Not Sharing The Burden

OLM managing editor Dan Donovan visited a refugee camp close to the Syrian border in June of this year to prepare a story on the war and the refugees.

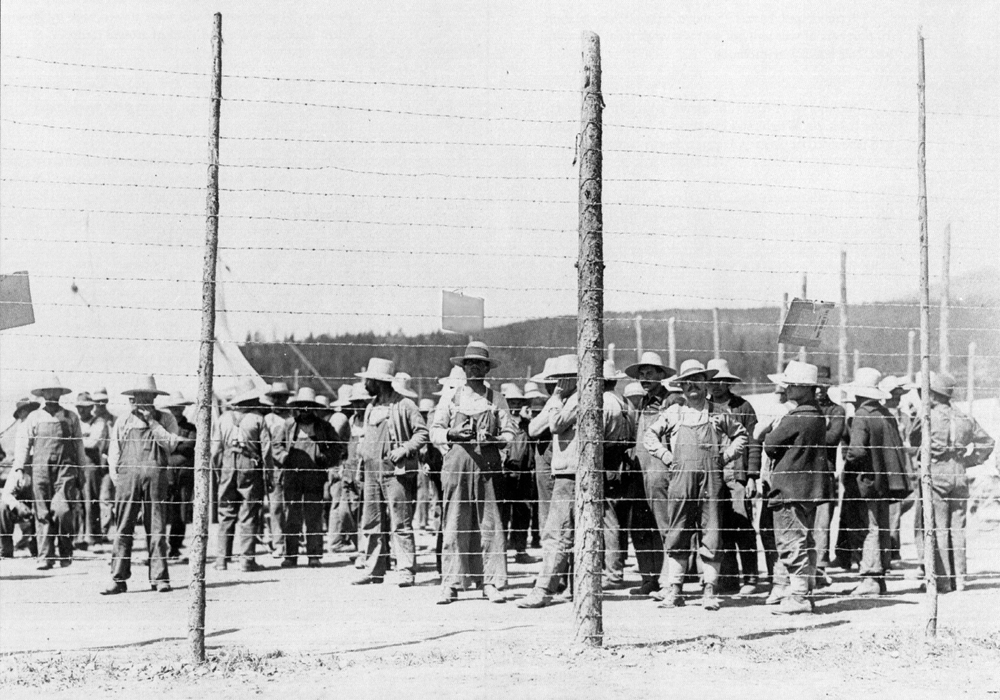

Photos by Dan Donovan

J.R.R. Tolkien once said: “Good stories deserve a little embellishment.”

Nothing could be truer than applying this quote to the Trudeau government and its policy on refugees and immigrants fleeing Syria.

Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper kept Canada’s borders mostly closed to Syrian refugees from 2011 to 2015, citing security concerns.

Then, on Sept. 2, 2015 in the midst of the 2015 Canadian federal election, the body of three-year old Syrian Alan Kurdi washed up on a beach in Turkey.

He died with his five-year-old brother, Galip, and mother, Rehan. Their father, Abdullah, survived.

The family was making a final, desperate attempt to flee to relatives in Canada even though their asylum application had been rejected.

Photographs of his body were taken by Turkish journalist Nilüfer Demir and quickly spread around the world, prompting international outrage. Because Kurdi’s family was reportedly trying to reach Canada, his death and the wider refugee crisis became the issue in the election.

Prime Minister Harper doubled down on the security issue while Liberal leader Justin Trudeau made an immediate pledge to take in 25,000 Syrian refugees in 2015, and thousands more afterwards.

Canadians spoke with their ballots and Trudeau won the election and 25,000 Syrian refugees were allowed into Canada by the end of March 2016.

A short delay, but acceptable given the circumstances.

Since then, the Syrian refugee crisis has remained Canada’s largest resettlement effort since the1970s, with more than 46,700 refugees arriving in 2016.

In January, when newly elected President Donald Trump announced a global travel ban aimed at Muslims from several countries, Trudeau responded to the American decision with a tweet saying “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada.”

