The master plan for the growth — A Plan for the Capital

By Katharine Fletcher

Capital cities are fortunate entities. Their unique role is to symbolize a people's concept of nationhood. As such, they present particular challenges to planners. Ottawa is no exception.

Does Ottawa and the National Capital Region (NCR) embody a sense of Canadian-ness?

Marcel Beaudry, chairman of the National Capital Commission since 1992 thinks so.

"Ottawa and the surrounding region truly reflect a 'Canadian-ness,' he says. "In fact, it can be considered a living reflection of our collective Canadian identity. The diverse and rugged landscapes epitomize the geographic variety of our vast country. Set against this backdrop of flowing rivers and magnificent green spaces, today's Capital is home to Canadian institutions, world-class museums and monuments of national significance of which we can all be proud."

But Ottawa wasn't always beautiful. Bytown started life as a rough, boisterous and ugly lumber town.

Nonetheless, Queen Victoria chose Ottawa as the capital of Canada, in 1857. So, down came the army barracks on Barrack's Hill, to be replaced with the vaulting spires of Parliament, in 1866.

But Gothic grandeur doesn't automatically translate to splendour in the city. As Sandra Gwyn noted in The Private Capital, residents of Sandy Hill — including Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald — were disgusted with the stench of sewage from the drains. "Not until the arrival of the sewers in 1874" could residents "at last relax and inhale luxuriously," Gwyn wrote.

By 1899, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier looked about the capital in dismay, noting: "I would not wish to say anything disparaging of the Capital, but it is hard to say anything good of it. Ottawa's not a handsome city and does not appear to be destined to become one either."

Laurier exclaimed it was time to beautify Ottawa, to transform it into the "Washington of the North." He might well say that, for as early as 1791, planning of Washington's Federal District ws underway.

Pierre Dubé, the NCC's chief of urban planning, says that this plan, rendered by Pierre L'Enfant, "incorporated sweeping boulevards, public spaces with monuments to the nation's grand vision, links to the adjacent waterfront and well-designed residential neighbourhoods."

With Washington's plan in mind, Laurier determined to create a planning body for the capital. The Ottawa Improvement Commission (OIC) was created in 1899, the forerunner of today's National Capital Commission.

You cannot live in Ottawa for long without being aware of the NCC, as the Commission is known. It's everyone's favourite scapegoat. But before we pass censure, let's walk a mile or so in their planning shoes.

What does it take to plan a capital? "A respect for the function of a capital city," says Dubé. "The OIC recognized the first task was to start planning the capital."

Montreal landscape architect Frederick Todd created Ottawa's first plan, which the OIC published in 1903. His focus was beautification: He envisioned Lady Grey Drive (a grand roadway linking Rideau Hall to Parliament), King Edward Boulevard, Rockcliffe Parkway, and the protection of some woodlands that now comprise Gatineau Park.

But there was still no overall master plan for the growth of the capital. Todd wrote, "You may ask, is it reasonable to look so far ahead as one hundred years or more, and to make plans for generations in the distant future? We have only to study the history of the older cities, and note at what enormous cost they have overcome the lack of provision for their growth, to realize that [their] future prosperity and beauty … depends in a great measure upon the ability to look ahead, and the power to grasp the needs and requirements of the great population it's destined to have."[Frederick Todd Report, 1903]

Not everyone was enamoured with the OIC's plans, and it had no jurisdiction to implement the coordinated network of parkways that Todd envisioned.

In 1912, urban planner Edward Bennett was hired and in 1915 the Holt Report was tabled in the Commons.

Bennett said a Federal District was required. He also suggested a park should be created in the Gatineau Hills, and identified the steam train and railway yards as Ottawa's most severe urban blight.

"Bennett's plan was well received," said Dubé, "But it suffered from bad timing: WW I started in 1914."

In 1927, the sixtieth anniversary of Confederation, the Federal District Commission replaced the OIC. The name change was key: It married Todd's vision for a long-term plan with Bennett's recommendation for a capital region.

In fact, the Federal District Commission reflected not just Washington DC, but other nation's capital districts. For example, Australia's Canberra benefited from planner Walter Burley Griffin's plan (1903-08). Dubé notes, "His plan symbolized democracy and reflected the values of an emerging nation. It complemented the natural features of the site, setting the city within the landscape."

