian political history. To be fair, Ignatieff had only missed those votes because he had been spending most of his time outside of Ottawa visiting ridings and smaller towns, getting feedback from Canadians and listening to peoples’ concerns. The problem was that when Layton hit him with the unfair shot, Ignatieff didn’t know what to say. A seasoned pro like Jean Chrétien or Brian Mulroney would have responded with a counter question like: “Why, Mr. Layton, when you live in Toronto – a mere four hours from the capital, did you and your spouse Olivia Chow (also an MP) bill Canadian taxpayers with expenses of almost one million dollars last year? So much for the average Canadian narrative you like to talk about. By the way, I don’t spend time in Ottawa racking up taxpayer-paid expenses. I am out talking to Canadians.” But it was not to be. Even in defeat, Ignatieff showed bad political judgment. He had not only lost the election; he had lost his own seat in the Toronto riding of Etobicoke-Lakeshore. Instead of resigning immediately on election night, as any seasoned politician would have done, he talked about staying on, helping to rebuild. Ignatieff just did not get it.

Surely, one of the saddest moments of election night occurred when Ignatieff’s caucus colleague, apparent friend and one-time university roommate Bob Rae went on national television musing about how progressives might now unite (code for the Liberals and the NDP to join parties). This untimely and arrogant remark did not go unnoticed by Rae’s former NDP colleagues or Liberals who immediately dismissed the notion. It was an especially bitter pill coming from Rae, the former NDP Premier of Ontario who had contributed to bringing down the government of former Ontario Liberal Premier David Peterson in 1991. As Premier, Bob Rae had been defined by his anti-business policies that drove the Ontario economy into record debt and deficit, a low point of his tenure came in 1995 when Rae was loudly booed during a visit to the Toronto Stock Exchange with his then Finance Minister Floyd Laughren, famously referred to by Liberals and the business community as “Pink Floyd.”

Now Rae was speaking as a federal Liberal MP. With Ignatieff mortally wounded, Rae immediately showed he was prepared to sell the Liberals off to a partnership with his former pals in the NDP. It was a remarkable bit of crass political chutzpah and spoke volumes about Rae’s lack of knowledge of the Liberal Party. By putting his own ambitions ahead of the Party for all to see, he put the nail in his own coffin and buried any chance of ever becoming permanent leader. Ignatieff had not even given his election night speech to concede defeat. Worse was Rae’s suggestion that Harper’s win was not really a win. His reasoning was that if progressives united they would have more votes. It was arrogant in the extreme. The NDP had just won three times as many seats as the Liberals and were now, for the first time ever, the Official Opposition in the House of Commons. The Harper government had just won a clear majority. The Liberals had just been reduced by the electorate to a shadow of its once mighty self. By the end of the evening, Rae and Ignatieff were finished – Ignatieff through defeat and Rae by his own naked ambition displayed recklessly on national television.

Since May 2011, Liberals across the country have been licking their wounds as pundits continue to eulogize the Liberal Party, pronouncing its quick demise after the next election. Are they premature in their prediction? Probably. Canada lives in the centre of the political spectrum and political landscape. The Liberal Party has traditionally been that centre. The real question is can the Liberal Party stop being its own worst enemy, quit bickering and start renewing itself to offer Canadians a real option? In April 2013 in Ottawa, the federal Liberals will pick a new leader. Papineau MP Justin Trudeau and Toronto-based lawyer Deborah Coyne have entered the race and many expect Montreal MP and former astronaut Marc Garneau to jump in. Polls indicate that Canadians seem to want the Liberals back. But the issue is can the Liberals come back with something to offer that Canadians will buy?

To look ahead, it is worth looking back to see how the Liberals ended up as the third party in Parliament and see who is stepping forward to bring them back to the future.

