Forty years later: who murdered Spike Dubs?

For most of us, it is a day of love and togetherness. But Valentine’s Day this year also marks a bleak anniversary in global diplomacy: a homicide that remains one of the most haunting cold cases of the Cold War.

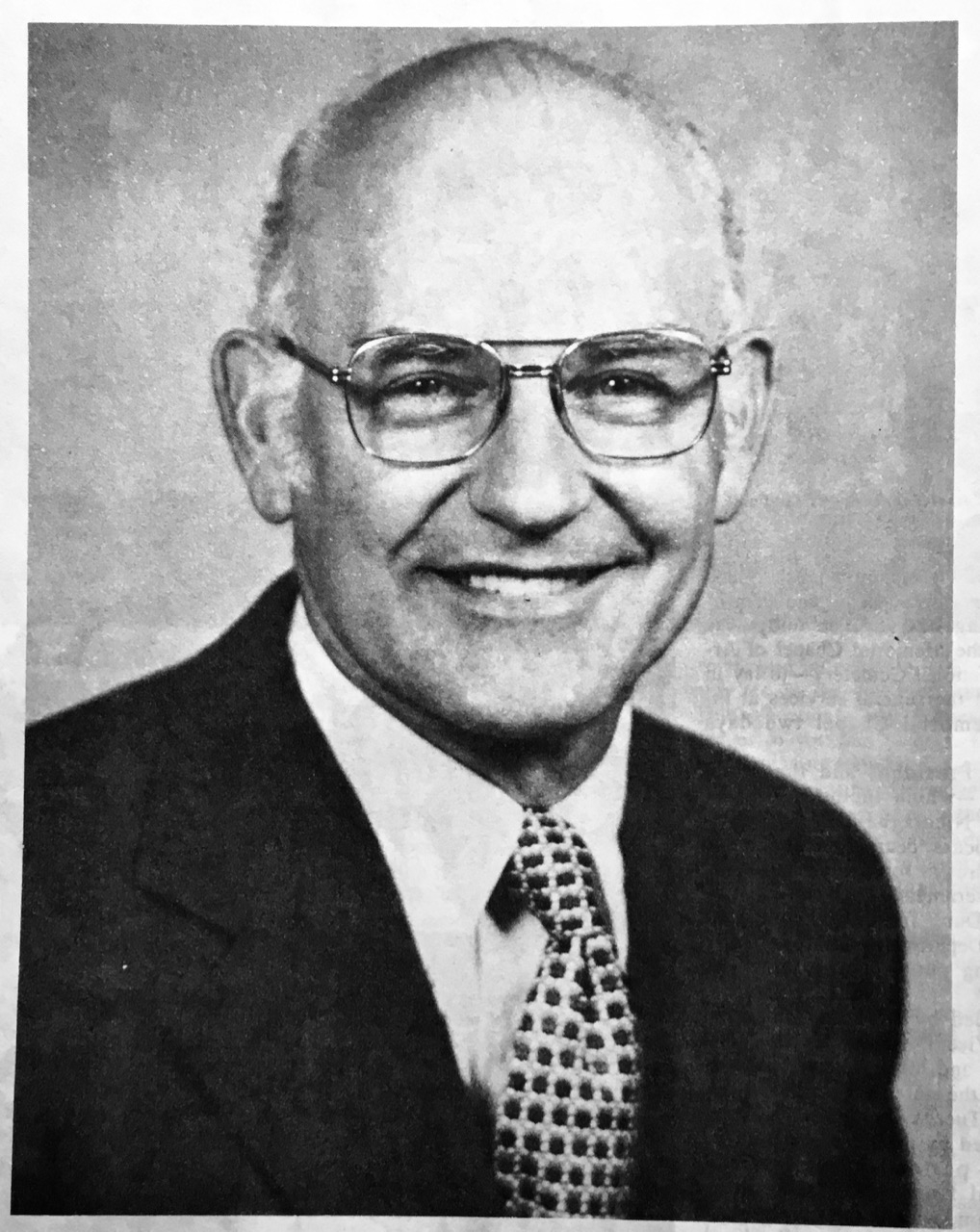

Forty years ago, on February 14, 1979, a seasoned, 58-year-old American foreign service officer, one of the U.S. State Department’s most respected ambassadors, got into his chauffeured Cadillac sedan on his way to work.

But Adolph Dubs – Spike Dubs to all who knew him – would never reach his office at the U.S. embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan. Stopped in traffic by a man wearing a police uniform, he was taken at gunpoint by the fake cop and three accomplices to room 117 of the nearby Hotel Kabul.

On the other side of the world in Washington, D.C., Spike’s 25-year-old daughter, Lindsay, was stirred from a deep sleep. “I received a phone call, somewhere in the middle of the night,” she says. “Mary Ann, my father’s second wife, called me. She was very upset. She said ‘oh, they’ve kidnapped your father.”

“That was stunning news to try to absorb – and of course we knew nothing.”

They were not alone. State Department officials who had broken the news were also in the dark. Communications with Afghanistan were tortuously difficult. And Spike’s embassy team in Kabul were receiving the opposite of assistance from the faction-ridden Afghan Communist regime that had seized power in a coup one year earlier in April, 1978.

“We didn’t have direct communications,” explains Doug Wankel, then a drug enforcement officer at the U.S. embassy. He was one of a dozen staffers who rushed to their ambassador’s aid at the hotel. Meantime, Dubs’ deputy chief of mission frantically tried to make contact with the Afghan regime leadership.

