Photos: Suttershock.

In April 1915, standing on one of the First World War's deadliest fronts, Lt .Colonel Mustafa Kemal approached a group of soldiers planning to abandon their trenches. The young men of the 57th regiment were in the way of a large approaching force, and they were completely out of ammunition.

"You still have bayonets," said Kemal. "Affix them, and lie down."

"I do not expect you to attack," he continued. "I order you to die. In the time which passes until we die, other troops and commanders will take our place."

It's hard to imagine what those troops must have felt when they heard that order, but ignoring any fear they might have felt, they turned back towards the enemy and fought. None survived.

That enemy was a collection of Australian and New Zealand regiments who were eventually followed by soldiers from Newfoundland. The doomed men of the 57th regiment were Turkish soldiers fighting for the Ottoman Empire. In modern Turkey, their unit is legendary, but few Canadians have ever heard their stories. On December 9, 2015, Canadian Senator Anne Cools and the Council of Turkish Canadians held a conference on Parliament Hill titled the Great War and Gallipoli: A Reconstruction of Mindsets and Drives.

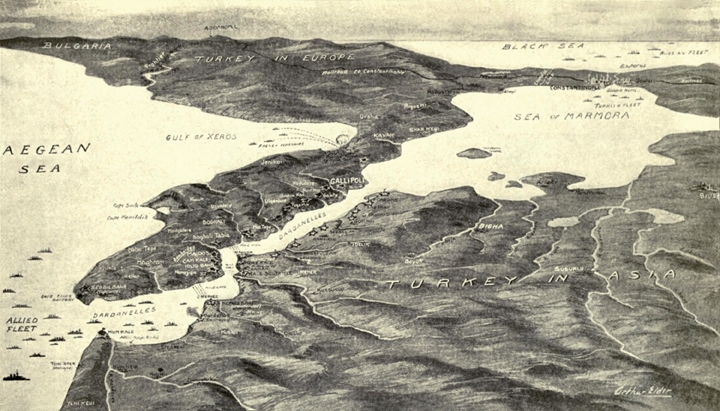

The Battle of Gallipoli, also referred as the Battle of Çanakkale, occurred on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey between April 25, 1915 and January 9, 1916. The British launched a naval attack followed by a mass landing in an attempt to capture the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The Turks repelled repeated allied attacks and pushed back the allied forces. Gallipoli became a defining moment in the establishment of a new Turkish regime as the charismatic Mustafa Kemal would use the hard won battle as part of his campaign to unite all Turks under one country from the tattered remnants of the collapsing Ottoman Empire. In Commonwealth Australia and New Zealand, citizens celebrate Anzac Day every April 25 to commemorate the battle. It surpasses Remembrance Day in terms of stature and importance.The British used those forces, and some from Newfoundland, like cannon fodder and thousands died. The battle has been immortalized in numerous movies and documentaries including Peter Weir and Mel Gibson's famous 1983 movie, Gallipoli, and in the heartbreaking 1985 Pogues song The Band Played Waltzing Matilda, which captures all its tragedy and horror in lead singer Shane McGowan's lyric: "and we buried ours and the Turks buried theirs, then it started all over again."

"The literature on Gallipoli from the British and Anzac (Australian and New Zealand) perspective is voluminous, but only a handful of narratives recount the Ottoman experience, "said Associate Professor Sevtap Demirci, one of the two Turkish historians who led the conference. Their goal was to show the often ignored Ottoman side of the battle and how the victory at Gallipoli led to Turkey's creation.

At the time of the battle in 1915, Newfoundland was still part of Britain. Soldiers from Newfoundland fought at Gallipoli and stayed to the bitter end.They suffered 49 losses, and when the attack was finally abandoned after eight disastrous months, their troops were some of the last to leave.

"It had a very significant impact on our community, which was very small," explained Newfoundland Senator Elizabeth Marshall at the event. "Fighting in the war was a family affair."

Today, we often blame the terrible losses on poor British planning, especially when it comes to the plans from leading Admiral Winston Churchill. But the real narrative is much more complicated than that. Blaming the loss on the British means we ignore the contributions and sacrifices of Turkish soldiers like the men of the 57th, who were fighting for their homeland.

"The Ottoman successes are largely attributed to the allied mistakes, the activities of German generals, or inhospitality of terrain," said Prof. Demirci.In short,the British give more credit to the ground the Ottoman soldiers were standing on than they give the people who fought and died. Naturally, the Germans also took the credit, saying that it was their officers stationed near Gallipoli that led the Ottoman soldiers to victory.

The victory at Gallipoli changed the Ottoman Turks forever. In fact, one Turkish official commented that "Gallipoli was the place where [the] Turkish nation started to breathe." In many respects, Gallipoli is to Turkey what Vimy Ridge is to Canada.

There is at least some truth to these points. The British absolutely did mishandle the invasion. Churchill planned the attack in four stages based around naval bombardment. He figured that when the long-range guns and minefields were gone the Ottomans would surrender as soon as allied boots hit the ground. But the Ottomans were more resilient than Churchill expected, and when the land invasion finally began in April, not even phase one of the four phase plan was complete.

Clearly, some of the blame lies with Churchill's poor strategy and the allies underestimating the defending Ottomans. But really, if it hadn't been for the Ottomans' unshakeable defence and willingness to die for their empire, they surely would have lost. The soldiers that did perish became heroes in the Ottomans' eyes, and the victory at Gallipoli changed the Ottoman Turks forever. In fact, one Turkish official commented that "Gallipoli was the place where [the] Turkish nation started to breathe." In many respects, Gallipoli is to Turkey what Vimy Ridge is to Canada. After all, our success at the battle of Vimy Ridge made our prime minister confident enough to push for more autonomy from Britain. In fact, the Turkish officer's quote sounds very similar to something a Canadian Brigadier-General said after Vimy Ridge: "in those few minutes, I witnessed the birth of a nation."

Winning Gallipoli came at a high cost for the Ottomans. Although more than 44,000 allied troops died during the eight month invasion, the Ottoman defenders lost nearly twice that many. More than 86,000 Ottoman soldiers lost their lives, and more than 150,000 were wounded. The two sides-trenches were often placed so close together that Ottoman and allied troops could talk and even trade some supplies, but that also led to very deadly fighting.

It's hard to imagine that anything new could emerge out of such a bloody and destructive conflict. But like new trees that grow out the ashes of a burned forest, new nations can begin from horrible battles and wars. The Ottoman Empire didn't survive the First World War, and there was even more blood and horror before Turkey emerged as its own nation.

Mustafa Kemal, the Lt. Colonel who ordered his disheartened soldiers to stay and fight even though they faced certain death, would later become the founding president of the new Turkish state. It was his split-second decision that saved the battle, and it was that battle that made his reputation, and eventually, his country.