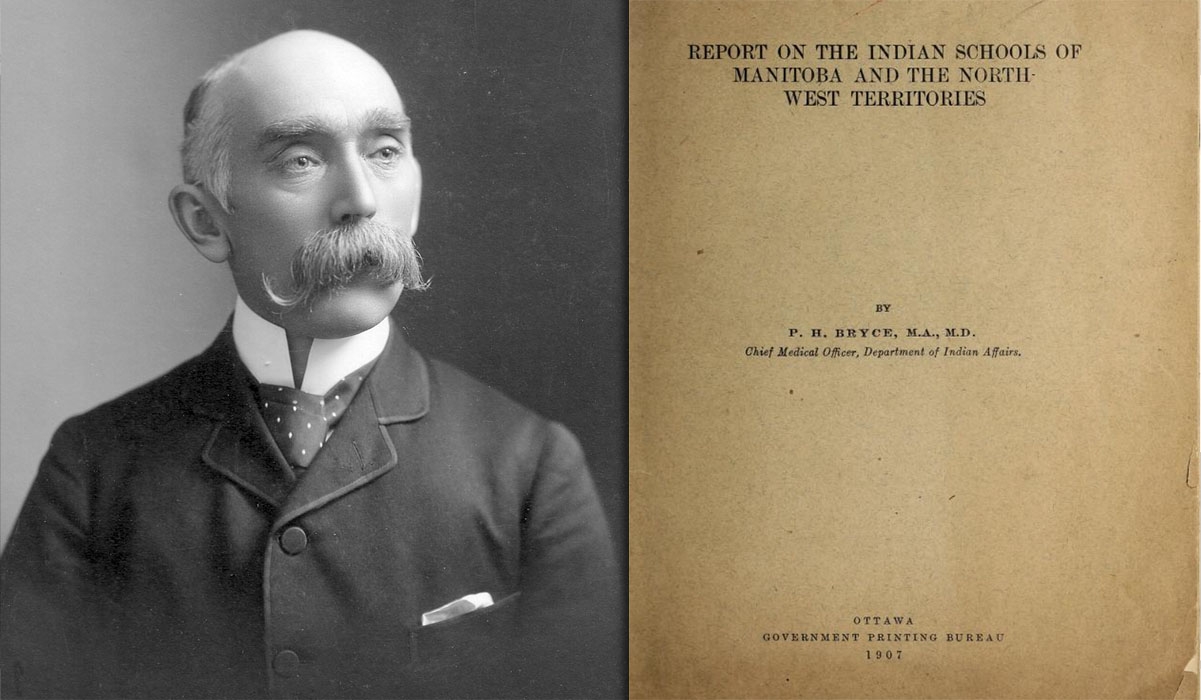

In 1984, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau retired from politics after 16 tumultuous years that changed Canada forever. Trudeau’s role in the patriation of the Constitution, his numerous pieces of legislation to make Canada a fair and just society, and his policies enshrining bilingualism and multiculturalism in Canada stand as great political achievements. Many scholars suggest that the Trudeau-crafted Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms stands as the pivotal document that gave birth to a modern Canada and that the content of the Charter is on par with the great democratic treatises of history, including the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Magna Carta.

However, Trudeau’s extended tenure as Prime Minister left a number of scars on the Canadian political landscape. He had increased the national debt substantially and unilaterally, created the unpopular National Energy Program (NEP), which initiated a political arm-wrestling match between Alberta and Ottawa about the federal government’s control over, and its share from, Alberta’s lucrative petroleum industry — a move which still rankles many Albertans today and is often seen as the underlying reason why the Liberal Party has had little success in electing Albertans and Westerners to Parliament. By the time Trudeau left, the country was redefined but it was also in debt due to massive increases in spending and social programs. On the security and deficit side, Trudeau’s policies had been a failure and the Canadian Forces went through years of neglect and underfunding that impacted Canada’s relations with its allies, particularly the United States and Western Europe. Politically, the Pierre Trudeau experiment had been devastatingly polarizing for the Liberals in Western Canada.

In Trudeau’s last election in 1980, the Liberals won a majority government by winning all but one seat in Quebec and most of the seats in the Maritime Provinces and in Ontario. However, the Liberals won only two seats under Trudeau in Manitoba and were completely shut out in British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