This was re-tweeted more than 370,000 times and “Welcome to Canada” began trending in the country.

Trudeau’s comments were echoed by many other politicians including the Conservative mayor of Toronto, John Tory, who told CBS news that “We understand that as Canadians we are almost all immigrants, and that no one should be excluded on the basis of their ethnicity or nationality.”

Trudeau and his cabinet minister’s took every opportunity to talk about Canada’s “diversity and acceptance of refugees.”

At the end of the parliamentary session on June 27, 2017, Trudeau commented again on Canada’s immigration policy telling reporters that “Canadians have been very clear that we see immigration as a net positive, that we know we don’t have to compromise security to build stronger, more resilient communities,” and that, “I will continue to stand for Canadian values and Canadian success in our immigration system as I always have, whether it’s in Washington or in Hamburg next week or elsewhere around the world.”

While Canada’s efforts are laudable, keeping a sense of perspective regarding the numbers is important. Canada is at the bottom end of the list of the Top 20 countries who are taking in Syrian refugees — still a drop in the bucket when compared to the scope and size of the refugee crisis, which is the worst humanitarian exodus since the end of World War II.

World Vision reports that there are 13.5 million people in Syria in need of humanitarian assistance.

Five-million Syrians are refugees, and 6.3 million are displaced within Syria; half of those affected are children.

These children are at risk of becoming ill, malnourished, abused or exploited.

Most Syrian refugees remain in the Middle East: in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt; slightly more than 10 per cent of the refugees have fled to Europe.

However, Canada remains a relatively small player in this global refugee crisis. Canada could do much more to assist in the crisis by using its influence with the European Union and pressure it to meet obligations in this global crisis.

The EU is proving to be an embarras-sing global laggard.

The irony is that the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was created in 1950, during the aftermath of the WWII, to help millions of Europeans who had fled or lost their homes. This program, along with the Marshall Plan saved post-war Europe from starvation and economic disaster.

The United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention, ratified by 145 state parties including EU members clearly defines the term ’refugee’ and outlines the rights of the displaced, as well as the legal obligations of states to protect them.

The core principle is non-refoulement, which asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country when facing serious threats to their life or freedom.

This is now considered a rule of customary international law.

The UNHCR serves as the ’guardian’ of the 1951 Convention and its 1967 protocol.

According to the legislation, states are expected to cooperate with the UNHCR to ensure the rights of refugees are respected and protected. The EU is not complying.

At a time when a record number of Syrians are displaced from their homes and when the United States is turning its back on refugees, EU leadership and money is sorely missing.

Simply put, the EU and its member states are obligated under the 1951 Refugee Convention and the Geneva Convention to provide humane solutions and safe pathways to protection for refugees — and they are in breach of the convention.

Turkey is the only country in the Council of Europe upholding its obligations and is currently hosting more than three-million Syrian refugees. (Turkey has a population of 79 million).

This has put an incredible strain on Turkey.

At first the EU was being overly critical of the Turks for the migrant refugee crisis.

“We’re surprised that the Europeans were saying we should open the borders to Syrians. Our borders have been open for five years,” said Ali Murat Basceri, Minister Plenipotentiary and Deputy Director General for North Eastern Mediterranean Affair. “We all must share this burden. This is massive humanitarian crisis that we have not seen since the end of WWII.”

The EU was forced to act in 2016 when hundreds of thousands of Syrian migrants started heading for Europe via Turkey — then across the Mediterranean to Greece and onwards.

Thousands have died in the Mediterranean crossing in unsafe boats. That crisis led to the signing of a controversial year-old deal between the EU and Turkey which helped stem an unprecedented migration crisis.

It might collapse because of a continuing and increasingly bitter diplomatic dispute between Ankara and the European governments over the EU’s failure to meet its financial obligations under the agreement.

