Is Liberalism Dead in Canada?

On election night in my area of North Toronto, the cold days that dominated most of April were finally being driven out by the warm gusts of spring. Perhaps that is why few people noticed the gusts of change that were about to sweep across the Canadian political landscape. Everyone knew the conservatives would win, but the expectation was that Canada would likely enter another minority parliament. The Bloc might suffer at the expense of the NDP, but would still retain its dominant status within Quebec. And at the end of the night the liberals, for all their misfortunes, would still seem like the only likely alternative to Harper’s conservatives. The early tallies did little to alter this overall impression. The conservatives were leading from the word ‘go,’ but the liberals and NDP remained close in terms of projected seat counts. Among the first early signs that something was amiss for the liberals was the early lead assumed by conservative Bernard Trottier over Michael Iganatieff. The race was very close but as more votes were counted the gap widened just enough that it was clear Ignatieff would lose his seat after holding it for only one parliament. Other developments were equally ominous for the party. Long time Liberal MPs who once easily held their respective ridings – Ken Dryden, Joe Volpe, among many others – were suddenly on the losing end of races. Their long term presence in the House of Commons was once a source of stability; on this night, it had become a liability. Many younger liberals – Gerard Kennedy among the most prominent – fared no better. Liberal urban heartlands were, by the end of the evening, liberal urban wastelands.

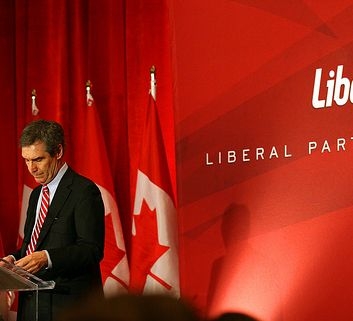

Indeed, what was most striking was the sense by the evening’s end of a party that suddenly seemed antiquated, as though the rest of the country had passed them by. Not surprisingly, party members were stunned. Michael  Ignatieff spoke that night with subdued passion and conviction. But for all its strengths, his speech also conveyed bewilderment, as though he couldn’t begin to explain what had just happened, why Canadians didn’t warm to him or why the party that dominated Canadian politics for so long could only win 34 seats in a 308 seat parliament. This impression was fuelled by visuals. The jet black backdrop in a room that was half empty made it seem as though he was speaking at a funeral and not at a political event. The few people there could scarcely contain their mix of disbelief and despair. They too were no doubt wondering how a liberal campaign could have gone so spectacularly wrong.

Ignatieff spoke that night with subdued passion and conviction. But for all its strengths, his speech also conveyed bewilderment, as though he couldn’t begin to explain what had just happened, why Canadians didn’t warm to him or why the party that dominated Canadian politics for so long could only win 34 seats in a 308 seat parliament. This impression was fuelled by visuals. The jet black backdrop in a room that was half empty made it seem as though he was speaking at a funeral and not at a political event. The few people there could scarcely contain their mix of disbelief and despair. They too were no doubt wondering how a liberal campaign could have gone so spectacularly wrong.

The post election hand wringing has seemingly only confirmed that the liberal party is adrift with no sense of direction. Although there is constant talk of the need for ‘renewal,’ party members seem deeply uncertain as to what this process might mean. What’s worse, there remains internal disarray and in fighting. Some party members would like a leadership convention sooner rather than later. Others, such as Jean Chretien, insist that Harper’s majority gives the party the luxury of time. Meanwhile both Bob Rae and Carolyn Bennett publicly expressed their displeasure with the party executive’s silly determination that any interim party leader will not be able to run in the actual leadership race. Their leadership problems run deeper. Historically one of the party’s strengths was the number of quality people who many could imagine as leader and prime minister. Now, by contrast, there is an utter dearth of obvious choices. Some even question if the party has a future.

