by Chris R. Kilford

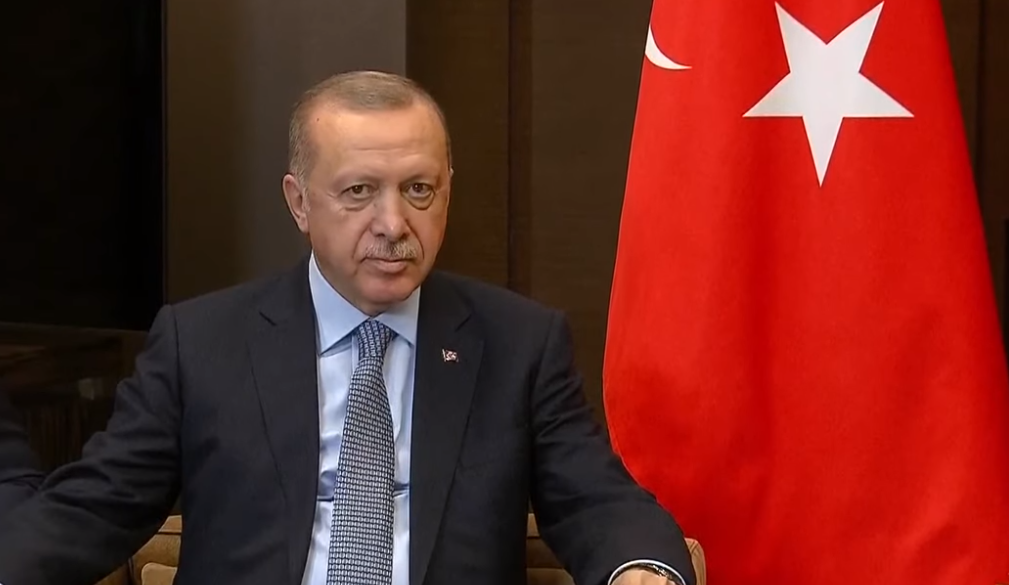

International eyes will soon turn to the 2023 Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections and whether President Erdoğan (pictured above) and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) will continue in power.

Relations between Canada and Turkey have generally been good since the two countries established diplomatic ties in the 1940s. But stumbling blocks do exist, including the Canadian government’s recognition of the Armenian genocide in 2004. As the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs webpage regarding Turkey-Canada relations currently notes, “the Canadian government’s position and the resolutions adopted by both Chambers of the Canadian Parliament regarding the events of 1915 do not comply with historical facts and create difficulties in Turkish-Canadian relations.” That said, since 2004, many other governments have also passed resolutions recognizing the Armenian genocide, somewhat diluting Ankara’s pointed frustration with Ottawa. Certainly, the volume of bilateral trade between the two countries has increased year over year, from just under $1 billion in 2004, to $3.6 billion in 2019. In June 2019, Canada and Turkey also signed a Joint Economic and Trade Committee agreement designed to further expand trade and investment.

While growing bi-lateral trade is a good sign that relations are on track, friction has occurred over Canada’s recent granting of political asylum to Turkish citizens. Prior to 2016, it was rare for Turks to claim refugee status in Canada, although some did after the 2013 Gezi Park protests that swept through Turkey. But following a July 2016 failed military coup attempt, which the Turkish government blamed on followers of Turkish Islamic cleric Fetullah Gülen, matters changed dramatically. Between 2017-2019, for example, 4,697 Turkish citizens were granted refugee status by Canada, the highest number of accepted claims from any country. And while not every Turkish refugee accepted by Canada was a member of the Gülen movement, the assumption by the Canadian government was that most were and would be at risk if they returned to Turkey.

Confirmation on the risk that followers of Fetullah Gülen might face if they returned to Turkey was made clear during a speech by the Turkish Ambassador to Canada in Ottawa, on the third anniversary of the July 2016 coup attempt. The Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETÖ), as Turkey now calls the Gülen movement, had perpetrated one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in Turkish history, said the Ambassador, using fighter jets, tanks and helicopters in an attempt to overthrow the Government. Indeed, he continued, FETÖ was “a highly secretive and criminal religious cult” with a “dark underbelly” that was “involved in numerous covert activities such as targeted killings, evidence fabrication, wiretapping, disinformation, blackmail and judicial manipulation as well as money laundering.” The evidence that FETÖ was behind the coup attempt, he added, was conclusive.

