Delusions of adequacy: How Russia and Pakistan lie to themselves in similar ways

The ongoing assault on Ukraine by Russia has drawn plenty of comment, with the focus primarily on those aspects that are now apparent at a glance, and are particularly troubling. They are easy to list. The Russian action is evil. Its justification was absurd. Its conduct has been incompetent beyond measure. It is and will continue to be a catastrophe for both nations. The behaviour of Russia, including systematic war crimes, will make it a pariah state for the rest of my life and longer, and the sustained world response will beggar the Russian people for a generation. Ukraine, with somewhat inadequate but clearly useful military assistance from NATO nations, will survive, and it will subsequently receive considerable development assistance from NATO states for its rebuilding.

All this has come about because of one great lie. And it is not the vulgar and noxious lie that Mr. Putin tells, in which he claims that the Ukrainian people and nation do not exist. It is an even bigger lie, and it is one that not only Mr. Putin, but many prominent Russians tell themselves all the time, and actually believe. It is the lie that Russia is a great power, and a peer competitor (or peer opponent) of the United States of America.

Interestingly, it is exactly the same lie that prominent leaders in Pakistan tell themselves about Pakistan being the peer competitor (or peer opponent) of India.

The truth is that the only fact which underpins this fallacious notion, in both cases, is a tally of nuclear weapons, which shows rough parity. Russia and the US have more or less comparable nuclear arsenals, at roughly 4,000 useable warheads each. On a much smaller scale, India and Pakistan each have about 160. But parity in a class of weapon which cannot be used without serious risk of utterly destroying the nation that uses it is hardly a guarantor of success in all the forms of competition that are actually meaningful for human life. An unused but available nuclear arsenal is a useful guarantee against being overrun, but it is always a two-edged sword sort of problem. Having it and not using it very likely guarantees continued existence, but does not automatically confer influence, or even respect. Ask North Korea for details. Furthermore, having it and using it probably moves the needle over into a competition for best ritual suicide.

In every other conceivable measure, Russia and Pakistan are lying to themselves every day. Russia has about 44% of the population of the US, and about 15% of the population of the NATO Alliance. Similarly, Pakistan has about 16% of the population of India, and, in fact, there are slightly more Muslims in India than in Pakistan. (Russia’s population is not growing and is already less than 2/3 that of Pakistan).

The GDP of Russia is well under 8% of that of the United States. In fact, in 2021 the GDP of Russia was perhaps two or three percent higher than that of Canada, but given the impact on its GDP of the current war, it is now very likely less than that of Canada. The GDP of Pakistan is just over 10% of that of India.

The GDP per person in Russia is less than 16% of that in the US. The GDP per person in Pakistan is about 61% of that in India. Clearly, people in the US are vastly better off than their counterparts in Russia, and Indians are better off than Pakistanis by a substantial margin.

Then there is the small matter of corruption and its corrosive effects. The international Perceptions of Corruption Index, a well-regarded and generally unbiased product of Transparency International, uses a rating scale that goes from 100 (corruption free) to zero (corrupt in every conceivable respect). They rate both Russia and Pakistan in the lower, very corrupt range, with scores of 29 and 28 respectively. India scores markedly better, putting it in the middle tier at 40, and the US makes it into the more satisfactory upper tier at 67. (Parenthetically, Canada scores even a bit better, at 74. I assume that our national propensity for apologizing for just about everything probably makes corruption and its necessary coverup a tad impractical.)

In a corrupt state, many institutions are eroded, and both Russia and Pakistan consequently have very weak civil institutions, so that a failure of probity extends into all aspects of life. To be fair, there is perhaps some differentiation between the two states, in a few respects. For example, the erosion of the autonomy of the courts is not quite as extreme in Pakistan as in Russia.

Democracy is also commonly a victim of corruption. The Democracy Index is a complex annual compilation done by the research division of the Economist Group, which also publishes The Economist weekly newspaper. In the most recent tabulation, Russia scored 3.24 and was classed as “Autocratic” versus the US, which scored 7.85, yielding a classification of “Flawed Democracy.”

Pakistan scored 4.31, resulting in its classification as a “Hybrid Regime,” while India scored 6.91, and was classed as a “Flawed Democracy.” (Canada, interestingly, scored 8.87, and was classed as a “Full Democracy”).