Turkish officials rightly complain that the agreement has not delivered promised financial aid fast enough and has failed to significantly reduce the number of Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

In June, I visited Turkey and at various meetings with officials in Ankara, Istanbul and Gaziantep, I could sense the bitterness and disappointment they felt towards the EU. Paradoxically, the Turks remained hopeful that the EU will change its ways and meet their responsibilities.

Doctors Without Borders has accused the EU of peddling alternative facts, and of falsely claiming that the arrangement with Turkey is a success, a view the agency strongly disputes.

What EU officials fail to mention is the devastating human consequences of this strategy on the lives and health of the thousands of refugees.

Incredulously, the EU is pressing Ankara to seal Turkey’s borders to Europe, while at the same time opening its borders with Syria.

The hypocrisy is startling.

The EU has promised 3.3-billion Euros to help Turkey settle Syrian refugees within Turkey.

However they have only paid 650-million Euros.

Turkish officials say that their immigration and refugees levels are at capacity, and have accused the EU of hypocrisy and self-interest.

Turkey’s reality is that the predominant-ly Muslim secularist and democratic country has chosen to open its borders and assist refugees from Syria.

This at a time when Turkey is part of the NATO coalition fighting Syrian forces inside Syria; fighting a war on its borders with Syria against ISIS, and fighting an insurgency war against PKK terrorists.

To further complicate matters, the Turkish government put down a violent coup d’état attempt in July.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused the Fethullah Gülen and his followers of staging the coup.

Gülen is a Muslim cleric living in the United States under U.S. protection.

He has denied the accusation that he orchestrated the attempted overthrow of the Turkish govern-ment where more than 300 people were killed, 2,100 were injured and several government buildings, including the Turkish parliament and the presidential palace, were bombed by rogue Turkish air force pilots.

After the coup attempt, tens of thousands of people with links to Gülen were arrested while others were dismissed from their jobs.

Many journalists and dissidents including senior judges and prosecu-tors were held without charges.

They are now on trial or awaiting trial.

When asked by Ottawa Life Magazine about the condition and the release of the more than 170 journalists currently being held, Mehet Akarca, Director General of Press and Information in the Office of the Prime Minister said that: “People who are detained are treated well. Many have been released and others involved in the coup are now on trail. It is true that some journalists were detained, but many were people claiming to be journalists, who are not journalists — they are terrorists who are disguising themselves as journalists. So, the courts will sort this out. Turkey is a democracy and there is a process that we are following. This coup was violent and dangerous and we will do what it required to protect Turkey’s institutions. The majority of people arrested have already been released.”

After the coup, President Erdogan called for a referendum to change the constitution to give the president’s office more power — arguing that Turkey required a presidential system (rather than a parliamentary one) to respond quickly to threats at home and abroad.

Opponents of the constitutional amendment said that it was a power grab by Erdogan.

The referendum was held in April and the outcome has left Turkey sharply divided.

A little more than 51 per cent of Turks voted in favour of the executive presidency.

The results fell largely along rural/urban fault lines — the Anatolian heartland voted overwhelmingly for Erdogan’s proposed changes, while the three largest cities (Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir) all voted against. Afterwards, Erdogan said he wants the Turkish people to continue with their noble deeds in helping the Syrian refugees and set a good example to the world.

He noted the solidarity of all the Turkish people in accepting their Syrian neighbours following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011 and said “I thank you. You have a good heart for helping the refugees.”

The Turkish government has since turned its attention back on the EU and the agreement it made in 2016 to assist the refugee crisis by providing Turkey with six-billion Euros.

Looming behind the EU inaction are statistics that show 2016 was the deadliest year on record for Mediterranean Sea crossings by refugees that ended in tragedy, with more than 5,000 deaths.

The Mediterranean continues to be the world’s deadliest route for migrants and asylum-seekers, with 522 people recorded dead or missing so far in 2017.

This figure points to the EU’s deeply flawed approach to asylum and its choice of closing borders over provid-ing safe and legal routes to protection.