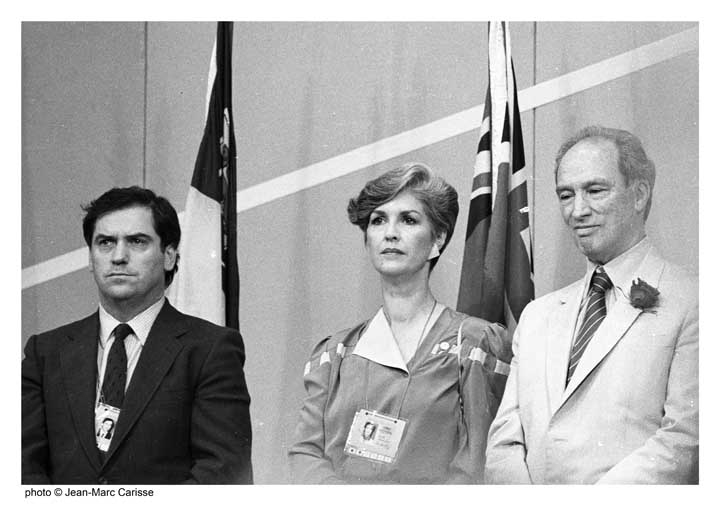

In 1984, seven seasoned cabinet ministers entered the Liberal leader-ship race: John Turner, Jean Chrétien, Donald Johnston, John Roberts, Mark R. MacGuigan, John Carr Munro and Eugene Whelan. Early odds for a winner were on John Turner, a Toronto-based corporate lawyer and former Minister of Finance. Turner, who had run against Trudeau for the leadership in 1968, had a very public falling-out with Trudeau in 1976 over economic policy differences and left politics. By 1984, Turner was seen as the great hope and Crown Prince who would restore Liberal credibility in the West and keep the Liberals in power. At the June 1984 Liberal Leadership Convention in Ottawa, delegates narrowly elected Turner after a come-from-behind campaign surge by Jean Chrétien was defeated. Before announcing to delegates that Turner had been elected the new Leader (and as a result he automatically became Canada’s 17th Prime Minister), Iona Campagnolo, with Turner and Chrétien standing next to her on stage, said that Chrétien “came second on the ballot but was first in our hearts,” inferring that Liberals had not voted for their first choice but had instead only voted for Turner because they thought he would keep them in power. This is the moment that the Liberal Party split into two factions. From then on, the Chrétien-ites became one faction in the Party and the Turner group (who would later back Paul Martin and then Ignatieff) became the other faction.

Turner called a general election in the summer of 1984 to secure his position as Prime Minister in the eyes of the Canadian electorate. He decided that the best way to proceed in the 1984 general election was to distance himself from Trudeau’s record and carve out a new path for the Liberal Party. However, Turner’s awkwardness on the campaign trail, as well as his difficulty in explaining where this new path would lead Canada, made for a lacklustre campaign. Internally, the Liberal campaign was in meltdown mode as Trudeau stalwarts – including Trudeau’s chief political architect and now Turner foe Jean Chrétien – watched as a self-imposed identity crisis paralyzed the Liberal Party. Chrétien wanted to run on the Trudeau record, while Turner wanted to turn the page.

Further complicating matters was Conservative leader Brian Mulroney’s decision to make the 1984 election a referendum on almost two decades of Liberal rule that he said had resulted in crass patronage and tired old ideas. Change was in the air. On the evening of September 4th, 1984, John Turner and his Liberals were whipped by Brian Mulroney and the Progressive Conservative Party, winning only 40 seats and narrowly holding on to their status as the Official Opposition as the NDP placed a close third with 30 seats. It would have been easy for Turner to quit. That is what the Chrétien forces wanted, but Turner was a fighter and even with the massive losses across the country, he had managed to win his own seat in the Vancouver Quadra riding. The defeat reinforced his resolve to make it right and get the Liberals back on top. Over the next four years, the internal politics of the Liberal Party were ferocious as the Chrétien and Turner camps fought behind the scenes. Chrétien resigned from Parliament in 1986 as he recognized that he was not a fit for Turner’s style. Turner won support for his leadership during that period at party conventions but in the spring of 1988, the Liberal caucus led by several disenchanted MPs – many of them loyal to Chrétien – tried to force Turner out. He survived the very public coup but the tactic-savvy Brian Mulroney, seeing the Liberals in disarray, called a federal election on the issue of free trade with the United States.