Again, to be fair, Russia was, a generation ago, briefly, a sort of flawed democracy, and Pakistan has slipped into the autocratic zone every time the army gets fed up with the government and stages a coup, which has indeed been a recurrent feature of its history.

But both Russia and Pakistan face a huge impediment if they ever wish to recover from being non-democratic states clothed in the fake machinery of a democracy. That impediment is the exaggerated influence of the security and intelligence apparatus in both countries. The ISI in Pakistan and the FSB in Russia have political influence far beyond anything, which could be described as a legitimate remit for a security and intelligence agency. There would not be space in this entire magazine to list their overreach. They also tamper hugely in the international arena. By way of example, the ISI created the Taliban so that Afghanistan could become a convenient, impoverished buffer/client state, and the FSB intimidates and assassinates critics at home and abroad. (Parenthetically, these agencies do not seem to grasp the negative consequences to their parent states of their overreach and foreign meddling. Afghanistan now supports groups that are actively subverting Pakistan, and the widespread revulsion of attacks by the FSB on dissenters and opponents has hardened both domestic and foreign opposition to the regime.)

Using any rational measure, Russia and Pakistan are clearly not even close to being peer competitors of the US and India, respectively. So, what are they? Crudely stated, they might both be described as “banana republics with nuclear weapons.” A more courteous terminology might be “corrupt impoverished dictatorships with nuclear weapons.” So, while it is important to stop treating them like the peer competitors that they wish they were, but aren’t, their true status leads us to ponder an important question: how does one handle banana republics with nuclear weapons?

The short answer is, “always carefully, but with variations that depend upon their posture and behaviour.” In looking for more clarity, we are somewhat lucky in that we already have some experience along these lines. The pilot study for how to handle such a state is our experience with North Korea. As I have already mentioned, North Korea’s nuclear weapons do influence how others deal with that state. On the plus side, no nation state would consider carrying out a “small” military chastisement of a nuclear North Korea for fear of a nuclear retort. So North Korea is protected by its nuclear capability in that narrow sense. It might be said that the nuclear capability guarantees the existence of the state.

But its nuclear capability does not guarantee its good health. For a start, the creation and maintenance of such a capability is costly, almost beyond measure, especially for an already impoverished kleptocracy. And, in the case of North Korea, international anger at its choices and behaviour guarantees that it will be economically, technologically and socially isolated. The nation, and its citizens will not have access to goods or channels of commerce, and will not share in any of the benefits of globalization of trade. They will be safe, but in a small, unpleasant cage. Their defence is also their imprisonment.

And there is an even greater down-side risk to a state like North Korea maintaining its nuclear capability. In the event that it did become embroiled in an active military confrontation, its nuclear capability might very well convince an opponent that a massive first strike was the least bad option. So, while it can not be attacked, it must be wary about attacking others, because of the potential for a self-protective overreaction by a more powerful opponent. In short, its nuclear capability is a great deterrent, but a useless weapon.

How much does our understanding of the situation with North Korea inform our possible stances with respect to Russia and Pakistan? While there are some analogous elements, there are also clear differences in both cases.

The key area of international friction for Pakistan is its list of unresolved disagreements with India. Beyond that, while Pakistan clearly has major failings in the area of human rights and does have a dubious record of encouraging terrorism, it is still open to adequate relations with most of the liberal democracies, and it did accept considerable US advice and financial assistance for a comprehensive program to safeguard its stockpile of nuclear weapons and to create a command-and-control system that militates against accidental or rash use. This relegates its territorial disagreements and religious conflicts with India to a sort of chronic manageable slow burn. There is little evidence at this moment of a need to isolate Pakistan in the same way as the world has needed to isolate a chronically confrontational rogue nuclear state like North Korea.

Russia, on the other hand, is much more problematic. After the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia had appeared to settle into a pattern of simply being a mendacious nuclear-armed kleptocracy with an exaggerated sense of self-importance.

