Reinventing the Wheel: How E-bikes Are Revolutionizing Cycling

The crisp March air filled Julie’s lungs as she walked along the sidewalk. One unsure step brought a crack: the sound of her leg snapping as she fell sprawled across the ice. Two years later, she can still only take about 20 steps at a time as she recovers from a long string of surgeries. But in 2012, about a year before her accident, Julie Albers made a purchase that would put her back in the driver’s seat after her injury. She bought an electric bike.

“I like to walk places, but after breaking my leg I can’t go as far anymore. But with my e-bike I can,” she said, speaking fondly of her spunky blue scooter.

Julie isn’t the only e-bike convert out there.

Worldwide e-bike sales reached over $30 million in 2013, according to the 2015 Electric Bikes Worldwide Report. There are more than 200 million on the roads today and global e-bike sales are estimated to reach two billion units by 2050, according to the report. The Canadian market sees about 20,000 e-bike sales per year –about a tenth the size of the US market– and it’s growing as more people make the switch.

E-cycling allows much of the older population, as well as those with mobility issues, to shred the pavement the way they did as children. Recharging the battery costs a fraction of the price of a tank of gas – only a few cents a day.

But recently e-bikes have come under fire in Ottawa from traditional cyclists and policy makers, including officials at the National Capital Commission, calling them “dangerous” because of their speed and weight.

There are two types of electric-assisted bikes. One resembles a traditional bicycle with a battery attached to the post, while the second version, called an eScooter, looks like a small motorcycle. While this seems like an obvious distinction, cities often classify most forms of two-wheeled transportation under the same category. The City of Ottawa currently lumps data for e-bikes and traditional bikes together. Because different rules apply to different kinds of bikes, the city’s thinking makes accident data ambiguous.

E-bike riders aren’t required to have a licence or insurance, and are allowed many places buzzing with pedestrians and other cyclists. This has people crying foul over the safety implications, saying the legal requirements of being over 16 years old and wearing a helmet aren’t enough.

With the growing number of e-bikes on the streets, do cities need better safety regulations?

In 2012, the NCC took a step in this direction, banning eScooters from their 236 kilometres of pathways. The City of Ottawa’s e-bike regulations, which took effect in 2009, allow scooter-type bikes on bike lanes that are physically separated from pedestrians as long as they don’t interfere with other cyclists.

Before the 2012 ruling, during the NCC’s public e-bike consultations, many people said that weight and speed concerns were put to rest by the powered brakes that come installed on e-bikes. Still, the NCC decided that if the line wasn’t drawn, it would open up the pathways for other motorized vehicles.

“The NCC was facing a situation where there were e-bikes on the recreational pathways, so there became a need for a policy,” said Jasmine Leduc, a spokesperson for the NCC, saying that e-bikes are often twice the weight of traditional bikes and their speed can exceed the pathway limit of 20 km/h.

Electric bikes have a maximum speed of 32 km/h, which many athletic cyclists can reach without a motor. But because they are heavier than regular bikes, with many eScooters weighing in at a whopping 75 lbs, the damage sustained in accidents can be worse. An e-cyclist died this January in the Byward Market after his scooter was hit by the opening door of a parked car.

But does putting scooter-type e-bikes on the roads really make things safer?

Even the changes proposed in Ottawa’s 2013 cycling plan–like wider bike lanes–make few accommodations for motorized bikes, often forcing them into traffic with vehicles bustling by at nearly double their speed.