Turner went into the autumn 1988 general election badly crippled by Party infighting, the recent coup that he had put down, and with the possibility the entire Party could collapse. Between 1984 and 1988, the Mulroney government had negotiated a free trade agreement with the United States. The Turner-led Liberals vehemently opposed the agreement, based on the reasoning that it would undermine Canada’s sovereignty and its manufacturing sector. Although Mulroney would win the election, many cite Turner’s performance in the Free Trade campaign as one of the great political performances in Canadian electoral history. Turner exuded authenticity, especially in the nationally televised debate when in a Socratic and blunt tone directed squarely at Mulroney, he said that Mulroney’s Free Trade Agreement was selling out Canadian sovereignty to the Americans with the stroke of a pen. It was a riveting moment and in the days following, the Liberals surged ahead in the polls. However, the three previous years of infighting had taken their toll and the Party was so low on money that it could not match the avalanche of television ads the Conservatives ran against the Liberals to counter the Turner surge and they pulled ahead in the polls.

On November 21, 1988, Mulroney and the Conservatives were returned to power with a second majority. However, Turner had more than doubled the Liberal seats in the House to 83 with representation from across Canada. He had redeemed himself and the Liberal Party. In Montreal, a very successful high-profile businessman with impeccable Liberal credentials named Paul Martin had also been elected as part of the 1988 Turner Team. After taking the Party through a difficult period, John Turner retired to private life in 1990, setting the stage for new leadership.

Leadership races are a key ingredient in the renewal process of any political party and function as a tool to bring in new members with new ideas and to advance the policy debate across a number of issues. Most of the Turner people would get behind Paul Martin’s leadership bid. They saw Martin as the new man to lead them into the 1990s. Jean Chrétien, the Party populist, in their view was yesterday’s man and “his people” had caused severe damage to the Liberal brand by working behind the scenes against Turner for the past six years.

The 1990 race was a rather testy affair that ended in Calgary in June 1990. Jean Chrétien won a decisive victory over Paul Martin, Sheila Copps, Tom Wappel and John Nunziata. Behind the scenes, it was a rematch between the backroom boys who fought each other in the 1984 leadership. Almost immediately after assuming this position, Chrétien urged the Party to review its definition of liberalism, a move which would signal the first step toward what would ultimately help the Liberals forge a new identity applicable to the 1990s. Internally, he managed the Martin cadre by appointing Martin as the Environ-ment Critic and gave him a key role on the national election team. Chrétien gave Martin some rope but otherwise ran an ironclad office with strict caucus discipline that required compliance.

Two and a half years later, in the winter of 1993, Prime Minister Mulroney announced his retirement. The Conservatives elected a new party leader – Kim Campbell – who automatically became Canada’s 19th Prime Minister. But like her earlier delegate-chosen Liberal counterpart John Turner, Kim Campbell needed to have her position as Prime Minister of Canada confirmed by winning a general election. This did not happen. In the fall of 1993, the Conservative brand had been tarnished by Mulroney’s then wildly unpopular Goods and Services Tax, which he implemented on New Year’s Day 1991, as well as by a weak economy resulting from the lingering recession. Early in the 1993 campaign, Chrétien unveiled his Party’s election platform entitled Creating Opportunity: The Liberal Plan for Canada, which came to be widely referred to as the Red Book of election promises. While Chrétien’s skill in selling his Party’s Red Book to Canadians would play a role in the Liberals’ 1993 victory, the high unemployment rate and the sluggish Canadian economy would be the underlying catalyst that would propel the Liberals to power. When the dust settled on the evening of October 25th, the Conservatives were swept out of office, losing 154 of their 156 seats in the House of Commons as well as official party status.

Once elected, Chrétien named Paul Martin his Finance Minister and together they would run one of the most efficient governments and produce the most balanced back-to-back budgets of any government since the glory days of C.D. Howe and William Lyon Mackenzie King. In the spring of 1997, with the Opposition Reform Party and former Conservative Party fighting out their internal battles and the separatist Bloc Québécois controlling the majority of seats in Quebec, Prime Minister Chrétien called a general election, and, on June 2nd, the Liberals won another majority government because of an improving economy, strong support in Ontario for Chrétien’s economic policies and his determination to slay the federal deficit, and a general resonance for the Party’s emphasis on national unity – a particularly visceral issue since Chrétien’s federalist forces had narrowly won the October 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty, which would halt the Quebec separatists’ secession agenda for a generation.