However, whereas Griffin's was a "design-build" capital plan, Ottawa's planners never enjoyed the same luxury. Ottawa already existed, so our early capital planners had a more complicated task that today's planners inherited. How to build the parkways and create Gatineau Park when land was already owned and had other functions?

During this unprecedented time of growth, the FDC undertook Confederation Square, built Champlain Bridge, created Jacques Cartier Park, and started land acquisition in earnest for Gatineau Park.

In the middle of the FDC's reign (1927-1958) came the Second World War. By 1936, prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had already met Parisian urban planner Jacques Greber, the chief architect of Paris' World Exposition of that year.

"King invited Greber to Ottawa to advise on planning the capital, and Greber spent two years here. It's he who advocated the decentralization of government workers into Tunney's Pasture," said Dubé. "But 1939 saw the outbreak of World War II. Nothing happens in the capital until 1945. Greber returned to France."

A huge debate on how to commemorate the war effort marked the post-war years. "The war memorial was as hot an issue in its day as our NCC Metcalfe Street plan is now. Check the papers!" Dubé smiles, acknowledging the rancorous debate over widening Metcalfe to provide a grand approach to Parliament Hill. "After the war, King re-invited Greber, and the planner accepted, but only on the condition that he would act as an advisor amid a team of Canadian planners."

In 1950 the team produced the Greber Report properly titled A Plan for the Capital, tabled in the House of Commons in 1951. It recommended five major points: removal of the railway tracks from the downtown core; decentralization of government offices to nodes in Tunney's Pasture and Confederation Heights; creation of the Greenbelt (modelled after such European cities as London and Stockholm); extension of parkways and pathways; and the enlargement of Gatineau Park.

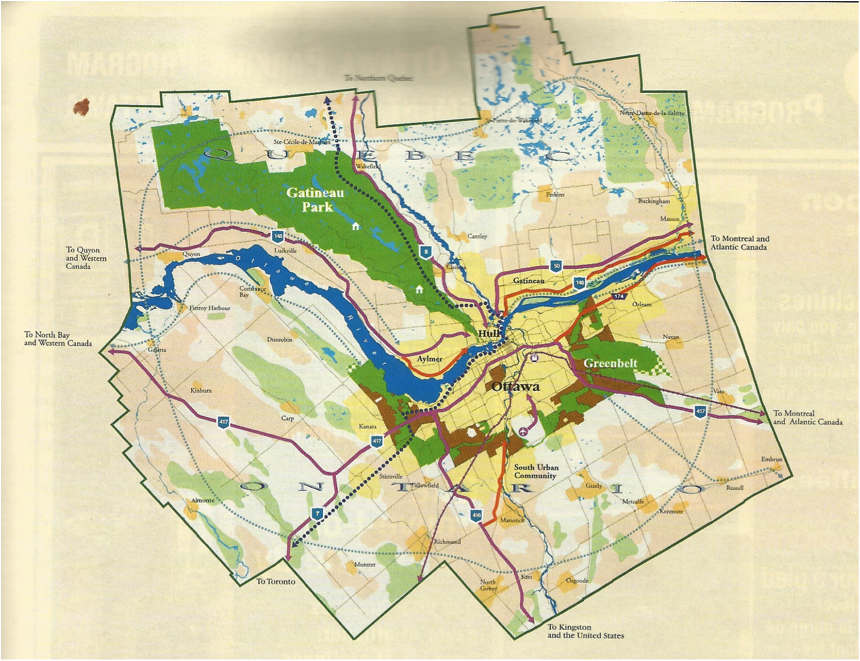

With the creation of the Greenbelt and Gatineau Park, today's NCR took shape. When Parliament passed the National Capital Act in 1958, the NCR expanded from 2,300 to 4,660 square kilometres, spanning both sides of the Ottawa River.

A Capital in the Making (NCC publication, 1998) notes, "The Act empowered the National Capital Commission to: acquire, hold, administer or develop property; to construct, maintain and operate parks, squares, highways, parkways bridges, buildings and any other works;…" (page 34)

"By the 1960s, the NCR was essentially as it is today," says Dubé.

But although today many of us enjoy trails in Gatineau Park, or driving east on Sussex to Rideau Falls along the pretty parkway, today's beauty has come at a significant cost.

