Mobile Technology Is Changing the Face of Health Care

This was the first thing that caught JoAnne Sutch’s attention when she entered a walk-in clinic last November. Instead of a piece of paper and a clipboard, she was offered a tablet computer to enter her medical information. Many educational facilities such as devry university health information technology include curriculum that incorporate new technology. When she was finally seen, even her doctor was consulting one of the hand-held devices.

Soon, this kind of practice may not be so unusual. The use of mobile technology is a growing trend in the medical industry. According to a 2012 report by industry analysts Frost and Sullivan, the mobile health market in the United States earned US$230 million in 2010, and the study estimates that there will be 82 million tablet users in the country by 2015, up from 10 million in 2010.

In Canada, mobile devices are used for everything from ordering X-rays, to recording vital signs and reading results – all at the patient’s bedside. Almost every day, applications are being developed for these new portable platforms.

However, with such an avalanche of new technology, big rewards bring big risks. Teams of programmers and IT professionals are putting a strain on an already stretched health-care budget, and critics have raised concerns over the effect the additional screen time might have on the relationship between doctors and their patients.

Is Canada ready for an electronic health revolution?

“It’s a fact that we have to deal with, whether we like it or not,” said Dr. Avi Parush, a psychology professor at Carleton University who has done research on communications and health- care professionals. “The use of mobile devices is becoming very, very pervasive. You see people in the middle of the emergency room, operating room and ICU, taking out their mobile device and checking for guidelines and such.”

For example, the Ottawa Hospital has deployed over 3,000 tablets to its doctors and nursing staff since starting an experimental program in 2010. It is the largest installation of medical tablets on the continent, the hospital reported.

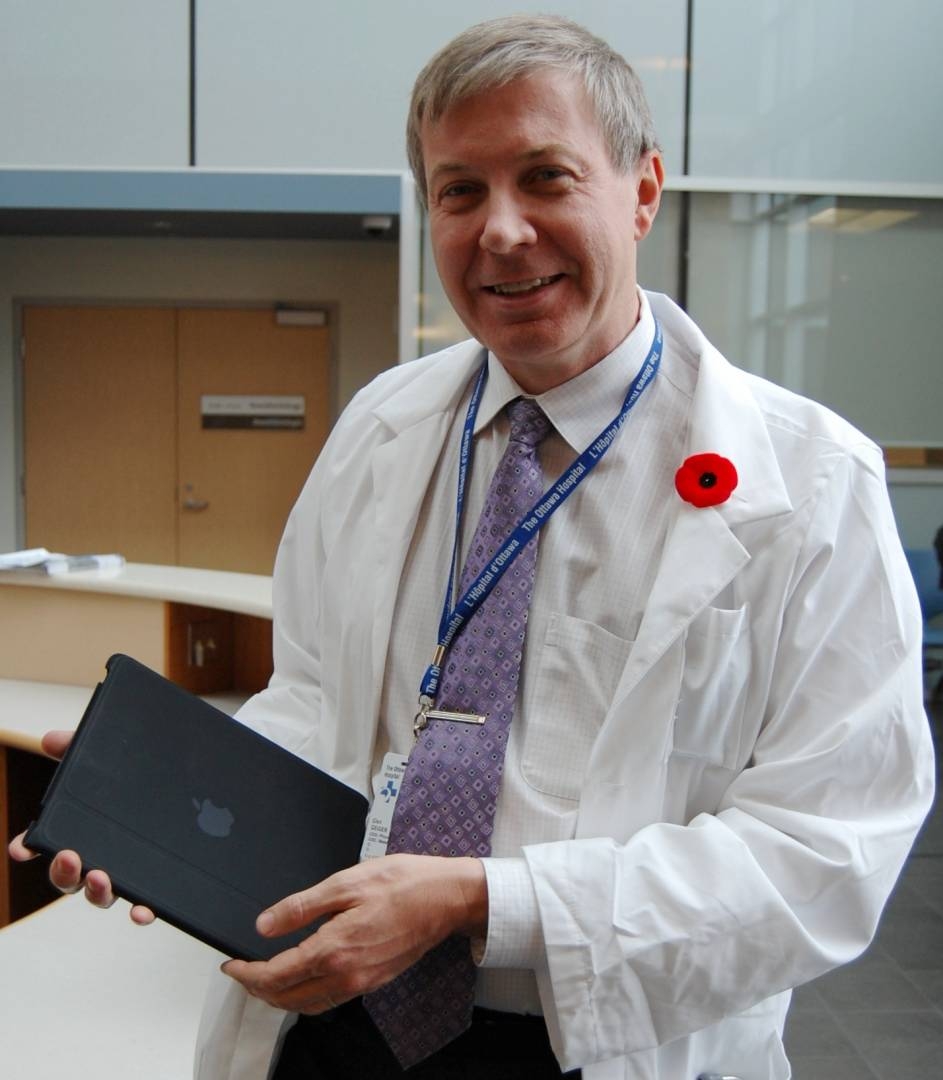

The overall response has been very positive. Doctors are excited about the new possibilities for medical practice. Tablets eliminate the need for paper charts and frequent visits to nursing station computers, said Dr. Glen Geiger, chief medical information officer at The Ottawa Hospital.