At a practical level, the Chrétien-Martin austerity program to slay Canada’s deficit and get its financial books in order was one of the greatest achievements of any government in a half century. The Chrétien government’s tough measures and disciplined approach to the country’s finances produced results. By 1998, Canada’s deficit had been whittled away and the budget was balanced. Throughout the remainder of Jean Chrétien’s term as Prime Minister, with Paul Martin as Minister of Finance, Canada would continue to enjoy stellar economic growth and balanced budgets.

However, throughout this entire period, the Liberal Party’s internal family feud between the Martin and Chrétien forces was not contained – it was growing and getting out of hand.

In the fall of 2000, Prime Minister Chrétien called what would be his final election. He sought to simultaneously win another mandate from the Canadian people, stunt the growth in popularity of the western-based Canadian Alliance and circumvent a possible merger between the Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives. Chrétien won a third consecutive majority government. However, this victory seemed to frustrate the Martin-ites as they saw that Chrétien seemed to be intent on staying Prime Minister for some time to come. To counter this, they accelerated their process of taking over Liberal riding associations and the key positions and structures of the Liberal Party of Canada.

By November 2002, at the very time the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservative Party united to become the Conservative Party of Canada, the Martin Liberals had taken full control of most of the riding associations across Canada and were now in a position to force Chrétien from power. Seeing the writing on the wall, Chrétien announced he would leave, in late 2003, even though he was still a very popular Prime Minister and leading in the polls. There was no leadership race or any chance to bring in new members or have a debate about issues. Because Martin’s people controlled the vast majority of ridings and since the leadership was decided by delegates from those ridings, it was clear the process had been hijacked and Martin would be anointed leader. Several Chrétien Cabinets ministers wanted to run, including Finance Minister John Manley, Health Minister Allan Rock and others, but they knew it would be impossible to win because the delegate selection process was controlled by the ridings; a majority of which were controlled by Martin. On a purely tactical level, it is hard to fault Martin’s team. They wanted their man to be PM and Martin wanted the job. It was realpolitik in overdrive. Cabinet Minister and Former Deputy Prime Minister Sheila Copps put her name on the ballot on principle and gave it a run anyway. She would pay for it later with some pretty shabby treatment by the Martin people when she lost, but she never lost her self-respect. It is why today people in the Liberal Party still admire Sheila Copps – always a fighter.

On November 14, 2003, Paul Martin became the leader of the Liberal Party, capturing 93 per cent of delegate support. On December 12th, 2003, he became Canada’s 21st Prime Minister. There was no real race, no renewal of the Party, no surge from young people who were excited to be behind a series of candidates who would fight out a battle of ideas to become the next Liberal Leader. The same month the Reform Party and Progressive Conservative Party united to become the Conservative Party of Canada, which would be led by newly-elected leader Stephen Harper, who proved to be a worthy adversary and tied Martin and the Liberals to an ongoing sponsorship scandal (AdScam or Sponsorgate, as it was known), which undermined the confidence many Canadians had in the Liberals.

Being well aware of the negative fallout that the sponsorship scandal was having for his Party, Prime Minister Martin campaigned in 2004 in a fashion that distanced himself and his Liberals from the government of his predecessor, Jean Chrétien. Behind the scenes, the Martin team blamed the entire scandal on the Chrétien people. Yet this strategy came with a substantial catch for the Martin government: it meant that he also had to distance himself from his Party’s achievements and his own personal achievements while serving as Chrétien’s Minister of Finance. Ironically, many of these same Martin advisors had given John Turner the same advice in the 1984 election. Run against your achievements – in fact, run away from them. As political scientist Stephen Clarkson put it: “The Martinites’ disowning of Chrétien over AdScam prevented them from claiming ownership of Martin’s great economic achievement as finance minister — eliminating the budgetary deficit and presiding over robust growth rates that improved Canada’s economic position to the point where it was the only G7 country to enjoy both fiscal and trade surpluses in 2002.” These drawbacks likely contributed to the election’s outcome: a Liberal minority government.

