Inuit Art: Traditional Yet Contemporary

At the 2017 Venice Biennale, an exhibition which shows the best contemporary art from around the world, Inuit artist Kananginak Pootoogook’s work was displayed.

It was a first for the Inuit art community.

Inuit art has been popular internationally for decades, but this was the first time it was included in the Venice Biennale.

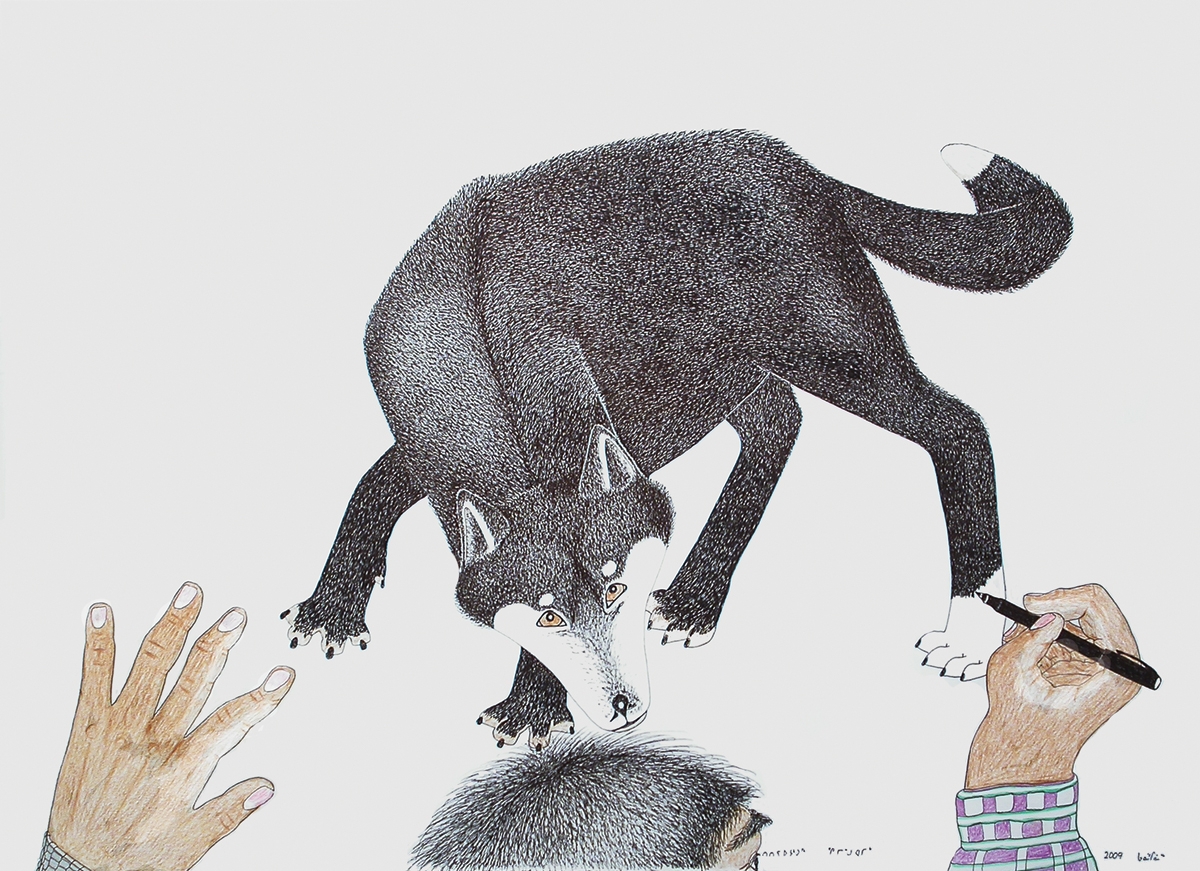

Ten of Pootoogook’s ink and coloured-pencil drawings were displayed alongside pieces by artists around the world.

The drawings depict Inuit life – the past and the present – including a successful walrus hunt, material cultures such as ATVs, and a self-portrait of the artist who is considered a household name in the Inuit art world.

As art historian and curator, Ingo Hessel writes in his book Inuit Art: An Introduction, contemporary Inuit art is a by-product of outside influences on Inuit culture, and its art is best understood in a historical and cultural context.

Before colonial contact, the Inuit people were semi-nomadic, split into regional groupings that relied on hunting for food, clothing, shelter and weapons.

Before colonial contact, the Inuit people were semi-nomadic, split into regional groupings that relied on hunting for food, clothing, shelter and weapons.

They told stories, played games and carved toys for their children. Inuit spirituality focused on the land and the animals, and Inuktitut, their language, purely oral until colonialists arrived, was “inseparable” from their culture, Hessel writes.

In the 1700s, Inuit people began trading with European and American whalers.

Inuit society was becoming increasingly dependent on trade and foreign goods.

Hessel writes that the Inuit were also affected by European missions, which offered medical assistance and education that undermined Inuit spirituality, language and other traditional knowledge.

Inuit art was also affected.

Artifacts had become a trade commodity alongside the burgeoning fur trade.

