King is Dead, Long Live the King: The Political Cartoons of Josh Silburt

The irreverent tenor of Josh Silburt’s art echoes through the historic site that used to house former Prime Ministers Wilfred Laurier and Mackenzie King.

Josh Silburt was a political cartoonist during the mid-20th century, and his work is currently exhibited in Laurier House (335 Laurier Avenue). His caricatures spanned the Second World War, the emerging labour movement, and the start of the Cold War. Serving as Canada’s tenth Prime Minister, Mackenzie King was a central target for the artist’s sardonic commentary. Erecting an exhibit in King’s old home makes for a playful and 3-dimensional look at the former Prime Minister. Canadian history may be written by the victors, but it was critiqued by their witty contemporaries.

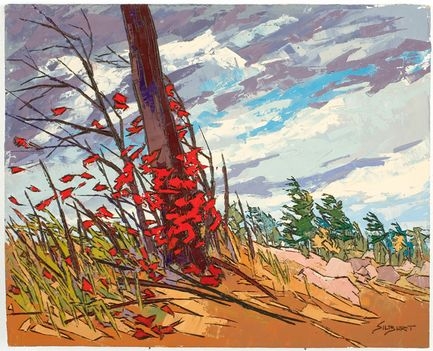

Allan Silburt is the curator of his father’s artistic legacy, the custodian of the remarkable work the artist left behind. He has been setting up these exhibitions in the spaces his father lived and worked so as to let them speak as vibrantly as possible. The exhibit in Laurier House is one of several targeted exhibitions and contains both his political cartoons and his landscape paintings.

“This was the first time I targeted the content,” explains Allan, enthusiastically. “So, shaping an exhibit like this, the one thing that holds it together is Mackenzie King. What I came up with was not so much a chronology as a topic, a series of things that Canada was dealing with at the end of the war.”

The trajectory of Josh Silburt’s life was and still is historically resonant. Having spent his formative years in the Great Depression, Silburt’s life spans the length of a tumultuous century in Canadian history. His career as a cartoonist played out over the complicated backdrop of his politics. A self-identifying Communist, Josh Silburt’s political views leaned hard to the left, and he was far from alone. Communism at that time was a well-supported viewpoint, with a great deal of representation. It did however make it hard to keep a job in mainstream media, and Silburt struggled to reconcile his personal views with a career that sometimes demanded compromise.

The trajectory of Josh Silburt’s life was and still is historically resonant. Having spent his formative years in the Great Depression, Silburt’s life spans the length of a tumultuous century in Canadian history. His career as a cartoonist played out over the complicated backdrop of his politics. A self-identifying Communist, Josh Silburt’s political views leaned hard to the left, and he was far from alone. Communism at that time was a well-supported viewpoint, with a great deal of representation. It did however make it hard to keep a job in mainstream media, and Silburt struggled to reconcile his personal views with a career that sometimes demanded compromise.

Deeply ingrained in the events of his time, Silburt’s cartoons, arranged so well by his son, bring an entire historical scene back to life. But not only does the exhibit frame the 20th Century in a refreshing new light, it also pulls it’s own commentary into the present. Somehow, the reverberations of Silburt’s art reach all the way into 2018 and surprise the viewer with their relevance.

“There are a couple things that I think make it relevant today,” says Allan. “First of all the issues themselves. A lot of the issues we deal with in general are a bit transcendent — the goal of a government is to distribute wealth and to deal with the problems that a country faces, and those problems are, to some extent, perennial. He talks about high prices and low wages, a lot of the working man’s perspective, and it’s easy for people to relate to that.” The act of criticizing one’s government also, to a degree, transcends time. Dismantling the country’s wartime structures after the Second World War meant an unravelling of economic systems and labor relations, all of which are topics we debate today. “All these things still resonate,” says Allan, “and so does the ‘common man’ perspective.”

Silburt’s cartoon career was blossoming around the same time as the emergence of comic books. His drawing style, quite characteristic of the graphics of the period, in some ways lives on quite vividly in an entire literary form. “The business of cartoons in that time was to empower the common man,” explains Allen. Given the volatility of international politics, national labor relations, and a quickly changing economy, caricature drawings and comics were a popular method of advertising during Silburt’s time. They pushed citizens to participate, to be active, to vote, by pushing the boundaries of our visual reality. The drawing style has been recreated so often since then that a meander through the Laurier House exhibition feels both profoundly historical and eerily contemporary. The result is a spectacularly stimulating critique on Canada, both then and now.

“I’m not an art historian, but I’m an expert on his art.” says Allan, describing his favourite pieces of his father’s work. “The cartoon of the balancing scales with the Canadian dollar on one side and the American on the other is one of my favourites. Another one is the illustration of Ottawa’s bureaucracy.” This second cartoon comments on the rising number of civil servants after the end of the second world war. On the comically overblown desk behind which three men are stacked is a thick roll of “red tape”. This cheeky literalization of the capital city’s bureaucracy is the perfect example of how Silburt’s images stand the test of time.

In the creation of this exhibit, Allan Silburt partnered up with Debra Antoncic, a curator he had worked with before on an exhibition in the Riverbrink Art Museum in Niagara-on-the-Lake. The museum used to house a very large Silburt exhibit; nearly the whole building was given over to Josh’s artwork. The artist had worked for the Saint Catherine's Standard for several years during the Depression, and the exhibit was therefore able to celebrate one of the area’s local heroes.

The truest way to participate in your present is by speaking up; Josh Silburt combined his witty observations with his extraordinary artistic talent and sense of humour, and his work is now one of the most interesting windows into Canada’s 20th Century. The Mackenzie King exhibit will be at Laurier House until September 3rd, and admittance is free! Check out the exhibit while you still can, read Allan Silburt’s book, A Colourful Life, about his father, or visit his website to learn more.