Geiger said that before the hospital started using iPads, daily rounds consisted of sitting down with a team of doctors and talking about the patients, without actually seeing them. With the addition of tablets, doctors now have more time to discuss results with the patient as time spent going back and forth from nursing station computers to printing results has been drastically reduced.

“It’s much better,” said Geiger. “The patient sees everybody. Patients appreciate being told their current information; they appreciate seeing their own X-rays; and they appreciate the quality of information they’re getting. They’re more informed and therefore, they’re getting better control of their health care.”

However, in a 2011 study on patient confidence done by the journal Canadian Family Physician, 27 per cent of patients surveyed responded negatively to their doctors accessing medical information on a personal digital device. Those patients indicated that as a result, they felt less confident in their doctor and believed they were getting a lower quality of care. Another study, completed in 2006 at the University of Toronto, showed that doctors are also concerned about how using a mobile device affects their credibility as physicians. Many felt that using a device in front of patients seemed rude or impersonal.

“The face-to-face encounter has a lot of power,” said Parush. “The personal contact builds trust between the physician and the patient, and is a critical component in the whole healing process.”

“Sometimes you don’t even talk to the medical receptionist,” said Sutch about her experience with the clinic. However, she was less concerned with the lack of face time and more with the potential security risk. Sutch felt that with the tablet being passed around clinic employees, it could fall into the wrong hands.

“My concern was – ‘Do they put it down, and is it visible to other people?,’” said Sutch. “If I know how to use an iPad, why wouldn’t I be able to just start looking?”

Confidentiality is one of the main reasons new users are reluctant to adopt the technology, according to the same 2012 report on mobile health by Frost and Sullivan. “The realm of health information is so fraught with emotion and liability that the effects of security gone awry are all the more upsetting and may restrain wider mHealth adoption,” the report stated.

Additionally, the number of health care-related data breaches in the US rose by 97 percent between 2010 and 2011, according to a recent survey conducted by US medical technology publication GovernmentHealthIT. Geiger and his team took steps to address this issue with their tablets. The hospital set up physical depots with staff to dispense, service and repair the devices. It also installed special technology to track the location of the tablets. Everything, from the iPads themselves to the network they use, is fully encrypted, said Geiger. “Patient privacy is very important to us. We don’t want things being mishandled.”

However, from big hospitals to smaller clinics, standards of practice vary. The use of mobile devices and medical apps has yet to be fully standardized and regulated across Canada and many are concerned that the hand-held tablets are too unsanitary for health care. At The Ottawa Hospital, the infection control staff examined the devices thoroughly before distribution to ensure they were not a breeding ground for bacteria; doctors also use antibacterial cleaning cloths to wipe down the tablets after use. Yet at the walk-in clinic in Ajax, Ont., Sutch observed the tablets being passed around to different employees, from nurses to reception staff, and did not see them wipe down the devices once. “I was quite concerned,” she said.

Sutch even spoke to a nurse at the clinic who was also worried about the devices’ potential for spreading germs, especially with the  start of flu season upon us. In 2010, Alberta Health Services created guidelines for cleaning and disinfecting information technology, but it is unclear whether other provinces have followed its lead.

start of flu season upon us. In 2010, Alberta Health Services created guidelines for cleaning and disinfecting information technology, but it is unclear whether other provinces have followed its lead.

Despite her anxieties, Sutch feels that the tablets made for more productive and efficient use of time at the clinic. The nurse was able to access her medical records right in the room. “I think the fact that she had it all right there was perfect.” In a 2011 University of Chicago survey, 75 per cent of medical residents reported that tablet devices allowed them to complete tasks more quickly, and 78 per cent felt that they made them more productive.

Still, such efficiency comes at a steep price. The Ottawa Hospital budgeted $1.2 million for the tablets in 2011 and, on top of the $600 price tag for each device, there are the additional costs of replacing lost, broken or outdated iPads. There are also tentative plans to equip nurses and other staff with mobile devices in the future.

The hospital has recently come under scrutiny as it tries to cut $23 million from its $1.03-billion budget, due to provincial funding cutbacks. In 2012, 16 beds were closed and more than a dozen nursing jobs are being scrapped at the hospital, with more cuts likely on the way. Geiger believes the new technology is worth the added expense, stating that the cost of the tablets will be partly offset by reduced spending on desktop computers and lower training costs.

“We continue to invest regularly in this technology because it’s what we believe is the future of health care,” said Geiger.

According to Dr. Parush, the objective now is to weigh the pros and cons and continue studying and improving upon the existing technology.

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released draft guidelines to regulate medical apps for mobile devices. The guidelines define what is to be considered a medical app and state that mobile devices using attachments, display screens or sensors as a medical device will be subject to the same classifications of the device it simulates. Health Canada is expected to follow suit in the near future. Although he believes in the potential of mobile health to change the medical industry, Geiger admits that, at the end of the day, it does have its limitations.

“We’re not making any outlandish claims about what it does,” said Geiger. “I don’t want to give the false impression you can do everything from an iPad. You can’t. But you can do a lot.”

TOP PHOTO: CHRISSIE DECURTIS