The sponsorship scandal continued to plague Prime Minister Martin and his Liberals, so much so that in November 2005, the opposition parties in the House of Commons voted to pass a motion of non-confidence in the government. Having lost the confidence of the House, the Martin minority government was forced to head to the polls. On January 23rd, 2006, when the votes were tallied, nearly 13 years of Liberal rule had drawn to a close. It was Stephen Harper and the Conservatives who would now form a new minority government. Paul Martin, re-elected MP for LaSalle-Émard, would continue to represent his constituents in the House of Commons before eventually exiting politics in 2006. Martin and Chrétien had achieved great things for Canada together. However, their rivalry had also come with costs. Their respective political teams were so adversarial towards each other that it began to eat away at the stability of the Liberal Party itself. With their departure, the “family feud” between the factions remained.

Heading into the December 2006 Liberal Leadership in Montreal, The Liberal Party Establishment was clearly split in two with many of Chrétien’s former backroom people supporting Bob Rae, the former NDP Premier of Ontario and Liberal adversary – and brother of Chrétien’s closest aide John Rae – while most of the former Martin-ites lined up behind Michael Ignatieff. Rae was viewed with great suspicion by many in the Party and Ignatieff was seen by many as a candidate contrived by the party establishment – an intellectual who had spent most of the previous three decades outside of Canada. Rae was positioned as a Liberal who could capture NDP support and Ignatieff was positioned as an intellectual and policy wonk with charisma.

However, the vast majority of Party delegates were fed up with the establishment. Most lined up with Stéphane Dion, Gerard

Kennedy, Ken Dryden, Scott Brison, Joe Volpe and Martha Hall Findlay. In a shocking twist, newcomer Martha Hall Findlay won about 100 more ballots on the first vote than expected. Findlay had shown some grit in travelling the country in a red bus looking for support. She had almost defeated the Tory Candidate Belinda Stronach in Aurora-Newmarket in the 2004 election. Hall Findlay was prepared to give it another go at Stronach and the Tories in the follow-up election but when Stronach crossed the floor in 2005 and joined the Liberals under Paul Martin (and staved off a vote that would have defeated the Martin Liberal Minority in Parliament), Hall Findlay was left without a seat as the Party establishment promised Stronach she could run in Aurora-Newmarket as the Liberal candidate. Hall Findlay was not consulted on this by the Party. She had singlehandedly built up support for the Liberals in the riding to have it stripped away without any say. She was not offered another seat. So she ran for the leadership.

After the first ballot, Hall Findlay walked with her votes into the Stéphane Dion camp. Dion and another Liberal candidate, Gerard Kennedy, had agreed they would join forces after the second ballot – whoever was ahead would continue on. Hall Findlay’s decision to go to Dion gave him enough votes to pass Kennedy on the follow-up ballot and Kennedy then joined Dion, which gave him enough votes to force Rae off the ballot. Most of Rae’s people went to Dion – also a Chretien protégé – and a Dion victory ensued. The Party delegates won while delivering a snub to the establishment. However, Dion’s tenure would prove to be disastrous.

Dion’s main problem was that he did not take advice and was very hard-headed. His focus on a carbon tax above all else was demonized by the Tories. In the 2008 election, the Conservatives picked up more seats in the crucial province of Ontario, while the Liberals lost almost two dozen seats with a continuation in the lack of support that led to their loss of power in 2006. Dion’s carbon tax policy proved fatal for the Liberals at a time when the global economy was in free fall and when the memory of record-setting oil prices that summer was still fresh in the minds of Canadians. The result of the 2008 general election was a second Conservative minority government led by Stephen Harper. When Dion, with Bob Rae’s support, and the now much smaller caucus made a move to stop Harper from governing by forming a coalition government with the Bloc Québécois and NDP (against the advice of many in the Party), it proved catastrophic. Ignatieff did not commit to the deal and made it public that he was uncomfortable with it. The idea that Dion would prefer to govern with separatists whose sole purpose was to destroy Canada as we know it rather than a Conservative government committed to Canada proved to be the final straw. After significant pressure from the Caucus and the Ignatieff team, Stéphane Dion would step down as Leader of the Liberal Party.

At this point, Ignatieff’s team was pitching the line that the Party was close to bankruptcy and that it could not afford another leadership convention to democratically elect a new leader. It would cost too much and was not necessary since there was this brilliant guy Michael Ignatieff who came second last time and was the current Deputy Leader and he could easily beat Harper. So, for the second time in seven years, the Liberal Party of Canada anointed a leader. No excitement, no campaign, no renewal. On May 2nd, 2009, Ignatieff – the renowned historian, academic and alumnus of Oxford and Harvard – was elected Leader of the Liberal Party and assumed the Office of Leader of the Official Opposition, a position he would retain until the crushing defeat of May 2011.