George Whissel, a volunteer with Doors Open Ottawa this past May, an event which saw Ottawa's architectural gems opened up for public inspection, explained how his family was affected by NCC planning. When Sussex Drive was developed in the 1960s, Lowertown families were "relocated"… a euphemism for forced moves.

Where do you think his father, mother, and his 10 siblings moved? Ironically, to LeBreton Flats, another blue-collar worker's neighbourhood that would be demolished later, forcing yet another move.

Planning is fraught with contention, and Dubé recognizes this. "By the end of the 1970s, the creation of the regional governments and their jurisdictions meant that the picture had changed. The RMOC (Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton) was created in 1978; the ORC (Outaouais Regional Community) in 1979.

Their creation explains why the NCC was unsuccessful in producing Towards Tomorrow's Capital, its1974 plan was coldly received. Mr. Dubé frankly admits: "It contained too much interference in the regions' responsibilities like infrastructure and transportation."

He recalls the protests in Hull (now Gatineau), when workers' homes and churches were expropriated and demolished to make way for Les Terrasses de la Chaudiere, and then the Place du Portage four-phased complex. "Politicians were happy," he said, "because it was a way of 'beautifying' Hull. But it was parallel to LeBreton Flats."

Meanwhile, the 1970s through 80s were important for the NCC as extensive work was done in the core. In the early 1980s, the main recommendations of the Greber Plan were completed.

The Federal Land Use Plan was introduced in 1988, under Jean Pigott's chairmanship (1984-1992). Its emphasis was upon creating pride and unity in the NCR. Under her mandate, the triple crown of "programming, interpretation and national celebrations" was instigated. The NCC hoped this would create symbolic events and programs for all Canadians, and make Ottawa the "home away from home for all Canadians."

Also in the late 80s, the NCC undertook its first survey of how Canadians felt about the role of their capital. Responses helped create the Symbolic Capital, with programming such as the Sound and Light show on Parliament Hill. In 1992, to celebrate Canada's 125th anniversary, Canada House was built to showcase Canadian accomplishments.

That year, Marcel Beaudry was appointed chairman of the NCC. By the mid-nineties, the federal government underwent tremendous downsizing and the NCC suffered major cuts. 600 staff positions were lost.

Nonetheless, a new plan was developed, called The Core Area Concept of Canada's Capital. "The underlying goal for the Core is to express the vitality of the area and the reinforcement of exchange between the federal and city aspect of the Core Area on both sides of the Ottawa River."

What does that mean? Well, unless you've been fast asleep, you know that it emphatically does not involve the widening of Metcalfe Street, which has been abandoned due to public pressure.

But if you get a copy of the Core Area Concept, you'll find a comprehensive planning vision for the capital's downtown sector. Six areas are targeted for development: LeBreton Flats, the Victoria and Chaudiere Islands, Sparks Street Area; Connection to Gatineau Park; the Bank Street Axis (with a plan for extending the road and creating access to the Ottawa River); and the "Industrial Land" of Scott Paper, in Gatineau.

The latest LeBreton Flats plan has taken 15 years to develop. Now destined to be the home of another symbolic Canadian institution, the War Museum, the former industrial site is being decontaminated.

Fortunately, since 1990, the Canadian Environmental Impact Assessment Law is in place to ensure that environmental considerations are examined prior to such development. Every NCC project now falls under its scrutiny. But although it undeniably marks progress, many residents are sceptical, perceiving that developers' plans appear to win over environmental issues. Case in point was the extension to the McConnell-Lariamee Parkway in Gatineau that proceeded, despite the destruction of old growth pine forests.

So, what do we all think of the NCC at the end of the day?

Is it a Commission out of control?

Or is it an organization that's fraught with challenging decisions to be made, about how to shape our capital in partnership with the cities of Ottawa and Gatineau?

Final word to Dubé.

"People today seem to have more understanding of the NCC's role, and of planning. It's important to want the capital to be an object of pride for Canadians. We're not just building a capital for residents of Ottawa and Gatineau. Americans passionately love Washington and want to visit their institutions there. We should be proud of Ottawa, our capital. I've just returned from visiting Canberra, where I met with members of its National Planning Authority. They are very interested in Canada's soft programming, in how we bring people into our capital."

Does Ottawa symbolize our Canadian-ness? How successful is the NCC in defining our Capital's role? No one can say.

One thing for sure: If you want the ultimate challenging profession, join the NCC and become a planner.