Rail: The Light at the End of the Tunnel

Rail Series: By Claire Tremblay and Harvey Chartrand

Nothing quite defines pioneering Canada as its railways. Think rail and the image of thousands of miles of steel stretching the length of our great country comes to mind. Ottawa Life begins a look at the railway industry with an overview of the history of rail in Canada and, specifically, a look back at a time when Ottawa had a sophisticated downtown rail service and streetcar network.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line completed in 1885 – linking eastern Canada and British Columbia – was an engineering marvel of its time. During the first half of the 20th century, rail was the nation’s spine, along which cities, industry and agriculture were built, grew and continue to thrive to this day. CPR’s logo of the hard-working beaver was a symbol of Canadian industriousness.

Canada would not be the prosperous country it is today without its rail system.

Rail first made its appearance in Canada in 1836 with the opening of the Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad outside Montreal. Four years later came the Albion Railway in Stellarton, N.S. Both rail lines served a commercial purpose. The Montreal rail link connected traffic on the St. Lawrence and Saint-Jean rivers; the Nova Scotia line linked coal mines to a seaport.

However, it wasn’t until the 1880s and the creation of the CPR that rail became prominent in Canada. British Columbia demanded a transport link to connect it to eastern Canada as a condition of joining the Canadian Confederation in 1871. In response, the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald announced the creation of the CPR and construction of a 3,000-mile east-west rail link. Nothing so epic had been built before and it was promptly declared to be an impossible venture by Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. Yet the creation of the CPR had a domino effect. It might have started off being about B.C., but the CPR was really all about forging a nation.

Today, the CPR, formerly also known as CP Rail, is headquartered in Calgary and consists of 14,000 miles of track across Canada and into the United States. The rail network stretches from Montreal to Vancouver and north into Edmonton; it also serves major cities in the US including Minneapolis, Chicago and New York City.

Canadian National Railways (CNR) was created in June 1919, taking over several railways that had gone bankrupt and fallen into federal government hands, along with railways already owned by the government. The railway was referred to as Canadian National Railways (CNR) until 1960, when it was renamed Canadian National/Canadien National (CN). In 1995, the federal government privatized CN.

Today, CN owns about 20,400 miles of track in eight provinces, as well as a 70-mile stretch of track into the Northwest Territories to Hay River on the south shore of Great Slave Lake; it is the northernmost rail line anywhere within the North American Rail Network, as far north as Anchorage, Alaska. Following CN’s purchase of Illinois Central and a number of smaller US railways, it also has extensive trackage in the central US along the Mississippi River Valley from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. CN is headquartered in Montreal.

And while some might think railway’s golden days are over, as road transportation has taken precedence, nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the coming decades may prove to be a platinum era for rail – one even more powerful than the first golden age. Global warming and the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions make rail an attractive alternative mode of transport for passengers and freight. Rail also facilitates cross-border transportation and exports between Canada and the United States. Special technology permits rail freight cars and containers to be quickly X-rayed and waved through U.S. Customs and Border Protection. This compares favorably to the much longer customs-clearing process involved in screening goods hauled by truck into the U.S.

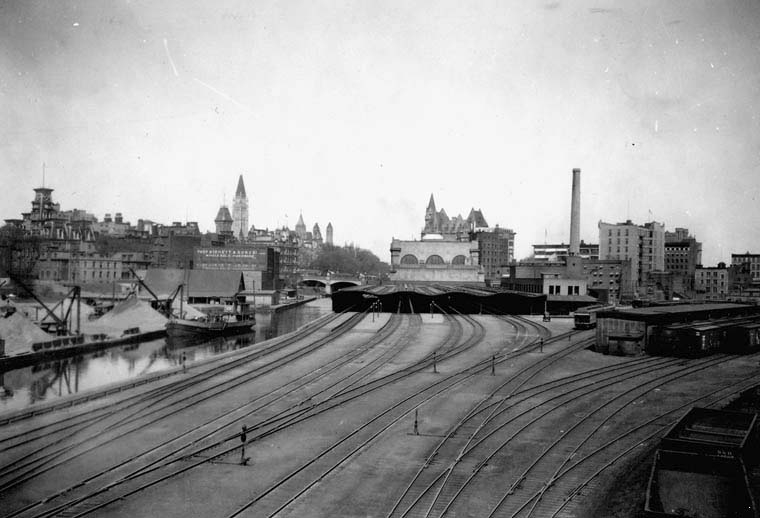

Ottawa used to be a railway town. Downtown was criss-crossed by streetcar tracks and passenger and freight rail lines. The Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade at 125 Sussex Drive (aka the Lester B. Pearson Building) was once the site of a busy rail freight yard. You can still see the supports of the old Bytown and Prescott Railway Bridge (from Stanley Park in New Edinburgh to Bordeleau Park along King Edward Avenue) on which trains once ran in and out of the yards. Did you know that the bicycle path that cuts through Rockcliffe Park was once a streetcar line? The Queensway, the Vanier Parkway, the Ottawa River Parkway, Colonel By Drive (from Echo Drive to Besserer Street) – all were once rights-of-way for rail lines.