On April 14th, 2013 in Ottawa, the Liberals will select their next leader using a new untested “open convention” nomination process. In an attempt to capture the attention, votes and loyalty of younger Canadians (and also to reduce the influence of the traditional Liberal Party establishment), any Canadian citizen who is not a card-carrying member of one of the other federal political parties can vote for their choice of Liberal leadership candidate without having to join the Liberal Party.

The stakes could not be higher. Ironically, the same Liberal establish-ment that anointed Paul Martin and then Michael Ignatieff is now suggesting that Justin Trudeau, the 40-year-old son of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, is the only answer for the Liberals. To be fair to Justin Trudeau, he did not ask to be anointed. Given his father’s legacy, the Trudeau name can be both a blessing and a curse in Canada. However, Justin Trudeau does bring a number of vital assets to the race: the key being name recognition and excitement. Pundits say he is a lightweight but that is unfair. He has surrounded himself with knowledgeable people; he is a charming orator, a quick study on issues and is well travelled in Canada and abroad.

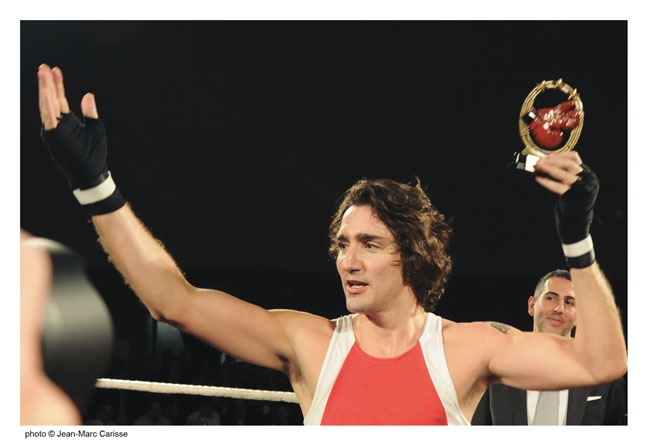

He also has grit. He sent Ottawa into a frenzy last spring when he knocked the lights out of tough-talking Tory Senator Guy Brazeau in a charitable boxing match. In a room packed with Tory aides and MPs, Trudeau walloped Brazeau in the ultimate mano-a-mano fight. In a pre-fight press conference to promote the charity, Brazeau weighed in with a Speedo-like thong, long shoulder-length hair and mouthy attitude. Trudeau showed up in red and white trunks with his wavy hair and polite smile. The loser would have his long hair cut by the winner and wear the opponent’s party shirt and emblem for a week. On the night of the fight, Trudeau took some early hard hits and then after rope-a-doping Brazeau, proceeded to systematically clean his clock. What most did not know is that Trudeau has trained in a Montreal gym at Olympic-style boxing since he was in his twenties. You’d expect that – given he is Pierre Trudeau’s son – he is not going to get into a fight he can’t win. Just ask Senator Guy Brazeau. That is where Justin Trudeau should not be underestimated. He is not afraid of risks. He twice won election in his Montreal-area Papineau riding against serious Bloc Québécois opponents… choosing the hard road instead of a sure-thing riding. To date, his tenure in Ottawa has been unremarkable. But so was Stephen Harper’s before he became PM. Remember Harper had only been a political aide, a Member of Parliament and the head of the National Citizens Coalition – a lobby group – before becoming leader and PM. Trudeau has been tested twice in street politics and was a high school teacher and has a couple of university degrees. Most polls show Canadians have a high regard for teachers. The danger for the Liberal Party and for Justin Trudeau is that if no credible person runs against him in the leadership race, it could actually hurt him and the Liberal Party. Then the net effect of his entering the race could be the same as when Paul Martin ran in 2003 – he is viewed as unbeatable so there is no real race and Trudeau wins by anointment. He gets the Party leadership without being tested.

It is a tough decision for candidates because to enter they must pay a $75,000 fee to the Liberal Party. A dream pick for many Liberals is the Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney. They believe Carney could beat Trudeau and then defeat Stephen Harper. Others mentioned include Montreal MP (Westmount–Ville-Marie) and former astronaut Marc Garneau, Ottawa South MP David McGuinty, British Columbia MP and former MLA Joyce Murray, former Justice Minister Martin Cauchon, University of Ottawa President and former Minister of Health and Minister of Justice Alan Rock, Ottawa lawyer David Bertschi, former Ajax Pickering MP Mark Holland and former Willowdale MP Martha Hall Findlay. Lawyer Deborah Coyne has entered the race but did so even though she lost in a run for Parliament in Toronto Danforth in 2006. Bertschi, Holland and Hall Findlay are all considered long shots because they lost in the 2011 election. Many in the Party assumed New Brunswick MP Dominique Leblanc would run, but he is backing Justin Trudeau.

When speaking during an exclusive interview for Ottawa Life Magazine, former Liberal Prime Minister Paul Martin expressed a great deal of optimism about the 2013 leadership race, saying that: “This coming year’s convention will give the Party a real shot in the arm and will provide great momentum and give the Liberal Party exactly the opening it needs.” But what kind of “opening” does the Liberal Party require? Paul Martin sheds some light on the matter by stressing that: “The current Canadian political climate is looking very favorable for the Liberal Party of Canada. This is because the entire progressive wing of the Conservative Party (or what used to be referred to as the Progressive Conservative Party) has left the scene.” Martin maintains that this trend will have negative ramifications, the most important of which signals that “we are heading in the direction of the extreme political polarization that you see in the United States.” Martin is adamant that an opening exists for the Liberal Party of Canada since “in Canadian politics at the federal level, we now have an extreme right-wing government with an extreme left-wing opposition.”

While the once formidable Liberal coalition – francophones outside Quebec; federalist francophones in Quebec; multicultural communities; blue-collar workers in the industrial cities of Ontario; progressives, business people and environmen-talists in the West; Atlantic Canadians in St. John’s, Halifax, Moncton and Saint John; the “business class” Liberals from Toronto – still exists, it has just not found a reason to coalesce around what was being called the Liberal Party in recent years. Previously, this impressive coalition mobilized at election time to secure the big ideas and values for which Liberals stood. When there are no big ideas or values present, people stay at home or join the other team.

Pessimists will argue that the country has passed the Liberals by. They say that the Liberals have become a collection of dilettantes and self-righteous intellectuals who get elected in pockets here and there. They say Liberals live on past glories and are not in a serious position to contend for power. The thing is that even though some of this is true, there is still a bright light burning for Liberals. Even the smartest NDP strategist will acknowledge Quebecers voted for Jack Layton, not the NDP; that the Harper government, despite its huge advantages, can’t break above 40 per cent in the polls due to its polarizing and prickly ways. The Liberal Party, like Canada and Canadians, remains a fundament-ally progressive, pragmatic, fiscally conservative entity. The Liberals’ problem is that they have not defined who they are and what they want to do since the day Jean Chrétien retired in 2003.

Paul Martin became Prime Minister but then ran away from his record with Chrétien which may have caused his premature demise after an exceptional political career. Stéphane Dion was in over his head and Michael Ignatieff was a nice guy with zero political instincts who was ravaged by his own inexperience. Bob Rae – the one-time chameleon and current interim Liberal Leader – seems to have come into his own Liberal skin since he announced he would not seek the Liberal Leadership in April 2013. As Interim Leader, Rae and the Liberal Caucus have performed well in the House of Commons and kept the Liberals front and centre and very relevant against the Mulcair-led NDP.

With Rae out of the race and focused on Harper, the Liberals can finally focus on redefining and reinventing themselves as they have done so many times in the past. But this will not be easy. The Liberal Party needs to pick a centrist, pragmatic, substantive, bilingual, charismatic, smart, expe-rienced and likeable person if they want to defeat Harper and put the NDP back into its traditional third-party turf. With Justin Trudeau, Marc Garneau, Martin Cauchon or Deborah Coyne, they can go back to their future and recapture the centre. The political middle – those Canadians who fall neither into the camp of the extreme right nor of the extreme left – is open for representation. But as a former Prime Minister of Canada and also a long-serving Minister of Finance, Paul Martin is quick to point out that: “Nothing is easy in politics.”

TOP PHOTO: JEAN-MARC CARISSE