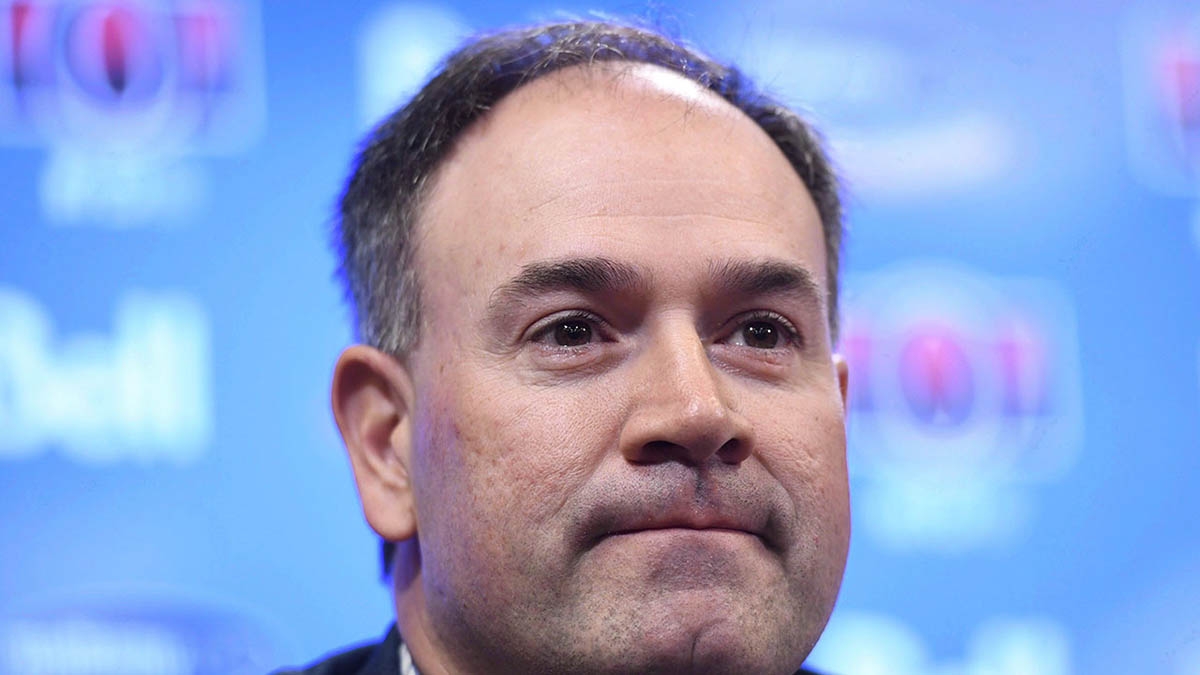

In recent years, city planners have been making sizable leaps in improving bike safety. “We’re spending more money on cycling than we ever have before,” said Keith Egli, the City of Ottawa transportation committee chair. In fact, the city plans to invest some $110 million in cycling infrastructure, such as bike lanes and “complete streets”–roads with designated space for all users– until 2031, according to a 2015 report by the cycling advocacy group Bike Ottawa. But even with these investments, cycling and e-cycling aren’t necessarily getting safer. There were more than 270 cyclist injuries due to collisions in 2013, up 17 per cent from the previous year, according to the City of Ottawa’s Road Safety Reports.

A 2015 report by the Pembina Institute found that there were three collisions per 100,000 cycling trips in Ottawa, compared to Vancouver’s one. Given the population, if every person in Ottawa got on a bike, there would be 27 collisions every day.

Don Grant, executive director of the Ottawa Centre EcoDistrict, a group advocating for an environmentally sustainable city centre, blames the city’s patchwork of bike paths for the collision rate. Ottawa’s paths don’t connect into a continuous corridor, forcing riders onto busy roads when their lane abruptly ends. Last year the EcoDistrict mapped 20 popular cycling routes around the downtown core. “None of them were (cycle-safe) infrastructure from start to finish,” Grant said. “They’re not safe enough that you would feel comfortable letting your sixth-grader ride their bike along these pathways.”

The year Julie Albers bought her e-bike, she was “doored” by a parked car. Her pedal and mirror were slashed off and the impact spiraled the bike around 180 degrees before slamming her into the body of the car.

The knee-jerk reaction is to build more bike lanes, but Egli said there isn’t always enough space on the existing roads for bike lanes, though the city is trying. And since scooter e-bikes are banned from pedestrian-populated lanes, you’ll still have cyclists on the roads.

“Cycling can’t be seen as just a parallel activity to someone in a car who just presses a pedal,” said Andrew Furman, a cycling infrastructure specialist at Ryerson University. While the government of Ontario has ruled that cyclists behave like cars when on the roads, Furman thinks that’s a dangerous message to send. “As a cyclist if you really pretended you were a motor vehicle, you wouldn’t survive very long,” he said.

Despite these safety concerns, the benefits of cycling outweigh the risks by 20 to one, estimates Dr. Chris Cavacuiti in a 2013 cycling injury report by the University of Toronto. Cyclists seem to agree with Cavacuiti as the League of American Bicyclists, a cycling advocacy group in the U.S., found that 80 per cent of cyclists thought e-bikes were a great mode of transportation.

“E-bikes aren’t that much different from regular bikes, but people get intimidated by (the term) ‘electric’, said Claudio Wensel, co-founder of Pedal Easy Electric Bikes in Ottawa. “As soon as people get on the e-bike, they realize it’s no different from what they’re used to.”

Related: Ten Reasons to Start Biking this Spring.

It’s not just the American market that’s booming. China produces over 30 million e-bikes annually, and Europe was enthusiastic about the bike early on. Many cities worldwide are taking after the Netherlands in integrating e-bikes into daily life by offering free parking and public charging stations as incentives for e-bike users.

Egli and the Ottawa transportation committee recently met with infrastructure specialists from the European nation to discuss how to build better cycling infrastructure. Even with this progress, it will be a slow ride to Ottawa’s 2031 goals – “complete streets” and bike lanes– to better protect cyclists.

For e-bikes, building the market in Canada will be an uphill battle. According to a 2013 survey by the City of Toronto, the majority of respondents want a distinction between scooter and conventional e-bikes to make sure each gets their respective –and different– safety regulations. For example, people thought e-bike riders should require a licence and insurance, but almost all respondents said e-bikes should be encouraged as environmentally friendly transportation.

The future of Ottawa cycling is bright. A 2011 StatsCan survey found that more than six per cent of trips made in the Ottawa-Gatineau area were on bikes, landing the nation’s capital in the top five per cent of cycle-savvy Canadian cities.

Though e-bikes are still trying to safely find their place on roads, cycling experts like Furman are optimistic that e-bikes will be worth the time and resources. “It’s about planting those seeds for the next generation,” he said.

Article by Elise von Scheel.