At one time, a railway track ran across the center of the Alexandra Interprovincial Bridge, crossing old Hull on a long-vanished trestle that led to a commuter rail line linking Wakefield to downtown Ottawa. Only traces of the line remain in Gatineau today; most of it was ripped up to make way for linear parks and bicycle paths. The CPR right-of-way north of Sappers Bridge was shared with the Hull Electric Railway, which ran on either side of the CPR line. Before 1912, when the Union Station at Confederation Square was built, the station for the railcars was under the Dufferin Bridge. After the Chateau Laurier opened, the tracks north of Dufferin Bridge were enclosed under a terrace and passenger platforms were provided. The Hull Electric had a pair of crossovers to the CPR track, beside the Chateau Laurier. There was also a turning loop, in a tunnel under the new Plaza Bridge built in 1912 to replace the Dufferin and Sappers Bridges.

Lebreton Flats was once the site of Ottawa’s first railway station: the Canada Central Union Station was opened in May 1881 to handle Canada Central Railway and Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway trains. The station was located at Broad Street at the west end of Ottawa Street (vestiges of these now crumbling thoroughfares can still be seen in Lebreton Flats). The architecture of the station and freight sheds is the typical Victorian style with roof-end cross-bracing and carved rooftop finials. The Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway reached Broad Street via the Prince of Wales Bridge on December 3, 1880. This interprovincial rail bridge has somehow survived, although it is now disused and in dire need of an upgrade. Efforts to integrate the old bridge into an interprovincial light rail transit system have failed repeatedly.

The Canadian Pacific roundhouse at Ottawa East was constructed in late 1899. The CPR erected a roundhouse for steam engines at Hurdman’s Bridge across the Rideau River, near the present-day Queensway Bridge. The roundhouse was located between the CPR and the Canadian Atlantic Railway bridges and had four tracks leading into it.

The Ottawa and New York Railway opened a line to Ottawa on July 29, 1898, ending at Hurdman Station. A huge railroad yard occupied land from the south end of the University of Ottawa campus (where Colonel By Hall and the Sports Complex were later built) to the Ottawa Gas Works on Lees Avenue, where a coal gasification plant operated for many years.

In 1911, the CPR’s 21-stall Ottawa West roundhouse was built in Hintonburg (near the present-day Tom Brown Arena). The spectacular roundhouse was demolished in the early sixties when Lebreton Flats (a thriving working class district) was flattened. The CPR’s Ottawa West roundhouse had walls made of reinforced concrete construction, as were the columns and beams. The joists, on the other hand, were of white pine and B.C. fir. The site of the old roundhouse is now covered over by the Transitway near Bayview Station.

One of the least-remembered places in Ottawa is “Little Sussex Street”, which was located right behind Union Station on what is now the Colonel By Drive extension as it approaches Rideau Street. Little Sussex Street catered to rail passengers and employees out for a good time; it was very close to two legendary taverns in the Grand Hotel and the old Albion Hotel.

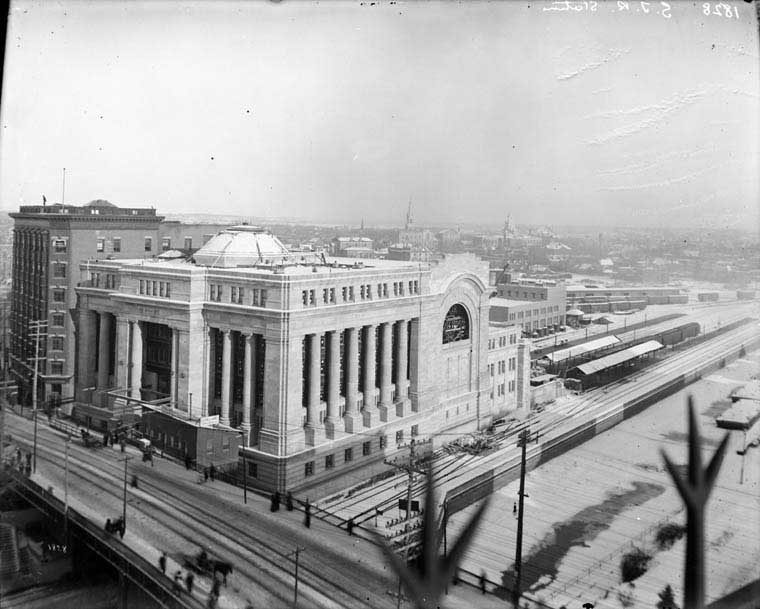

The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) purchased the Canadian Atlantic Railway in 1904. Through its Ottawa Terminals Railway subsidiary, the GTR rebuilt the passenger and freight trackage at the Central Depot in 1908-1909, and began construction of a new station on the site of the Canada Atlantic Central Depot at Rideau Street and the Canal. It was intended as a Union Station, to unify the various railway termini on the model adopted for the recently-built Washington, D.C., Union Station. At this time, few other monumental stations existed in North America.