Despite its many challenges, Turkey continues to be very generous and has contributed more than $25 billion US to shelter three-million Syrian refugees.

The international community has contributed just over a $500 million US to the effort.

Senior Turkish officials in Ankara, Istanbul and Gaziantep told me that the Turks feel abandoned by the West and the EU, and strongly feel they should not be shouldering the burden of the refugee crisis alone. Officials are very polite but you can feel the displeasure they have towards the EU when they start talking numbers.

“This is the worst humanitarian and refugee crisis in Europe and one of the worst in the world since WWII,” said Ece Ozbayoglu Acarsoy, Deputy Director General for Immigration, Asylum and Visa at the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“Turkey should not be doing this alone and we continue to press the EU and others to assist.”

The numbers don’t lie.

Since 2012, the brutal war in Syria has killed 470,000 people and left seven million displaced.

The reality is that 10 countries which account for just 2.5 per cent of the global economy, are hosting more than half the world’s refugees. Wealthy countries have left poorer nations to bear the brunt of a worsening crisis.

Despite the magnitude of the tragedy and the inability or even refusual of most EU nations to assist the refugees, the guiding principle of the Turkish government for Syrian refugees is it’s an open door.

Today, one in every 24 people in Turkey is a Syrian refugee.

Turkey has provided a new type of shelter to the refugees who now live in container-type homes (rather than tents) with solar powered electricity and water.

The Turkey Prime Ministry Disaster and Emergency Management Authority manage the refugees who live in and outside the centres. The Authority provides more than 250,000 refugees with health, education, social services, and shelter while each family also receives the equivalent of $250 monthly.

The centres also provide schooling for 508,846 Syrian students and vocational training for 222,869 Syrian adults.

Gaziantep

The general manager of the Nizip-2 Syrian refugee camp greets me at the entrance to the camp.

He has a gentle demeanour and friendly laugh.

The camp is a short distance from the city of Gaziantep, a short distance to the Syrian border.

It’s a hot day in the middle of Ramadan.

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar.

It begins on the last full moon of the month and lasts 29 or 30 days, depending on the year.

The holiday of Eid al-Fitr marks the end of Ramadan and the beginning of the next lunar month.

Ramadan celebrates the date in 610 A.D. when, according to Islamic tradition, the Quran was first revealed to the Prophet Mohammed. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims are called upon to renew their spiritual commitment through daily fasting, prayer and acts of charity.

It is a time to purify the soul, refocus attention on God and practice self-discipline and self-sacrifice.

Fasting during the month of Ramadan is considered one of the five pillars of Islam that shape a Muslim’s life.

The physical fast takes place on a daily basis from sunrise to sunset. Before dawn, those observing Ramadan will gather for a pre-fast meal called the suhoor; at dusk, the fast will be broken with a meal called the iftar.

Both meals may be communal, but the iftar is an especially social affair when extended families gather to eat and mosques welcome the needy with food.

For this reason, as I walk through the camp most people are either in the container homes resting or at work.

I notice there are many children outside playing.

They stare and smile at me as I walk around. Several wanted to see how my camera worked.

There are elementary and high schools in the camp and I am escorted into one of the elementary school classrooms.

The rooms are air-conditioned and bright and there are lots of colouring books and crayons and drawings. The walls are decorated with their artwork.

The children are so innocent. I think back to when my kids were in elementary school in Ottawa. This could be their classroom.

Inside it looks very much the same.

The female teachers are all smiling and ask the children to say hello to me.

It’s so sad and heartbreaking and wonderful all at the same time.

I feel like crying for the tragedy of it all, but don’t succumb.

The manager tells me that it is critical to ensure that the children have some kind of normalcy and education so the war does not leave a lost generation of children without knowledge.

He says many of the children are traumatized when they first arrive but once they adjust and have some normalcy they do better.

The Turks are doing such amazing things here.

We head back to the camp office and have some tea.

The camp manager says he was happy when he heard that Canada helped the refugees.