Inuit carvers began to make more delicate, display-only pieces, and as Hessel explains, European subject matter began to make its way into their carvings.

Hessel says the fur trade inextricably bound the two cultures together, allowing Inuit art to become an increasingly popular trade item.

After the collapse of the fur trade, Inuit carvers increased production of their art. A shift from ivory to stone brought new possibilities, including bigger carvings and different artistic styles.

“It was the absence of the fur trade that allowed (Inuit art) to fill the gap,” said Hessel. “It was truly a transitional time.”

The government pushed Inuit art production through companies like the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian Guild of Crafts. Inuit communities established artist co-operatives to support the growing industry, and the introduction of printmaking fostered a new artistic growth.

Of all the Inuit art co-operatives that sprung up during this time, perhaps the most well-known is the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in Cape Dorset, or Kinngait.

Pootoogook was instrumental in the founding of this co-operative in 1959, along with James Houston, who Hessel said is likely responsible for introducing printmaking to the Inuit people.

The co-operative is now the primary producer of Inuit prints and drawings.

“They really fostered creativity and originality and innovation,” said Hessel.

What really helped establish Cape Dorset’s Kinngait Studios as the hallmark of Inuit art production was the addition of its own wholesaler in 1978, Dorset Fine Arts, which operates out of Toronto.

Marketing manager William Huffman said having a southern outpost meant the co-operative could focus on art production while Dorset Fine Arts took care of liaisons with museums, galleries and other institutions. This includes the distribution of Cape Dorset’s renowned annual print collection, which artists work year-round to produce.

“Since the very beginning, (the collection) has been sort of the backbone of the studio’s activity,” Huffman explained.

The print collection is probably the most anticipated product to come out of Kinngait Studios, released every fall since the founding of the co-operative.

Through wholesalers galleries acquire Inuit art, often with the curatorial help of people like Paige Connell, who oversees prints and drawings at the wholesaler.

As well, wholesalers often have permanent collections that can be loaned to museums.

Older historical pieces are sold in art auctions, like the twice-yearly one that Hessel organizes for Walker’s Auctions. Several hundred pieces are showcased, which Hessel said he curates with as much care as if it were an gallery or museum exhibition.

The Galérie d’Art Vincent, located in the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa, has been acquiring and selling Inuit art for almost 25 years, indicated owner Vincent Fortier. Though they primarily sell sculptures, the gallery also sells the Cape Dorset print collection and drawings by some of the most well-known Inuit artists.

Marie-France Bouchard, who has worked at the gallery for more than two decades, said she has seen an increased interest in drawings recently.

Drawings were primarily made as proofs for prints, but are becoming a more popular medium for sale.

It isn’t just the mediums that have changed in Inuit art since the co-operatives were established. Contemporary Inuit work explores themes beyond what many expect from traditional Inuit art. Many of today’s Inuit artists, now into the third generation, draw scenes of daily Inuit life, or explore political themes such as climate change.

Annie Pootoogook, who died in 2016, used coloured pencils to depict everyday scenes like people watching television.

Her work also showed the harsher realities of life up North: scenes of alcoholism and abuse.

For the Inuit people, colonial contact resulted in a loss of tradition and culture that damaged societies, writes Hessel. Issues with violence, drugs and alcohol have increasingly become a theme as contemporary artists move toward depicting the truths of Inuit life.

For the Inuit people, colonial contact resulted in a loss of tradition and culture that damaged societies, writes Hessel. Issues with violence, drugs and alcohol have increasingly become a theme as contemporary artists move toward depicting the truths of Inuit life.

These artists are also gaining recognition beyond the Inuit art world.

Kenojuak Ashevak’s piece Owl Bouquet is shown on the commemorative "Canada 150" $10 bill, and Tim Pitsiulak designed a quarter in 2013 depicting a bowhead whale and two belugas.

Heather Campbell, an Inuit artist from Labrador, said people have come to expect a certain kind of art from the Inuit people – for example, the popular carvings of polar bears. However, she said that contemporary Inuit artists like Annie Pootoogook have challenged this.

Campbell worked as a curatorial assistant at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and helped curate the Canadian and Indigenous galleries at the National Gallery in Ottawa. She found herself learning about historical and contemporary Inuit art in a way that her university art education had not taught her.

“Seeing these contemporary artists bringing Inuit art into contemporary times really had a huge influence on me,” she said. Campbell, an oil painter originally, used to try and include traditional Inuit spiritual symbols in her art as a way of explicitly referencing Inuit culture. But she more recently began using a process where she draws with ink on top of colourful ink blots and lets her imagination find images in the colours.

“It’s become instinctive,” she said. “Whatever is in there comes out, and I’m okay with it.”

Campbell said, now she can explore traditional themes while also drawing upon the influence of her life in Ottawa. She said many contemporary Inuit artists are going down the same path – still portraying what it means to be Inuit, but in today’s world.

“Long ago, our art was for ourselves,” she said. “I think now, Inuit art is becoming more of a commentary on contemporary life.

“It’s going to change as our culture changes. We’re not living in a vacuum anymore.”