In November of 1936, in the depths of the Great Depression, incumbent Democrat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was running for re-election in what appeared to be an extremely hostile political climate. The American unemployment rate was roughly 25% and there was an ideological divide in much of the country regarding the reception of Roosevelt’s New Deal plan to boost employment, not to mention the then-unprecedented expansion of the Federal government required for its implementation. According to the Literary Digest, the nation’s most respected polling source at the time, the Republican Governor of Kansas, Alf Landon, was well on the way to defeating Roosevelt with a commanding margin. But, when election night drew to a close on November 3, 1936, the polls would tell a different story.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt not only defeated Landon, but he did so by the largest Electoral College margin in American history. Roosevelt obtained a staggering 523 Electoral College votes, representing over 60% of the popular vote and 46 of the then 48 states. Landon, on the other hand, was only able to gather a miniscule 8 Electoral College votes and roughly 36% of the popular vote as well as just 2 states. The Literary Digest’s dead wrong polling prediction resulted from an unrepresentative and skewed sample which was concentrated in the state of Maine alone and which relied upon responses from fewer than one quarter of the anticipated respondents in that state. Furthermore, due to the Literary Digest’s predominantly white-collar readership base, the majority of those who did participate in the already under-represented survey were more likely to support Republican Governor Landon than the incumbent Democrat President who advocated a less business friendly and more regulatory laden approach to governance, thereby skewing the poll’s sample even further. Not surprisingly, in the wake of the unanticipated election results, the Literary Digest’s polling operations lost all credibility, and the magazine ceased publishing shortly thereafter.

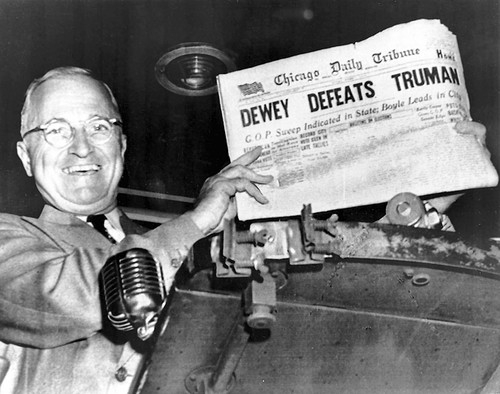

History would repeat itself twelve years later when, in the general election of 1948, another American polling miscalculation again predicted a victory for a candidate who would never move into the White House. In 1948, Democrat President Harry Truman — who had served as Vice-President in Roosevelt’s fourth term and who was sworn in as President after Roosevelt’s death in the spring of 1945 — ran his first campaign for the presidency against the moderate Republican New York Governor Thomas Dewey and the more radical States’ Rights or “Dixiecrat” Party candidate Strom Thurmond. At the time, renowned pollster Elmo Roper, like the majority of the other pollsters in America, was predicting a large win for Thomas Dewey. In fact, the Chicago Daily Tribune was so confident that Truman would be defeated that, on the evening of the election, it set the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” on the front page of the morning edition for the following day without waiting to confirm the election results.

The results were not quite what the Chicago Daily Tribune, and much of America for that matter, expected. Not only did the incumbent President Truman defeat his Republican challenger, but the Democrats also picked up a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Once again, the pollsters were dead wrong and, as was the case in 1936, this discrepancy could be traced back to an unrepresentative sample. The majority of the pollsters stopped canvassing and sampling respondents in the pivotal final few weeks before the early November election. Elmo Roper’s polling ceased almost two full months before election day based on the assumption that voters’ opinions wouldn’t change in the period between the end of the primary contests and the general election itself. Thus, the belief in the inflexibility of voters’ opinions, which resulted in a lack of up-to-date polling, led to a polling blind spot: the increasing favorability of Truman and the Democrats that was building in the final few days of the election campaign went almost completely unnoticed.

Sixty-four years later, the recent unexpected defeat of Alberta Wildrose leader Danielle Smith by incumbent Progressive Conservative (PC) Premier Alison Redford in the Alberta provincial election demonstrates that the same reasoning which led to the unanticipated election victories in 1936 and 1948 is alive and well inCanada. The vast majority of Canadian political pundits, pollsters and commentators were predicting that an easily-won Wildrose majority government would form the next provincial government with Danielle Smith as the first non-Progressive Conservative Premier in 12 election cycles — or more than 40 years. They had it wrong, most likely because of a flawed sample.

In the weeks preceding the election, virtually all the polls across the province of Alberta reflected the likely scenario that Danielle Smith and her recently formed, more conservative Wildrose Party would be swept into power. These polls were neither inaccurate nor misleading. However, what the majority of these polls missed was the change in voter opinion which took place in the last three days before Albertans voted. Many of the polls relied on by political pundits, pollsters and commentators as barometers for the public opinion of Albertans consisted of out-of-date sampling research and responses. In other words, since most pollsters in the province stopped contacting respondents to gather information prior the critical 72 hours before the election itself, the polls were inaccurate due to a sampling method that was beyond its “best before” date and which was therefore unrepresentative of the voters’ true perceptions. At least three days out-of-date is better than the nearly two months out of date which characterized the polling of Elmo Roper and that of many others during the 1948 American presidential election.

Today, it is business as usual in Alberta politics. Premier Alison Redford and her Progressive Conservatives (PC) will remain in power with the party’s 12th consecutive majority government, albeit with a smaller majority than has been the case since the year of Canada’s centennial celebration in 1967. But when it comes to conducting the accurate polling of voters’ public opinion, mistakes from yesteryear surface yet again in 2012, shocking the political pundits, pollsters, commentators and the general public. Once again, the more things change, the more they stay the same.