The humble beginnings of Canada’s professional public service

There was no public service as we understand it today prior to the advent of responsible government. The administration of colonial territories under both the French and British regimes was simple. The civil and judicial needs of a sparse population in remote outposts like Detroit would have been addressed by a parish priest, military officer, or even a doctor if there was one. Jesuit Father Antoine Laumet de la Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, for example, arrived at the Detroit River outpost in 1701 and served as the first official representative.

Under British rule, Lt. Gov. John Graves Simcoe used the new powers of the 1791 Constitutional Act to build a system of English common law, with its courts, trial by jury, and freehold land tenure. Simcoe installed a tight clique of conservative members of the Church of England to administer Upper Canada from York. The belief was that Toryism was conducive to social order and cohesion, versus the fledgling democracy in the American republic that led, lest they forget, to mob rule and social turmoil. The invasion of 1812 only reinforced that world view.

The population of Upper Canada was ethnically, linguistically and denominationally diverse and so it was the intension of Simcoe’s appointees and friends to establish a ruling class that favoured England. The elected Legislative Assembly was effectively powerless, with the unelected appointees being answerable only to the lieutenant governor. The whole affair set in place the conditions for what eventually and pejoratively became known as the Family Compact. It stood firmly, albeit occasionally rattled, from 1792 to 1837 as a system of political patronage.

Religious clerics arrived in new settlements bearing the responsibilities for guiding both the souls and the minds of their flocks. Curriculum provided moral and social instruction and was based on the particular theological framework of their respective denominations. The Reverend William Bell of Perth, for instance, was preacher, teacher, and moral arbiter to those of the Presbyterian faith, while conferring on broader issues with neighbourly Protestant missions. Roman Catholics tended to their own turf in what evolved into a separate school system, and Anglicans had what was generally felt to be an official status with aristocratic leanings. Public education and the required tax base and funding was still a long way off.

In the early 19th century, individuals started most schools as business ventures tied to the needs of production. Classes often met in private homes where pupils were also tasked with maintenance labour. By the 1840s, grammar schools averaged fewer than 30 pupils and one or two teachers. As the economy grew, so did funding from the public treasury, and, along with it, a more standardized curriculum and school year. New incentives were put in place to support construction and maintenance. By 1846, Egerton Ryerson, a Methodist minister and educator, openly challenged the Family Compact of John Strachan and toured Europe extensively to study alternative systems of education. His 1846 report on a system of elementary instruction advocated for free and compulsory public education in Canada West. The ensuing legislation formed the basis of Ontario’s school system and the democratic mandate of a new Ministry of Education.

the Act also favoured the hiring of anglophone men."

The Province of Canada was established in 1840 and Sir Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine became the first leader of a responsible government in Canadian history in 1849. Political and non-political officers of government were separated in theory, but normal practice was political patronage appointments to the emerging civil service along party lines. Along comes Confederation and the constitution of a federal government in which the same patronage system held firm for the next fifteen years.

Tour guides earnestly point out that Ottawa’s original Parliament Buildings housed the entirety of national affairs, the largest departments being Agriculture, the Post Office and Customs and Excise. Patronage was one of the main functions of government, both for appointments to public office and for government contracts. It took scandals and accusations of ineptness to bring about the Civil Service Act 1882 and a Board of Civil Service Examiners. Applicants were screened for literacy and little more, meaning if you could work a pen, you were in. There was no tenure system for civil servants, although senior ranks tended to remain in their roles when a change of government occurred. Pensions and other benefits were unimaginable.