“I know it’s not a lot of people you took, but it is important and it is appreciated. Canada is a good country – thank you for helping.”

He then says, “Your guy he does yoga. He is the good looking guy with the socks. How is he?” We all laugh. “Prime Minister yoga with the socks”, I say. “He’s fine. A good guy.”

An odd moment, but a nice one. Go Canada.

The town of Gaziantep is just a short distance from the Syrian border. It’s a quiet and scenic place that is now home to 336,410 Syrian refugees who found a safe haven here.

The bombings, the chemical weapon attacks and the violence of their homeland give way to the peaceful existence to be found in the shops, courtyards, cafes and restaurants of this city of 1,889,466 people.

For many Syrians, Gaziantep is the final destination – the place where they will wait out the war.

The mayor of Gaziantep is tour-de-force named Ms. Fatma Sahin, a passionate, no-nonsense, strong-willed and charismatic leader. The 40-ish year-old Sahin’s compassion, authenticity and commitment to helping her Syrian neighbours is palpable.

“There is an understanding here about what is happening to the Syrian people. They are running away from a war, they are running away from violence, from destruction, from bombs, they have lost their homes, some have lost family and it is very sad . . . they are afraid and we are their neighbours. We must help. We are helping we are doing our best. The Syrians are good people — they aren’t trying to make problems here,” she said.

The fact that Gaziantep’s population has grown by almost 350,000 in only a few years does not weigh down on her or her staff.

She says that city residents have been very responsive to the refugees, and want to help.

The system and services that Gaziantep is providing with help from the Turkish government is incredible.

Sahin says the Syrian migration flux is not a short-term and temporary situation, but a permanent case.

Her primary focus is to use a holistic approach to deal with the refugee issue and provide efficient social services in education, health, economy and security.

The approach includes budgets for emergency response, humanitarian aid capacity building, social development and need-based programs to aaccelerate social cohesion and social acceptance.

The city also provides close coopera-tion with international institutions, universities and NGOs.

Education and jobs are top of mind for Sahin who said — “We absolutely need to ensure that the children who are refugees have full access to education so we do not find ourselves several years from now with a lost generation of young people who have no education.”

So far, Syrian students are enrolled in 54 schools in Gaziantep and it has become mandatory for each school to increase the number of classrooms to support the Syrian students.

There are also two information and training centres used as temporary education centres for students who have lost their families and/or have financial problems.

All student expenses including transportation are covered by the municipality.

To increase prosperity, harmony and acceptance the city has also developed job-training programs and provided employment opportunities to Syrians and established a common market and free trade zones for Syrian businessmen to connect with their network abroad.

The Gaziantep city policy is to encourage Syrians to work.

Registered Syrian refugees benefit from health services free of charge all over Turkey.

To address the high demand for shelter, the Gaziantep Metropolitan Municipality is constructing 50,000 new homes.

Sahin says that the problem is huge but can be addressed and alleviated.

“We were able to create successful examples in Gaziantep and we can multiply these successful examples but we need support to achieve this.”

Her hope is that the EU and others will meet their obligations and assist the refugees with monetary, and other, supports.

She adds that in the next few years: “We must increase the number of children attending school from 60,000 to 100,000. We aim to support the children financially till they complete college or vocational education and are able to support themselves.”

Mayor Sahin adds that building new schools and hospitals are great needs in Gaziantep that require resources and she is committed to getting them built.

We talk briefly about the EU and their non-payment. She sighs, agrees it is not helpful and says Turkey has to continue to work on what it is doing for the refugees and hope that Europe will eventually do its part.

I see the disappointment in her eyes when we address the issue, but she is not one to be constrained by what is not happening.

She is focused very much on what she can do and what can be done.

I don’t think I have ever met such an impressive politician and mayor.

The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal Explained

Greece has begun its forced deportations of migrants to Turkey.

The EU says the deal will prevent deaths, critics say it compounds misery.

WHAT IS THE DEAL?