Not all of the post election analysis has been doom and gloom. Some party members and pundits correctly note the role of vote-splitting in securing the conservative majority. Minimize the splitting, the thinking goes, and Harper will have a harder time next election winning so many seats, particularly in Ontario. The vital role of leadership has also been emphasized. The right leader, possibly young and charismatic, will lift the entire party’s fortunes. Yet it was widely believed that Ignatieff would prove more effective than his immediate predecessor, Stephane Dion, and couldn’t possibly do any worse. Of course, he did much worse! Could it be then that the liberal’s woes reflect a more fundamental shift in the country’s politics? Could it be that the party’s miserable election outcome, its internal disarray and the questions surrounding its future are symptomatic of a deeper crisis for liberalism as a political philosophy?

Not all of the post election analysis has been doom and gloom. Some party members and pundits correctly note the role of vote-splitting in securing the conservative majority. Minimize the splitting, the thinking goes, and Harper will have a harder time next election winning so many seats, particularly in Ontario. The vital role of leadership has also been emphasized. The right leader, possibly young and charismatic, will lift the entire party’s fortunes. Yet it was widely believed that Ignatieff would prove more effective than his immediate predecessor, Stephane Dion, and couldn’t possibly do any worse. Of course, he did much worse! Could it be then that the liberal’s woes reflect a more fundamental shift in the country’s politics? Could it be that the party’s miserable election outcome, its internal disarray and the questions surrounding its future are symptomatic of a deeper crisis for liberalism as a political philosophy?

One of the defining features of Canada’s political landscape in the 20th century was the dominant role of both Quebec and Ontario in federal politics. Liberal majorities more often than not were won in Quebec and Ontario. The vital importance and role of the two provinces is typically attributed to the high number of seats found in both. Quebec has 75 seats, Ontario 106. More fundamentally, however, the dominant role of the two provinces was a function of the economy. Both were manufacturing heartlands, the basis of Canada’s economic development and strong rates of economic growth throughout much of the last century. Liberalism thrived largely because the economy made it possible for it to do so.

Quebec and Ontario’s shared dominance produced its own echoes throughout western Canada. Throughout much of the last century Alberta’s resentment towards Central Canada festered. Alberta’s political establishment in particular took exception to their limited role in national politics and to intrusions into their own provincial affairs. Equally important was the gradual emergence of a different set of ideological priorities. Most Albertans thought the Canadian state was too expansionist and committed to programs that were too costly. Taxes were too high. Liberalism, from the perspective of many in the west, was the problem with how the country was governed. This was the impetus fuelling the formation of the Reform Party, the Conservative-Alliance Party and finally the revived conservative party under Stephen Harper. They have spent years maneuvering their way towards power in Ottawa. Their efforts have been aided by Canada’s altered economic landscape. Ontario and Quebec’s manufacturing base has withered. Alberta in particular is, of course, rich in oil, a limited resource that more and more of the world needs.

towards Central Canada festered. Alberta’s political establishment in particular took exception to their limited role in national politics and to intrusions into their own provincial affairs. Equally important was the gradual emergence of a different set of ideological priorities. Most Albertans thought the Canadian state was too expansionist and committed to programs that were too costly. Taxes were too high. Liberalism, from the perspective of many in the west, was the problem with how the country was governed. This was the impetus fuelling the formation of the Reform Party, the Conservative-Alliance Party and finally the revived conservative party under Stephen Harper. They have spent years maneuvering their way towards power in Ottawa. Their efforts have been aided by Canada’s altered economic landscape. Ontario and Quebec’s manufacturing base has withered. Alberta in particular is, of course, rich in oil, a limited resource that more and more of the world needs.

This gradual shift westward in economic power has had various long term consequences, some of which account for the waning appeal of liberalism and for the liberal party’s malaise. Governments, we are told, can no longer assume an active role in meeting important social challenges. For doing so might require taking on a deficit or worse, increasing taxes. Any policy initiative that might require increasing taxes is immediately characterized as irresponsible and unaffordable. Stephane Dion’s proposal in 2008 to use a taxation scheme to combat climate change was ruthlessly – and successfully – pilloried by the conservatives. This election, Michael Ignatieff’s promise to rescind the conservative’s last round of corporate tax cuts was similarly dismissed. Liberalism hasn’t been able to withstand the strain to which it has been subject. And the liberal party hasn’t figured out how to successfully challenge the prevailing economic wisdom the conservatives keep preaching to Canadians. Until they do, the party’s fortunes are not bound to improve.