This exaggerated sense of self-importance is also somewhat amplified by the historical accident of the timing of the creation of the United Nations in 1945. On the heels of the Allied victory against the Axis Powers in the Second World War, this new international forum, created to replace the League of Nations, was designed to accord five of the most prominent victorious states a whip hand when it came to crises of peace and security. Thus, the five permanent members of the Security Council of the UN were each accorded veto power over resolutions of the Security Council. The five permanent members were the US, Britain, France, China and the USSR.

Following the dissolution of the USSR, Russia insisted that it was the continuing state for the purposes of the USSR’s membership in the UN and its permanent membership on the Security Council, and while the UN has tacitly acquiesced to that notion thus far, it has never been tested before any adjunctive body. This contrasts with the extensive process that was used when it was determined that the Peoples Republic of China should take over the membership and the permanent seat on the Security Council that had been allocated to China, which culminated with the passage of resolution 2758 of the General Assembly of the UN in 1971.

Given Russia’s actions in Ukraine, there now arises a modest risk that it might be challenged on its right to the USSR’s permanent Security Council seat, and might need to re-apply for ordinary membership in the UN. After all, the population of Russia is well under half of the population of all the states that made up the former USSR, despite being the largest single state arising from that dissolution. And, amongst the veto-carrying permanent members of the Security Council, it is already an outlier, being, in economic terms, by far the least consequential, with less than two thirds of the GDP of France.

In early March, 141 nations in the UN General Assembly voted for a resolution demanding that Russia “immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders.” Only five of the 193 UN members voted against the resolution. It remains to be seen whether this level of solidarity in the General Assembly can be brought to bear on correcting the egregious error of Russia’s membership on the Security Council.

The more recent resolution of the UN General Assembly that suspended Russia from the UN Human Rights Council passed 93 to 24, with 58 abstentions, even after extensive Russian lobbying, in which Russia made it clear that it considered even abstention to be an unfriendly act. So, clearly, Russian diplomatic bullying is less than fully effective now that the world has had a sustained and egregious demonstration of Russia’s inflated sense of self, massive incompetence and lack of morals.

That vote is historic, because it makes Russia the first permanent member of the UN Security Council to ever have its membership revoked from any United Nations body.

So perhaps a challenge to its permanent member status on the UN Security Council is not completely out of the question.

Beyond that, the containment of a truculent Russia is somewhat similar to that of North Korea, but cannot be handled in exactly the same way for two reasons, one being its much greater nuclear arsenal and the other being that it has a land border with a number of vulnerable states. The fact that its nuclear arsenal is very large, with a full spectrum of long- and short-range delivery systems, effectively protects it from any real risk of first strike, and this is a good thing both for Russia and the world. But its extensive land borders with potentially vulnerable states make the need for the big squeeze even more acute than for North Korea.

That is why the scale and nature of the civil and military aid going to Ukraine needs to be ratcheted up considerably, so that Ukraine can quickly drive out the invaders and can avoid being bogged down in another long-running hot stalemate. At this point, Russian nuclear posturing and the implied threat of strategic retaliation rings rather hollow.

And that is also why the regime of sanctions against Russia which has been triggered by its attack on Ukraine needs to be made as complete as possible, as soon as possible. It must become so total that it ultimately criminalizes on a near world-wide scale any commerce with Russia that has not been approved by a multinational body set up to review such matters. And it has to remain in place until an extensive list of conditions has been met. That list includes withdrawal from Ukraine, multi-year payment of reparations to Ukraine, trial and punishment of those individual perpetrators of war crimes who can be identified, and agreement to a long-term, gradual reduction in Russian nuclear capabilities, internationally verified, in exchange for very firm security guarantees solemnized by treaties.

It is to be hoped that such stages might be expedited, so that Russia and Russians could look forward in due course to economic and social progress. But the history of Russian duplicity does not automatically encourage one to imagine a rapid transition to legitimacy. If this sounds like it might involve keeping much of the pressure on for a couple of decades, well, if it is needed, so be it. Eventually, the world will be the better for it and, hopefully, the new Russia that emerges will be the better for it.