A classical revival structure was designed by the architect Bradford Lee Gilbert. However, before the station was built, the General Manager of the Grand Trunk, Charles Melville Hays, replaced Gilbert with the architects Ross and MacFarlane. The redesigned station had plain, unfluted columns on the main building, but elaborate arched windows on a Roman model in the waiting room section. A small dome with a cylindrical beacon on top surmounted the main structure.

The largest room in the station was the full-height waiting room, with arched coffered ceiling, eight large semicircular windows, and eight Corinthian columns, reminiscent of the great Roman baths. Around it were washrooms, lunchroom, ticket offices and other facilities. Today the waiting room sits in magnificent decaying isolation, off-limits to the general public.

Behind the waiting room was a three-storey office building, used mainly for railway operations, and the full-width concourse for passenger circulation, with doors leading to all platforms. The concourse also had a newsstand and the side entrance to the taxi stand and car pickup area. Along the east side of the shed was the baggage room, as well as railway express offices with truck loading bays, postal room and steam plant. The baggage room adjoined the south side of the concourse near the Besserer Street ground-level entrance, convenient to the taxi stand. Much of this was bulldozed in the early 1980s to make way for the Rideau Centre mall and the Ottawa Congress Centre.

The train shed had a complex roof covering of concrete slabs, glass skylights, smoke ducts over the tracks, and air vents between the tracks. The concourse also had large skylights in the roof.

When Union Station opened on June 1, 1912, the CPR declined to use it for all but its Montreal direct-line trains and remained at Broad Street. The Canadian Northern Railway also did not use the station, but remained at Hurdman.

As most other railways did not use the station, it was named “Grand Trunk Central Station”. The name appeared in large Roman letters above the Rideau Street entrance and along the top of the wall on the Rideau Canal side. There was also a freight yard to the east, ending at Besserer Street, but it had no connection with the passenger tracks.

A 1911 drawing of the train shed cross-section shows the canal-side track outside the original concrete wall of the train shed. It was labelled “CPR Transcontinental Through Track” and implies that the station really was built by the GTR with the intention or understanding that the CPR transcontinental trains would bypass it.

When in January 1920, CPR decided to close Broad Street Station and move to Union Station, the train shed wall was taken down and moved to the canal edge. The relocated wall of the shed did not rest on the canal wall but was supported on pilings set into the canal itself. The original architects evidently had no intention to lay out Track 1 with sufficient clearance for it to be inside the shed; otherwise, they would have allowed sufficient clearance to add the wall.

On July 31, 1966, Union Station closed and the railway tracks were removed. Under the John B. Parkin Associates Plan for the redevelopment of Confederation Square, the station was to be demolished! However, Union Station was reprieved to become the Centennial Centre, containing exhibitions open to the public during Canada’s centennial year of 1967. The station buildings were then remodelled to become the Government Conference Centre. The concourse was divided into smaller rooms, but the waiting room became the main conference hall.

The Chateau Laurier was built as the Grand Trunk’s station hotel, and opened the same day as the station. There was no ceremony for either opening, as the Grand Trunk’s chairman, Charles Melville Hays, had died in the sinking of the Titanic while travelling to Canada for the opening. The hotel basement was connected by a pedestrian tunnel to the station’s waiting room, emerging between the two flights of the grand staircase from the Rideau Street entrance, and a steam tunnel which connected the hotel to the shared steam plant.

On December 2, 1909, the GTR was authorized to construct a branch line from its track south of Sapper’s/Plaza Bridge thence northerly under the bridge, crossing CPR and the Hull Electric Railway, and into the site of the Chateau Laurier Hotel. This siding was used to bring in materials for the construction of the hotel. On June 28, 1911, a plan was approved showing a terrace or covering over the tracks of the CPR and Hull Electric, immediately adjacent to the Chateau Laurier. The terrace was rebuilt in 1960.

Ottawa’s great railway era seems to have ended when the National Capital Commission accepted the Greber Report recommendations to remove all traces of rail from downtown Ottawa, capitulating to the French urban planner’s whims. Ottawa was a much more atmospheric city back in those days. Much of that ambience had to do with the dynamic and bustling presence of rail. As Ottawa looks at new light rail transit, could we be returning to that golden age? Time will tell.

Sources – Wikipedia; The Railways of Ottawa: Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages