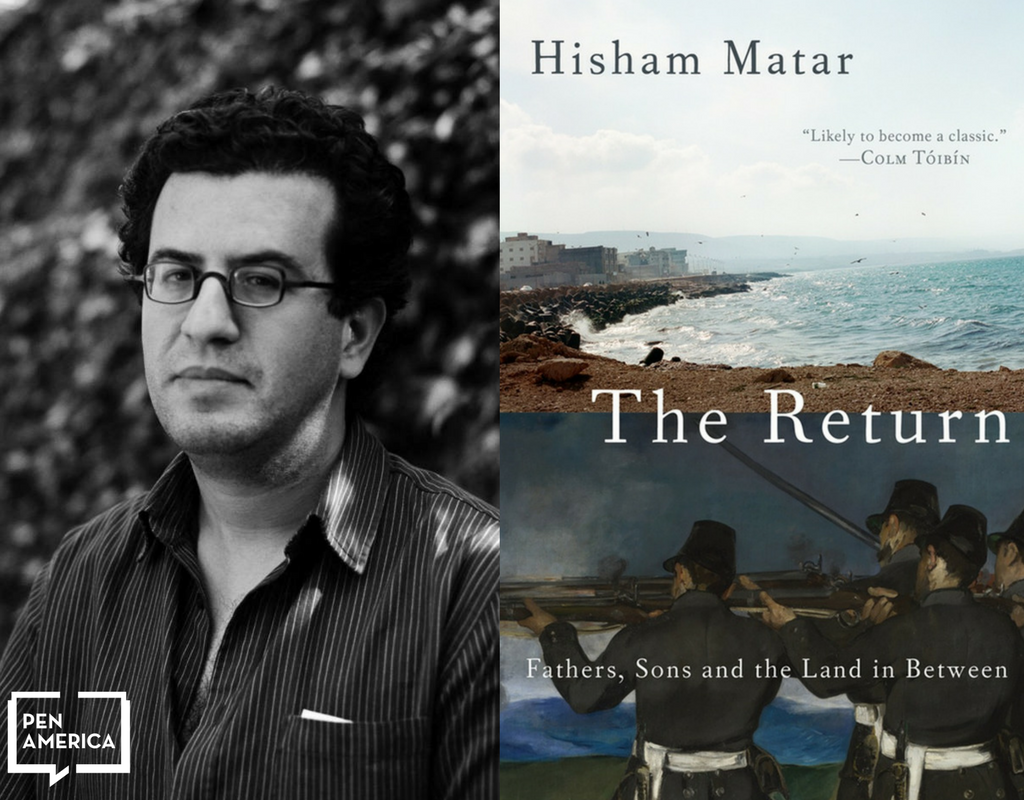

Book Review: The Return – Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between

By Hisham Matar

Hisham Matar’s memoir is a beautiful and heartbreaking read.

On September 1, 1969 Libya’s first post-colonial head of state, King Idris, was overthrown in a coup by General Mohammad Qaddafi. Like the Arab spring of 2011, there was a thirst for change and respect. Not long after, however, there were ominous signs that Qaddafi was hijacking the revolution’s promise. Committees were created meant to infiltrate every aspect of Libyan society. Dissidents were identified and captured. Their fate was understood if not always verifiable: they were tortured and often killed. Those not killed were left to languish in prisons, like that of the infamous Abu Salim.

The threat was hardly short lived and extended to those in exile. In March 1990 Jabulla Matar, one of Libya’s most prominent dissidents, was captured in Cairo by the Egyptian secret service on behalf of the Qaddafi regime. He had a wife and two sons, Hisham and Zian. Hisham was 19 years old, Zian a few years his senior. The experience, it goes without saying, would haunt the entire family. Hisham was studying architecture but always had a passion for writing and literature. He would later write the award winning novels In the Country of Men and Anatomy of a Disappearance. Both novels feature young boys whose early education about the world involves hints about clandestine politics and fathers who are captured, tortured and killed by the military regime. There are obvious parallels between the young protagonists of his novels and his life as a young man whose own father was captured and imprisoned by Qaddafi. All three are scarred and all will struggle to understand the life altering experience.

Hisham Matar documents his struggle in his remarkable memoir, The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between. The different questions that go to the heart of the book are informed by his anguish over his father’s imprisonment and the unresolved questions it left in its wake. How do you live in freedom when you know your father has been imprisoned and tortured, quite possibly to death? How can you let go when your father’s ultimate fate is still unknown? Is it possible that his father, like thousands of other prisoners, survived the torture and deprivations? The need to answer the last question especially fuels his understandable obsession. Hisham must learn of his father’s fate. He is prepared to follow any clue, uncover every stone, talk to any person who might yield insight into what happened to his father. The Sisyphean task takes him back to Libya after living many years in exile and closer to those inside the regime than he would otherwise have any desire to be. The Return thus works on many levels. It reads like a brilliantly written detective story. It is also powerful lament for Libya’s tortured past and failed hopes. Most importantly, it is a poignant and often heartbreaking account of a relationship between a missing father and his son.

It’s easy to understand why Jabulla Matar would be regarded as a threat to a dictatorship. As Matar relates, his father embodied everything that a dictator would despise: independence, intelligence, determination, charisma and generosity of spirit. Jabulla was a learned and cultured man who, the reader learns, walked with an air of dignity and, when pushed, defiance. “My forehead does not know how to bow,” Jabulla wrote in one of the few letters written in prison that was somehow delivered to the family. He also recognized dark omens when he saw them. Not long after Qaddafi assumed power, Jabulla understood he wasn’t a revolutionary leader but a dictator severely intolerant of dissent and democracy and with a potential for ruthlessness. It was a type of political leadership and direction for his beloved country he could not tolerate. As Hisham writes, his father’s leadership abilities soon led him to organize a campaign of resistance. He formed cells based out of Chad. The family moved to Cairo. All efforts were taken to hide their identity, to protect the family. Still he understood he would be become a target of the regime. There would be little news of his fate and no opportunity to see him until the spring winds originating in Tunisia blew through Libya in 2011.

The trajectory of Libya’s failed Arab Spring is too often reduced to a two stage process: Qaddafi’s ouster and death and the fall of his regime, followed by a prolonged decent into tribal violence and chaos from which the country has not yet emerged. The Return is revelatory for many reasons, among the most crucial of which is the window it opens on the time between these two stages. As happens in spring, hope and optimism bloomed like May flowers in Libya in the early months following Qaddafi’s demise. The hope wasn’t simply for some semblance of democracy and the rule of law. Hisham Matar’s return to Libya seemed to symbolize, at long last, the potential for a cultural renewal. His novel In the Country of Men had been banned by the regime. More absurdly, his name could not even be mentioned in the press. Now people were organizing a literary event (appropriately held at a library without books that the regime had allowed to fall to pieces) to celebrate his books. Many of the hundreds who attended were dressed in suits as a way of marking the event’s importance.

Libya’s spring opened a window of optimism and possibility not only for the country as a whole but for particular families like the Matars. For it wasn’t simply Jabulla who was imprisoned by Qaddafi’s regime. So too were his brothers Mahmoud and Hmad, as well as various cousins. The threat of imprisonment had the unintended effect of scattering other members of the family across the globe. Hisham lived in London, his brother Ziad in Egypt, others elsewhere. In a futile bid to quell the tides of change sweeping across the Arab world, Qaddafi released hundreds if not thousands of prisoners, some of whom were members of Hisham’s extended family. (The regime’s efforts to appear more open and conciliatory were countered by a crackdown on journalists and others who still dared to openly criticize it.) Hisham returns not only to find out what happened to his father but to reconnect with family members whose fate was also unknown.

The Return is thus also about a the reunion of an extended family whose history was tragically shaped by the Qaddafi dictatorship. Matar writes beautifully and mournfully about these reunions with uncles and cousins he hasn’t seen for decades. His Uncle Mahmoud shares with him painful, tragic stories about his and his brothers’ imprisonment. Upon finding himself in Abu Salim, every night for one week Mahmoud hears a man only a few cells away reciting poetry. It is Jabulla but the voice is so altered that his brother doesn’t recognize it. Jabulla then makes references that only Mahmoud would understand. Only then does Mahmoud believe that it was his brother reciting the poetry. The reader is left to ponder the scene’s tragic absurdity.

Matar writes with cool precision and with a novelist’s eye. He writes beautifully about how the light falls in Benghazi and how the sea shaped his hopes as a young boy and how his father taught him to swim. The precision with which he writes also serves a deeper purpose: it acts as a counter balance to his simmering outrage and unrelieved sadness. “Rage, like a poisoned river, had been running through my life ever since we left Libya,” he reflects. Writing, the reader feels, imposes a discipline he might not otherwise be able to sustain. It’s a way of productively channelling his rage. He writes about the brutality of Italy’s occupation and the role his Grandfather Hamed had in the resistance. Indeed resistance runs in the family. But to what end? Libya again has been plunged into a state of near anarchy and extreme violence. A place from which most Libyans long to escape. Some of those who celebrated his return would later be killed. It’s no wonder that a writer as thoughtful as Matar is going to feel despair and always off balance.

Matar’s struggle to find balance is most manifest when he reflects on the effects of his father’s imprisonment on himself. He’s incessantly pulled in different, severely contradictory, directions. His hatred for the regime and what Qaddafi in particular did to his father and indeed the country must be contained when granted the opportunity to meet and have further communication with Qaddafi’s son, Seif. Seif may be a fraud but he holds the key: he will know of his father’s fate and, if he’s alive, could secure his release. Hisham must thus not succumb to rage and impatience and instead tolerate Seif’s perpetual obfuscations and delays in communicating to him information about his father. Hisham craves certainty but is fearful of losing any remnants of hope that his father is still alive. But that hope is often no match for the despair fuelled by the imagination. He’s tormented by mental images of what his father endured for so many years: the torture, the loneliness, the indignities, the loss of freedom and the achingly slow withering away in a tiny cell. He would dearly love to see his father alive but has a deep fear of not being able to recognize him if that were to happen. The pain these tensions bring to bear is so acute that Matar considers suicide. It’s the memory of one of his father’s maxims that saves him. “Work and survive,” Jabulla would say to his young sons. Work and survive. All that maybe left of Jabulla are such echoes from the past. But in this way and others, Matar relates, his father becomes an active absence, as though he resides somewhere between life and death. They are enough to pull Matar from the brink. He instead makes the choice to write, first his novels and now this memoir, at once agonizing and beautiful.