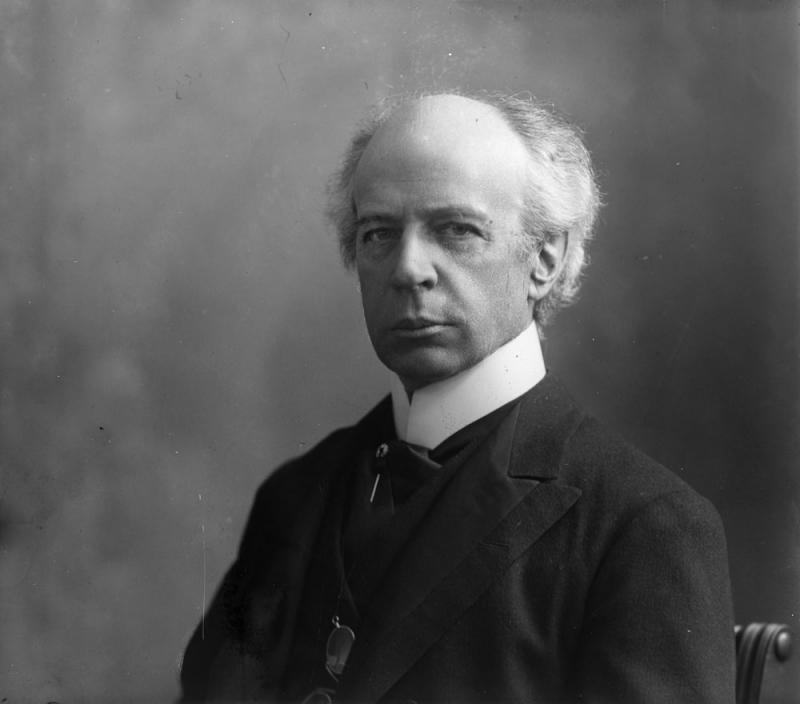

Patronage seriously hampered continuity in the development and implementation of government policy. There were six civil service inquiries between 1868 and 1913. The first genuine attempt to reduce and eventually eliminate political patronage came when the Laurier government eliminated the official patronage lists in 1907 and passed the Civil Service Amendment Act 1908. Appointments of department officials were thereby made according to a merit system and competitive examinations. It wasn’t perfect, but the Act did bring about conditions similar to those in the British civil service.

11,000 civil servants resigned or were removed in 1911 under the Borden government due to patronage legacies, but political influence was tenacious and internal lobbying resulted in the exception of a significant number of offices from the oversight of the Civil Service Commission. Its commissioner resigned in 1917. Additionally, reform was seriously disrupted with the coming of the Great War and the rapid growth of government. Borden’s Union government of 1917 beefed up job qualifications with the Civil Service Act 1918 amendment; the Act also favoured the hiring of anglophone men. The Commission now oversaw all service hirings and shared, with deputy department heads, greater control over appointments and promotions.

The Civil Service Superannuation Act 1924 established the first real public service pensions to encourage retention and attract professional applicants. It was the beginning of today’s career-based public service, replete with job security, benefits, and perks. The federal civil service was by and large seen by the general public as being competent, professional, and respectable.

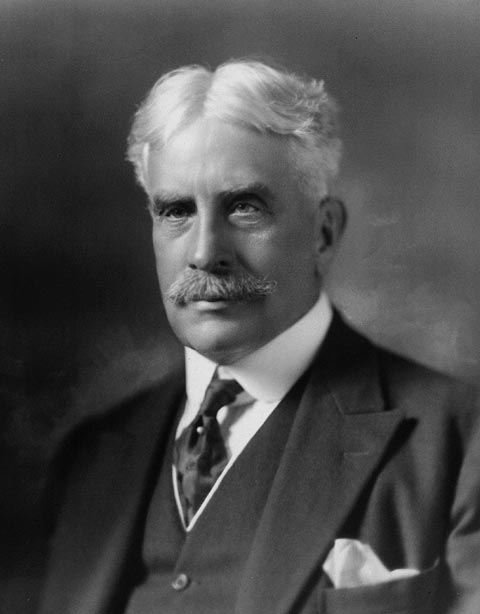

The growth of Canada, its federal government and its civil service necessitated a more centralized approach to government spending. R. B. Bennett created the Consolidated Revenue Fund and establishing the Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury in 1931. Spending bills were now the exclusive domain of Parliament itself and subject to its approval alone. It was a measured response to the demands of the Great Depression but made for a sluggish system which must have resembled Harper’s Accountability Act by which blowing one’s nose requires sign-off. Things were again fine tuned in 1932 with the transfer of many staffing responsibilities from the Civil Service Commission to the Treasury Board.

The relationship between Cabinet and the civil service was loosely structured and improvisational. There was no secretariat and the decision-making process was completely under the thumb of the PM. But WW II made it imperative to streamline communications with the civil service during a rapidly growing and complex set of government roles and responsibilities. The fix came in 1940 with the establishment of the dual role of Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet. Prime Minister Mackenzie King named his principal secretary Arnold Heeney to the job. Heeney was a Montreal-born lawyer, diplomat, and consummate professional civil servant. He set about establishing a Secretariat to the War Committee of Cabinet by which Heeney provided organizational support to the PM and became the de facto Head of the Civil Service, a role that would be made official in 1992.