Equality for persons with disabilities on the line in new assisted dying legislation

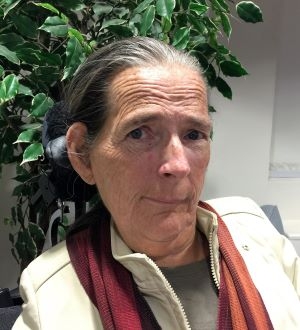

By Catherine Frazee

A consequential law is proceeding swiftly in Parliament, but mostly under the radar of Canadians with a lot on our minds these days.

Bill C7 will amend our current medical assistance in dying (MAiD) law by creating a separate pathway to assisted death for persons who are not dying and may have decades still to live, provided such persons have some form of disabling medical condition.

Bill C7 will guarantee their choice for medically assisted dying when suffering is intolerable, to forfeit whatever years of life remain, and to recruit a willing Canadian physician to cause their death.

As someone who has lived for 67 years with a degenerative medical condition, I am alarmed at how easily, when we are not paying close attention, a human rights norm can be toppled.

Bill C7 begs the question: WHY US?

Why only us?

Why make medically assisted dying easier only for people whose bodies are altered or painful or in decline? Why not everyone who lives outside the margins of a decent life, everyone who resorts to an overdose, a high bridge, a shotgun carried out to the woods? Why not everyone who decides that their quality-of-life is in the ditch?

Surely, loudly and clearly, the answer rises up in each of our throats. That’s not who we are. We dial 911, we pull you back from the ledge and yes, we restrain you in your moment of crisis, autonomy be damned. We will get to the heart of the problem that drove you out into the woods and we will beckon you back toward a life that is bearable.

Unless, of course, your suffering is medical or disability-related. Then, and only then, there will be a special pathway to assisted death. Death on demand, essentially.

Universality is the bedrock of our health care commitments. Why then does Bill C7 depart so radically, dropping the threshold for MAiD for one social group already known to bear the risk of suicide at rates well in excess of the non-disabled population, but not for others who suffer and die before their time?

What is it about disability that makes this okay?

And why such breathless confidence that Bill C7 will bring no harm to disability communities? Honestly, I do not know. But as we marshal our evidence for the legal challenges that will follow if this Bill is passed, this is what we hear in reply.

Some say that the suffering of a disabling medical condition is unlike other suffering, somehow more cruel than the overwhelming pain of any healthy, nondisabled person who turns to a premature death by suicide. But there is no evidence to support this ableist stereotype.

Some say that the suffering of disability defies all hope, as it did, they claim, for Jean Truchon, a man with cerebral palsy whose case before a Québec lower court paved the way for Bill C7. But the deprivations of institutional life that choked out his will to live were not an inevitable consequence of disability. Nor were the pandemic restrictions that curtailed all time with loved ones in the weeks prior to his final decision to die.

Did we learn nothing from Archie Rolland’s harrowing struggle, and his final cri de coeur, before assisted death: “It’s not the ALS that’s killing me.” Have we not heard the clear-eyed analysis of Scott Jones, who struggles with suicide every day, not because of paraplegia, but because “society disables me, isolates me and cages me in.”

Some say that the suffering of disabling conditions falls strictly in the domain of medicine. But the agonizing quest of Sean Tagert, who died by MAiD last August, teaches us otherwise. Tagert fought to the bitter end against the threat of transfer to an institution four hours away from the home where he cared for his 11-year-old son. He called the bureaucratic denials of needed home care a “death sentence,” just days before his assisted death.

Some fall back on the mantra of choice; they say that not everyone wants to “live that way.” But not everyone wants to live with the indignities of poverty either. No one wants to live under threat of racial or gendered or colonial violence. No one wants to live hungry, incarcerated, abject or alone.

Will our lawmakers carve out other shortcuts to assisted death for those who do live in such conditions or will you rise to the defence of human rights?

Of course, you will rise to the defence of human rights.

Now, I respectfully urge that you do the same for persons with disabilities, for with Bill C7, our equality is – right now – on the line.

Catherine Frazee is a Professor Emerita at Ryerson University, School of Disability Studies and Advisor to the Vulnerable Persons Standard.