In his speech, the Ambassador was also clear that the Gülen movement was active in Canada and employing deceptive tactics “to show themselves as charity or non-profit organizations and manipulate the Canadian system of tolerance and multiculturalism.” A particular point was also made about the January 2018 decision by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada to add Turkey to a narrow list of expedited countries for asylum approval that included, for example, Afghanistan and Eritrea. Canada is not the only Western country to offer asylum to Gülen members, and in his final remarks, the Ambassador noted that Turkey was determined “to fully eliminate all structures of FETÖ in Turkey and beyond.” Clearly, this was a warning directed at Gülen members seeking shelter in Canada.

The latest cause of friction between Canada and Turkey occurred in October 2019, when Turkey launched Operation Peace Spring in northeastern Syria. This cross-border military incursion was focused on pushing back the Kurdish dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and creating a safe zone along the Turkish-Syrian border, where some of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees Turkey is hosting could be resettled. For the Turkish government, the SDF is simply a cover for the Syrian-Kurdish YPG, which it considers part and parcel with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). It has been fighting the PKK inside Turkey for decades and up until 1998, the PKK found safe haven in Syria.

As a result of Operation Peace Spring, Canada and several other Western countries placed arms embargoes on Turkey. This was a significant move, because when it comes to Canada’s international arms trade, Turkey ranked in fourth place behind the United States, Saudi Arabia and Belgium in 2018 with sales to Ankara of almost $116 million. Now, any new permit requests to export military items to Turkey, said the Canadian government, would be “presumptively denied.” On the other hand, the notice to exporters did add that if exceptional circumstances warranted, especially in relation to NATO cooperation programs, a permit could be issued, and permits issued prior to October 11, 2019 would remain valid. However, the decision on April 16, 2020 by the Canadian government to extend the ban on arms sales to Turkey until further notice was not well received in Ankara.

From the Canadian government’s perspective, the arms embargo was justifiable on the grounds that Turkish military operations in Syria were directed at the SDF, who had previously been instrumental in defeating the so-called Islamic State. From the Turkish perspective, however, the main objective was to neutralize what it considers to be the PKK, which Canada also recognizes as a terrorist organization. And Ankara’s perspective should not have come as a complete surprise as Canada’s own travel advisory website for Turkey recognizes that the PKK continue to launch “deadly terrorist attacks against Turkish security personnel in several cities and regions in the south and southeast of the country.”

When it comes to arms embargoes, it is also curious that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) aren’t similarly sanctioned by Canada. The Saudi government has blockaded Qatar since June 2017, alleging that Doha supports terrorism, is heavily invested in the Yemeni-civil war and supports General Haftar’s anti-government forces in Libya. The same is also true of the UAE, also a “top-ten destination” for Canadian military goods and technology in 2018. Ironically, it is NATO-member Turkey that is supporting, politically and militarily, the United Nations-backed government in Libya against General Haftar’s forces.

Given these three friction points, what about the future of Canada-Turkey relations? On the surface, both countries are members of the G20 and NATO, and in 2018, 109,189 Canadians visited Turkey. Bi-lateral trade has also steadily increased, boosted by organizations such as the Canadian-Turkish Business Council, formed in 2001, and its Turkish counterpart. High-level political visits by both countries have also continued, including a visit by Canada’s Speaker of the Senate to Turkey in May 2019. Beneath the surface, however, there is recognition that Turkey’s domestic political situation is very delicate. Canadians, for example, are warned on the government’s travel advisory website for Turkey that “Turkish authorities have detained and prosecuted large numbers of people over social media posts” and “to think twice before posting or reacting to online content criticizing the government.”

COVID-19 has also exposed widespread economic weaknesses in Turkey. As the World Bank noted in its April 2020 update, Turkey’s overall macroeconomic picture was already “uncertain, given rising inflation and unemployment, contracting investment, elevated corporate and financial sector vulnerabilities, and patchy implementation of corrective policy actions and reforms.” On the other hand, Turkey’s recovery after its own 2001 economic collapse and the 2008 global financial crisis points to a certain resiliency. Nevertheless, Canadian and other foreign investors are wary and this is unlikely to change in the near future. Indeed, international eyes will soon turn to the 2023 Turkish presidential and parliamentary elections and whether President Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) will continue in power. However, regardless of who is in power, restoring international and domestic confidence in Turkey’s overall economy and its tourism industry will need to be a policy priority, along with increasing market access in what will hopefully be a more stable domestic and regional environment.

Dr. Chris Kilford is a Fellow with the Queen’s Centre for International and Defence Policy. He is also a former defence attaché to Turkey, serving there from 2011-2014.

This article was first published on May 29, 2020 by The Canadian International Council (CIC). The CIC is a platform for citizens to engage in discussions on international issues. Their mission as an independent, non-partisan and charitable membership organization is to involve Canadians in defining Canada’s place in the world.

Photo: via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHZHoBNs_Hg