How Canada Should Engage (Properly) with China’s Belt and Road Initiative

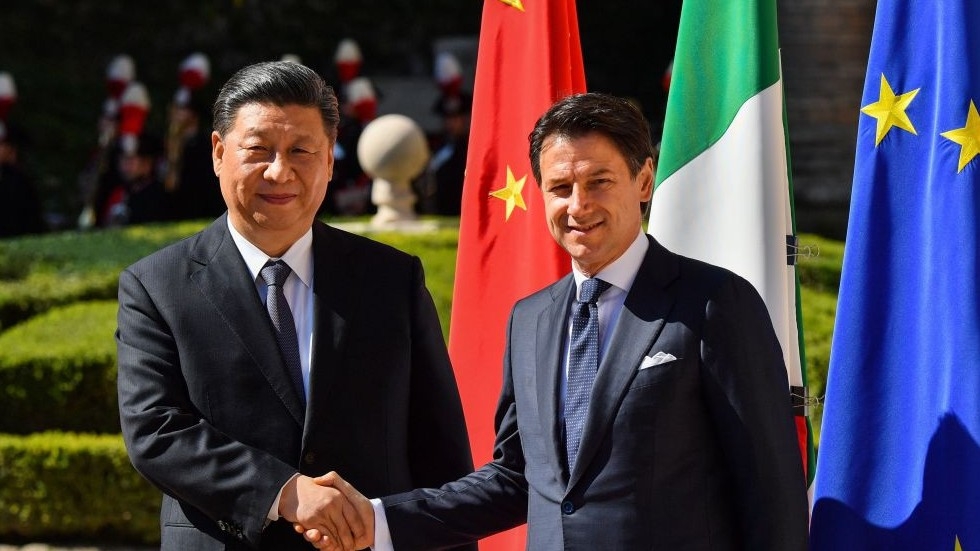

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is Chinese President Xi’s signature

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is Chinese President Xi’s signature

foreign policy plan and is one of the most ambitious infrastructure and investment

efforts in history. The BRI began in 2013 to boost trade through investment in

ports, power plants and other infrastructure in more than 140 countries from Asia

to Europe and Africa.

As trade wars between the U.S. and the rest of the world heat up, Canada should take this opportunity to reassess its trade relationships, particularly with China. An article by Preston Lim titled “What Ottawa Should Learn from China’s Belt and Road Initiative” offers one such perspective. After summarizing the scope of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the article denounces the potential debt traps and China’s unfair business practices. Ultimately, the author concludes that Canada should reject cooperating on the BRI in order to protest China’s practices in its “push for global power.” However, Lim’s article does not capture the whole picture regarding the BRI’s contributions to both developing countries and Canada itself. Thus, this article responds by illustrating similar national-interest driven behavior by Western states, acknowledging the necessity of Chinese loans, and offering concrete proposals for Canada to engage positively with China and the BRI.

The realist theory of international relations states that every major power, whether China or Western nations, enacts foreign policy and international business practices solely to pursue their own interests. Indeed, a glance at both history and current events demonstrates that the U.S. is no stranger to this behavior. As the issuer of the world’s foreign reserve currency as well as the largest stakeholder in institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the U.S. wields a de facto monopoly on the flow of global finance. More often than not, the U.S. has leveraged this advantage to benefit its own interests, specifically those of Wall St., at the expense of developing nations. The most obvious example would be the IMF’s role in causing the 1997 East Asia Crisis. As studied by Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book Globalization and its Discontents, the IMF pushed for capital account liberalization (opening domestic financial markets to foreign capital flows) in emerging East Asian countries such as South Korea and Thailand. Although these countries did not need outside finance thanks to their high domestic savings rates, the IMF (and by extension the U.S.) aggressively recommended further financial liberalization to supposedly “enhance macroeconomic stability.”[1] However, the exact opposite occurred when speculative loans from Wall St. flooded East Asia, fueling a debt bubble for local banks and private corporations. Once Western investors realized that these debts could not be repaid, they withdrew their money exactly when the Asian countries needed additional funds to weather the bubble’s collapse. By 1998, multiple countries (e.g. Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea etc…) had fallen into recession, resulting in spikes in unemployment and social discontent. Yet Wall St. emerged unscathed. Thus, Lim’s accusation that China practices “debt trap diplomacy” and breaks the rules of the Western liberal order is a convenient omission of the West’s own realist practices in leveraging its economic and political influence to serve its own interests.