Anyone arriving illegally in Greece after March 20, 2016 is sent back to Turkey if his/her asylum application is rejected.

The EU has said people found to be “requiring international protection” will be accepted if an application is made for asylum through the official channels.

In exchange for every person returned, the EU will resettle one Syrian refugee stuck in camps across Turkey. Priority will be given to those who have not previously tried to enter the EU illegally.

The EU has said the deal is aimed at slowing the uncontrolled, dangerous and deadly journeys people have been undergoing to reach the European mainland.

A statement from the EU called the deal “a temporary and extraordinary measure which is necessary to end the human suffering and restore public order.”

WHAT DOES TURKEY GET?

In exchange for accepting those who are returned, Turkish nationals can gain access to the EU’s passport-free Schengen Zone, allowing for visa-free travel around European countries that are part of the zone. This was to begin this year but is stalled.

The EU has also pledged 6.8-billion Euros in aid to Turkey to help with the refugee crisis. This includes working with Turkey along the border with Syria to “improve humanitarian conditions.”

The EU has only paid $740-million US of the 8-billion owed to Turkey, and this process also appears stalled.

The EU and Turkey agreed to increasing talks about Turkey’s bid to join the EU, with discussions beginning this summer. These discussions stalled because of European intransigence.

WHAT DOES THE EU GET?

Under the agreement, Turkey is obliged to “take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU.”

Turkey did this and it has helped temporarily ease the refugee burden on Greece,

In order to qualify for EU membership, the deal obliges Turkey to “take the necessary steps to fulfil the remaining requirements” for membership. This is thought to be a reference to Turkey’s questionable human rights record.

WHAT HAPPENS TO THE PEOPLE CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE?

Anyone arriving in Greece illegally or who has an asylum application rejected is sent back to Turkey.

The EU has said people will still have applications processed individually. According to the UN, thousands of people are now being held in a state of limbo on the Greek islands as they await their fate. The agency said conditions are becoming increasingly poor as people are not being allowed to continue their journeys.

WHEN DID IT START?

The deal came into effect on March 20, 2016, meaning any Syrian refugee arriving in Greece after this date would fall under the ‘one-in-one-out’ agreement.

WHO DOES IT AFFECT?

The resettlement part of the deal only applies to Syrian refugees because Afghans, Pakistanis and other nationalities are not deemed entitled to European protection.

These nationalities could be sent back to Turkey under a different part of the agreement, but this will not lead to anyone being resettled in Europe.

HOW HAVE PEOPLE REACTED TO IT?

There has been anger, protests and violence in both Greece and Turkey over the deal.

On Chios, a Greek island where many asylum seekers land, clashes around a registration prompted migrants and refugees to walk out and a medical charity extracted its staff because of the risk.

Refugees on Lesbos said they would jump in the sea if they were sent back to Turkey.

In the Turkish port of Dikili, where many of the boats will arrive, there were demonstrations against the setting up of a refugee camp. Three days before the returns were due to begin, hundreds fled from the Greek camp in which they were being held, while others tried to sail from Greece to Italy.

WHY ARE HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS AGAINST THE DEAL?

Rights’ groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have criticised the deal as breaking EU law, and also being a breach of the UN refugee convention. The convention bans mass expulsions of any people under any circumstances; something rights’ groups argue is going to be the upshot of this agreement.

The EU argues that it will be assessing claims individually, but the recent classification of Turkey as a safe country for refugees — a status that is being used to justify the return deal -it is likely many people will be sent there en-masse.

WHAT IS A SAFE THIRD COUNTRY, AND IS TURKEY ONE?

If a country is not going to keep an asylum seeker in situ while the application is being processed, he/she needs to be sent somewhere that is safe while the paper work is being assessed.

This means that their lives and well-being cannot be in danger in the country they are sent to by the country processing their application.

Turkey has not previously been designated a safe Third Country, in part because it is not a full signatory of the UN refugee convention.

Turkey has granted temporary protections to Syrian nationals, including temporary work visas and access to health care and education