“It seemed that the people inside, as far as holding Ambassador Dubs, were not senior in whatever the group was that was behind this,” Wankel says. “These were people that were there to hold him, waiting for something else.”

That something has never been determined. The identities of the kidnappers, their motives and demands – all of this remains a mystery. Throughout the entire ordeal, U.S. officials were unable to establish direct contact with their Afghan regime counterparts, much less the kidnappers themselves.

Instead, as regime troops and police poured into the hotel, a trio of familiar figures appeared. Mike Malinowski, U.S. Consul in Kabul at the time, recalls: “Our people recognized them as coming from the KGB station in the Soviet embassy. They started to calm the Afghans down, which at first looked good, that somebody was in charge.” That reassurance was fleeting.

“We kept trying to get influence with the Soviets, saying for example that in our experience it’s very good in these types of situations to bring in professional negotiators and psychologists to try to effect a peaceful relief. But it was clear the Soviets didn’t want to get any advice from us.”

Spike Dubs was well known to the KGB operatives’ most senior bosses in Moscow. Following his first posting to Ottawa, Dubs’ Russian language skills placed him at the U.S. embassy in the Soviet capital during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. A decade later, he returned to Moscow as Chargé d'affaires. That post earned him regular, if not constant, surveillance by the KGB’s Seventh Directorate. By the time President Jimmy Carter posted Dubs to Afghanistan in 1978, he was well known to people like KGB chairman Yuri Andropov.

In Kabul, the Soviets’ intelligence column had their client regime “wired,” according to former C.I.A. officers working there at the time. Easily, the KGB would have been aware Dubs was a frequent visitor to the Communist regime’s foreign minister, Hafizullah Amin. The two met no fewer than 14 times by February of 1979.

Amin was fluent in English, having studied at Wisconsin and Columbia universities. This worried the Russians, as did Amin’s mercurial, egomaniacal nature. Just months later, KGB special forces troops murdered Amin and his family in the opening hours of the December, 1979 Soviet invasion.

Was Spike Dubs’ diplomatic relationship with Amin a factor in what happened at the Hotel Kabul? It is a lead that warrants investigation, particularly due to the actions of the KGB.

“The Russians made it clear,” Doug Wankel says, “they were there to take whatever action was going to be taken. No-one was talking to the Americans from the Russian-Afghan side to get ideas, opinions, thoughts, wishes; what we wanted.”

Malinowski says, “the Soviets were now totally in operational command of the units at the hotel.”

Then, four hours into the ordeal, just before 1 p.m. in Kabul, 3:30 a.m. in Washington, the senior KGB officer signaled to the troops. The door to room 117 was kicked open by a soldier in a flak jacket and Afghan Army uniform. He and two others rushed inside, assault rifles firing on full automatic. Five more soldiers opened up from the balcony of the bank across the street, spraying the room’s outer wall and window.

Some witnesses recall the barrage lasting 20 seconds, others say it was twice that long. When the shooting stopped, Wankel and Malinowski, with two colleagues, sprinted towards the room with a stretcher, their embassy doctor close behind.

“We wanted to get into that room as quickly as possible, and give the ambassador the best chance to get out of this,” Malinowski says.

But there was more gunfire: the sound of four pistol shots stopped them cold. Then, silence. They sprinted down the hall and entered the room.

“The gunsmoke was so acrid… you really couldn’t see,” Wankel says. Malinowski recalls blinding stumbling through broken glass.

“We stepped on two dead Afghans,” he says. “I literally stepped on them as we were going into the room. And then we looked and the ambassador was in a chair and slumped over. And the doctor was quickly onto him and I believe at that time, said, “Well, I believe the ambassador is dead.”

Dubs’ body and clothing would be the only physical evidence recovered by the Americans. An autopsy at Walter Reed in Washington found Dubs died of “at least 10 wounds inflicted by small caliber weapons.”

None of the weapons taken from the gang were produced for U.S. investigators. It would be three weeks before the regime permitted the Americans back into the room. By then it had been completely repaired. Bullet casings, clothing, personal effects – all evidence was disappeared by the regime and their Russian patrons.

Briefly, the Americans hoped one of the gang members would provide answers: they saw him captured alive when they first arrived at the hotel. But hours after the shooting, the prisoner’s corpse was put on display by the Afghan police for Malinowski and two colleagues, together with the bodies of the two men found in the room with Dubs – and a fourth cadaver, a mystery man.

The State Department’s final investigation report slated the Kabul regime’s account as “incomplete, misleading, and inaccurate,” in part because it made “no mention of the Soviets involved in the incident.” The report found the evidence established “serious misrepresentation or suppression of the truth” by the regime.

U.S. investigators concluded nine central questions remained unanswered, including: “What was the involvement of the Soviets in the decision making process” that led to the assault.”

Forty years later, our investigation is getting answers to the nagging questions hanging over this case. In addition to American eye-witnesses, we are interviewing every surviving participant we can find who was on the operational side of the action. And that begins with the former KGB officer who took charge at the Hotel Kabul.

Now 86, his has a ready response when asked who signaled the assault to commence. “Understand,” he says. “The order to shoot was given by the Afghans.”

Though contradictory, the answer fits a pattern that has emerged in the evidence. There is a chilling explanation for the old spy’s story. One we are determined to establish beyond doubt.

Arthur Kent’s reinvestigation of the case continues in the podcast series “Who Murdered Spike Dubs” at skyreporter.com