In the meantime, let us have a thought about the two nations that Russia and Pakistan imagined, incorrectly, that they were peer competitors of: the US and India, respectively. Despite their size, economic clout and defence preparation, they both need to be cautious about the risk of hubris. In recent years, both have experienced a decline in political health characterized by a decline in tolerance of and civility towards domestic political opponents, and an overall decline in respect for differences of opinion. It would be both ironic and a great shame if they accidentally began to adopt some of the unlovely features of the aspirants who thought they were their peers, but were not.

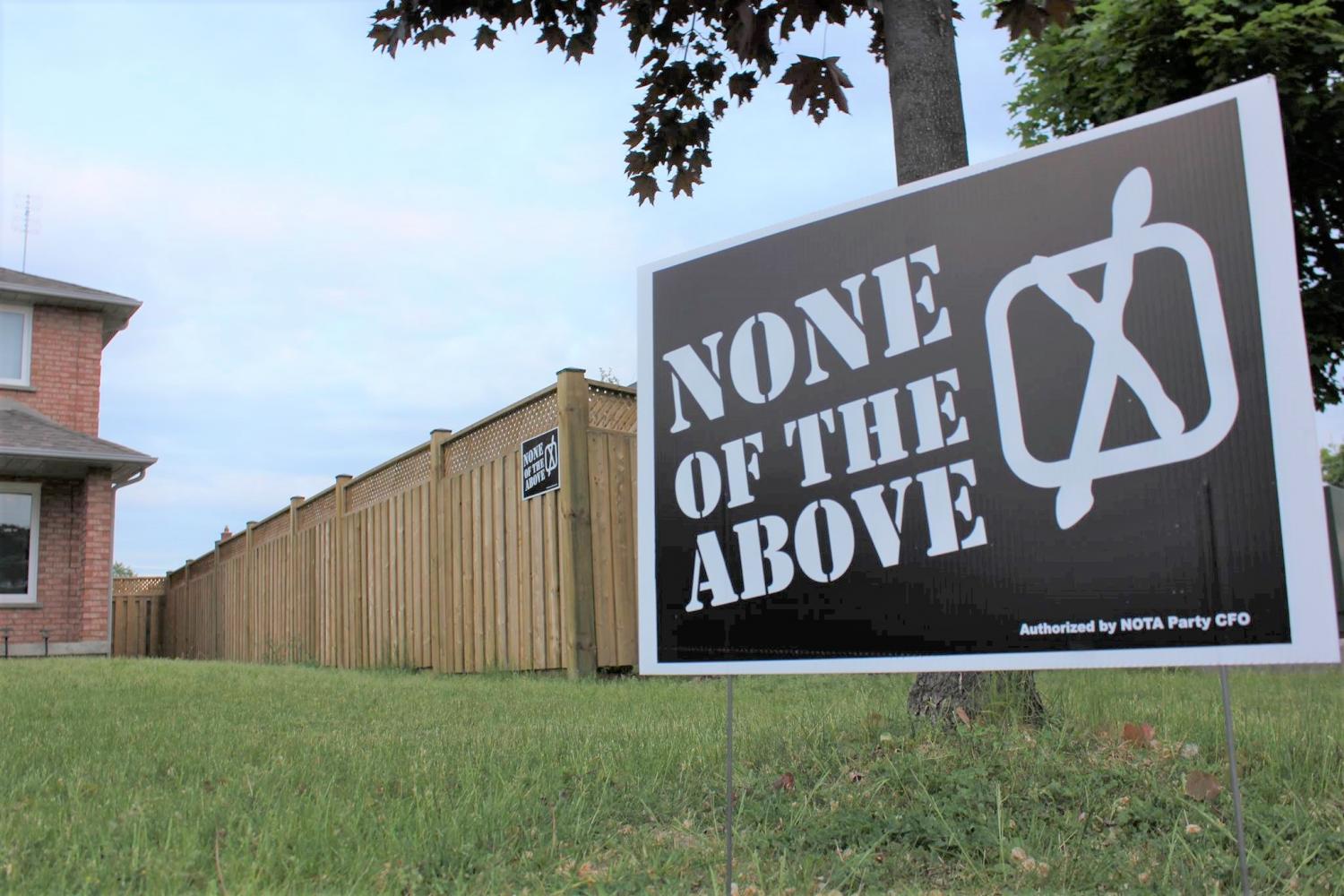

PHOTO: VIA CBC.CA