Invisible vulnerables: Persons with intellectual disabilities forgotten in the COVID-19 pandemic

By Eva Feder Kittay

I am hiding out in our lovely spacious house in the woods with my husband, hoping that COVID-19 will not find us. Both of us are in the “at-risk” category as we are both in our 70s. We are both New Yorkers, but we are upstate because our 50-year-old daughter lives in a community here.

Our daughter has a rare genetic condition which has severely limited her cognitive and motor abilities. She lives in a house with six other people, all of whom are medically fragile. An amazing and dedicated staff care for them.

For the last 18 years, we have brought her to our house on weekends where we play music, listen to symphonies, watch movies, do some physical therapy exercises, take long walks and enjoy the wonderful meals my husband loves to regale us with. Our son and his family sometimes join us, and our grandchildren have developed a beautiful relationship with their atypical, but sweet and very loving aunt.

Next weekend will be the third in a row when we have not visited her, and she has not come home with us.

As the novel coronavirus creeps its way from country to country, continent to continent, reminding us that as humans we share vulnerabilities and interconnections, we understand in a way we never have before that a harm to one can be a harm to all.

The reminder is stark and painful and is turning our world topsy turvy, giving us a surreal sense that we are living in a movie, in a virtual space, in anything but the world we know. The uncertainty, the timeline, the possible havoc it can wreak makes me think of the tsunami that washed away bartender, waitress, cleaning staff and happy tourists who were enjoying a day at a spectacular beach resort in Bali. I recall the picture of scores of vacationers and residents who stood at the edge of a beach watching in amazement as the water rushed back into the ocean before it returned with a force that swept them and thousands upon thousands away with its stunning force.

Today, I feel as if we are sitting on that sand beach watching and waiting for a tsunami.

We hear a lot about the vulnerable elderly, people in nursing facilities, in prisons, those who are fighting cancer or heart disease — conditions that weaken the body’s ability to fight the invading virus. For, in truth, that is all we have — our immune systems, as we await a cure and vaccine.

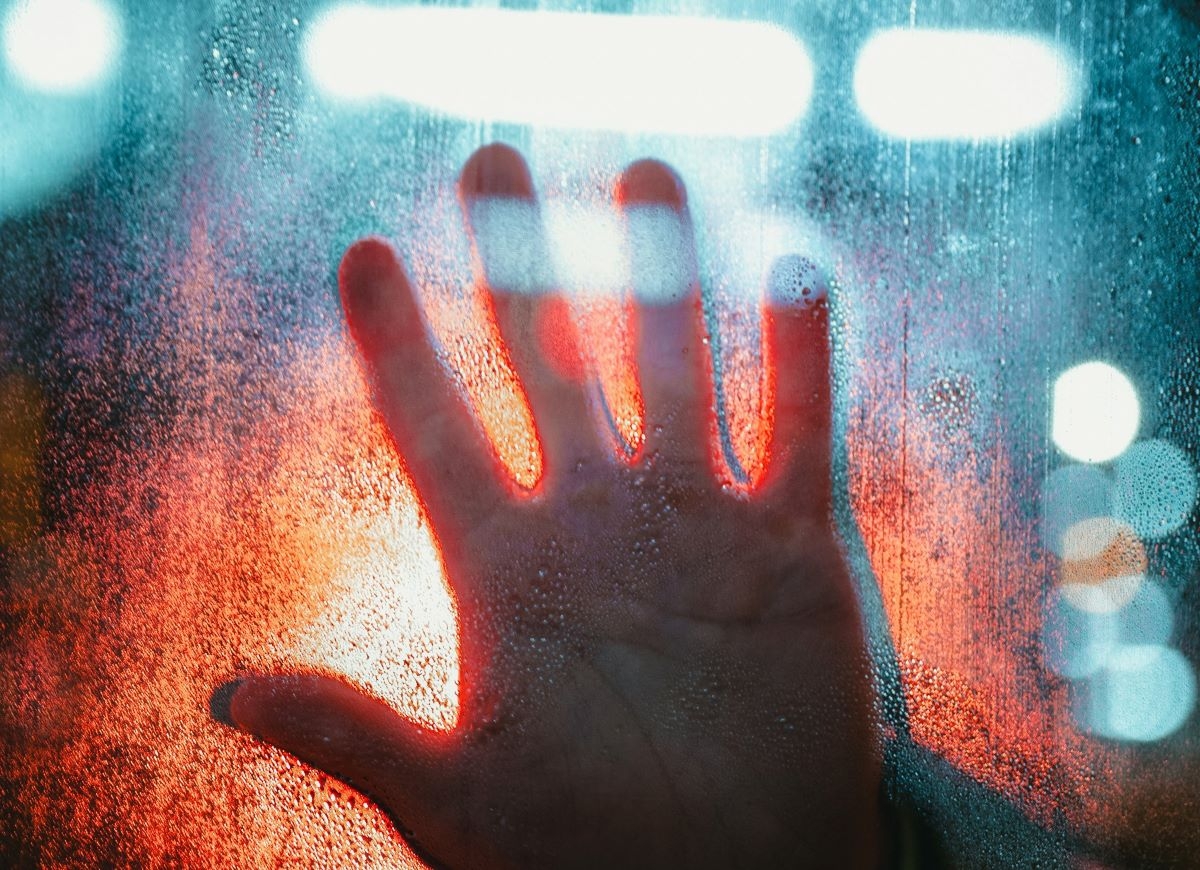

But one group of vulnerable people are rarely mentioned. People with disabilities and people whose disabilities ordinarily require a very high level of care: people like my beautiful daughter. For these folks, there is no possibility of social distancing. Most would perish in a matter of days if left alone. For many, touch is the most powerful form of communication.

They remind us daily of our dependence and interdependence, of human frailty and precariousness.

I might be able to explain to her why we cannot visit — why we can send only virtual kisses, not the close mushy ones she loves best. But I would not know if she understood. In likelihood, she would understand bits of it, but it would give her no coherent sense of what is happening in the world, and why suddenly what is occurring globally means she cannot come back to mom and dad on weekends, and why we are prevented from even visiting her in her house.

I feel enormous sadness for the millions and millions who will have their lives tragically disrupted by death, illness, loss of income and loss of dreams. I cannot comprehend how this could happen, much less happen in the United States.

Most of all, I cannot help but fear for my daughter, for the people who live with her and those who are similarly situated. Not only must they meet the tsunami with frail bodies, they face an additional foe: the failure to recognize and value their lives. The failure to speak of this vulnerable group is already an indication of how little they seem to matter to people.

Those who know people like my daughter have to make their faces, their smiles, their beauty and love known to others. For those of us fortunate enough to have such a person in our lives, we know the treasure we have been granted.

When you speak of the vulnerable, those most likely to suffer worst from this virus, think of grandma and grandpa, of uncle with the weak heart, the migrant in a crowded detention centers, the prisoner — but think also of those who live graceful lives of love, people like my daughter.

Eva Feder Kittay is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Philosophy at Stony Brook University/SUNY. Her pioneering work interjects questions of feminism, care and disability (especially cognitive disability) into philosophy. Her latest book, Learning from My Daughter: The Value and Care of Disabled Minds (Oxford University Press, 2019) was award the PROSE prize for the best book in philosophy in 2020.

Photo: Josh Hild, Pexel