On election night in my area of North Toronto, the cold days that dominated most of April were finally being driven out by the warm gusts of spring. Perhaps that is why few people noticed the gusts of change that were about to sweep across the Canadian political landscape. Everyone knew the conservatives would win, but the expectation was that Canada would likely enter another minority parliament. The Bloc might suffer at the expense of the NDP, but would still retain its dominant status within Quebec. And at the end of the night the liberals, for all their misfortunes, would still seem like the only likely alternative to Harper’s conservatives. The early tallies did little to alter this overall impression. The conservatives were leading from the word ‘go,’ but the liberals and NDP remained close in terms of projected seat counts. Among the first early signs that something was amiss for the liberals was the early lead assumed by conservative Bernard Trottier over Michael Iganatieff. The race was very close but as more votes were counted the gap widened just enough that it was clear Ignatieff would lose his seat after holding it for only one parliament. Other developments were equally ominous for the party. Long time Liberal MPs who once easily held their respective ridings – Ken Dryden, Joe Volpe, among many others – were suddenly on the losing end of races. Their long term presence in the House of Commons was once a source of stability; on this night, it had become a liability. Many younger liberals – Gerard Kennedy among the most prominent – fared no better. Liberal urban heartlands were, by the end of the evening, liberal urban wastelands.

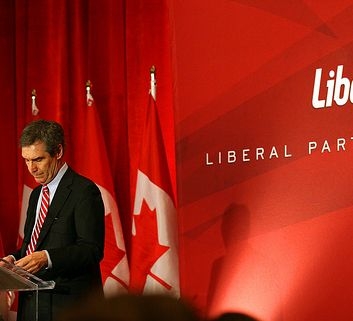

Indeed, what was most striking was the sense by the evening’s end of a party that suddenly seemed antiquated, as though the rest of the country had passed them by. Not surprisingly, party members were stunned. Michael

The post election hand wringing has seemingly only confirmed that the liberal party is adrift with no sense of direction. Although there is constant talk of the need for ‘renewal,’ party members seem deeply uncertain as to what this process might mean. What’s worse, there remains internal disarray and in fighting. Some party members would like a leadership convention sooner rather than later. Others, such as Jean Chretien, insist that Harper’s majority gives the party the luxury of time. Meanwhile both Bob Rae and Carolyn Bennett publicly expressed their displeasure with the party executive’s silly determination that any interim party leader will not be able to run in the actual leadership race. Their leadership problems run deeper. Historically one of the party’s strengths was the number of quality people who many could imagine as leader and prime minister. Now, by contrast, there is an utter dearth of obvious choices. Some even question if the party has a future.

One of the defining features of Canada’s political landscape in the 20th century was the dominant role of both Quebec and Ontario in federal politics. Liberal majorities more often than not were won in Quebec and Ontario. The vital importance and role of the two provinces is typically attributed to the high number of seats found in both. Quebec has 75 seats, Ontario 106. More fundamentally, however, the dominant role of the two provinces was a function of the economy. Both were manufacturing heartlands, the basis of Canada’s economic development and strong rates of economic growth throughout much of the last century. Liberalism thrived largely because the economy made it possible for it to do so.

Quebec and Ontario’s shared dominance produced its own echoes throughout western Canada. Throughout much of the last century Alberta’s resentment

This gradual shift westward in economic power has had various long term consequences, some of which account for the waning appeal of liberalism and for the liberal party’s malaise. Governments, we are told, can no longer assume an active role in meeting important social challenges. For doing so might require taking on a deficit or worse, increasing taxes. Any policy initiative that might require increasing taxes is immediately characterized as irresponsible and unaffordable. Stephane Dion’s proposal in 2008 to use a taxation scheme to combat climate change was ruthlessly – and successfully – pilloried by the conservatives. This election, Michael Ignatieff’s promise to rescind the conservative’s last round of corporate tax cuts was similarly dismissed. Liberalism hasn’t been able to withstand the strain to which it has been subject. And the liberal party hasn’t figured out how to successfully challenge the prevailing economic wisdom the conservatives keep preaching to Canadians. Until they do, the party’s fortunes are not bound to improve.