In more specific terms, while Lim’s article correctly identifies debt distress as a concern regarding the BRI, it fails to acknowledge the necessity of Chinese loans for infrastructure in the recipient countries. According to a study conducted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2017, Asia needs to invest $26 trillion in overall national infrastructure between 2016 and 2030 to ensure “growth momentum, tackle poverty and respond to climate change.” However, the sum of the assets of all the major Western-backed Development banks (the World Bank, the ADB and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development etc…) only totals around $720 billion. In comparison, the combined assets of China’s two “policy banks” – the China Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM) and the China Development Bank (CDB) – total $2 trillion. Combined with the $100 billion and the $40 billion from the multilateral (but China-led) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund, respectively, Chinese loans represent one of the few, if not only, viable alternatives to help developing countries achieve their infrastructure goals.

Although some BRI recipient countries might balk at China’s supposedly unfair business practices, the reality is that the majority of these countries cannot convince the global financial system to invest capital in critical infrastructure. The Dushanbe-2 coal-fired power plant in Tajikistan exemplifies this market failure. Although the World Bank recommended in 2009 further investment in coal-fired power plants to ensure reliable electricity in the country, the lack of foreseeable financial return deterred most investors. In the end, it was the CHEXIM that provided most of the funding, with a loan of $331 million in 2010. When the power plant was completed in October, 2016, the Tajik government was soon able to lift daytime electricity restrictions, citing how the plant was now helping to provide uninterrupted power from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. each day. [2] Thus, the concrete benefits of this project demonstrates the need for Chinese contributions through the BRI, no matter how they are financed.

Instead of rejecting the BRI outright, Canada can take alternative routes to monitor and benefit from the initiative, namely by joining the AIIB and encouraging Sino-Canadian business partnerships. First, Canada’s application and eventual acceptance into the AIIB in March, 2017, was a step in the right direction. Since this institution will provide strong financial support to BRI projects, being a member country ensures that Canada can express its views on the initiative. The AIIB has already established a precedent for welcoming foreign expertise, as it partners with Western institutions, such as the World Bank, on almost all of its projects in order to learn best practices. By joining the AIIB, Canada can participate in vetting and overseeing projects to ensure the highest standards for funding and quality control.

American companies actually offer a model of how Canada can engage with the business side of the BRI without getting too involved in the politics. Yun Sun, a fellow in the Global Economy and Development department at the renowned Brookings Institution, penned an article in July, 2018 on how American companies are partnering with Chinese businesses in Africa on infrastructure projects. She cites the example of General Electric (GE) engaging with China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) to build a wind farm in Kipeto, Kenya and launching a “joint roadshow in Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Kenya, during which they showcased an in-depth market report on Nigeria’s grid system in response to challenges identified by the two companies in powering the country.” Sun writes that American companies see the BRI as a way to break into new markets in developing nations, while “the Chinese side has its eyes on GE’s ability to bring in advanced infrastructure industrial capacity, technological knowledge, and international financing channels.” In other words, GE’s case demonstrates how Canadian companies can spur growth and access emerging markets by participating in the BRI, even if the respective governments do not see eye-to-eye.

Canada’s strength lies in cooperation with other countries rather than confrontation. By engaging with China through its institutions and businesses, Canada can reap the benefits of the BRI while still actively addressing the initiative’s issues. With multilateralism in retreat around the world, Canada cannot afford to forsake its unique contributions to the BRI simply to make a political statement.

About the author:

Leo Luo is a graduate student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), majoring in Energy and Environment with a minor in East Asia studies. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from Georgetown’s Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service

Notes:

[1] Stiglitz, Joseph. Globalization and its Discontents Revisited. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018

[2] “Tajikistan Lifts Daytime Power Rationing.” BBC Monitoring Central Asia Unit. Last modified: January 5, 2017. Accessed: April 14, 2017. http://www.lexisnexis.

This article was first published by the Canadian International Council. We thank them for their cooperation.