The Rhythms of Life

Family Furnishings:

Selected Short Stories 1995 – 2014 Alice Munro

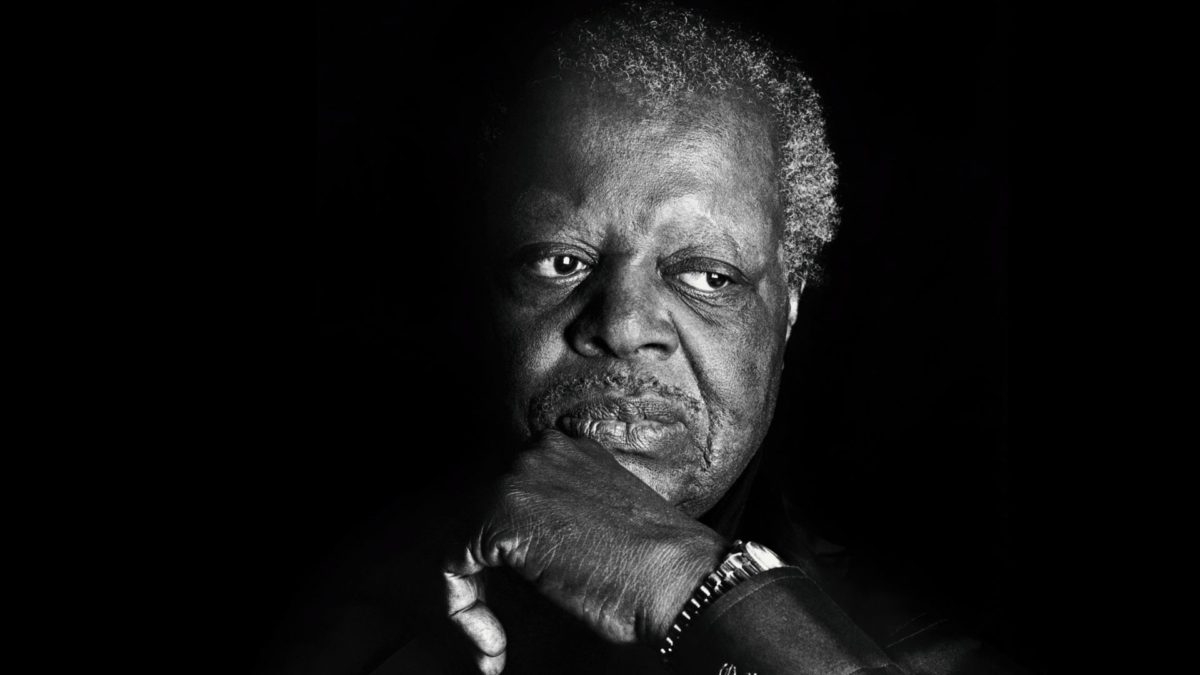

Reviewed by Don MacLean

May 2015

The short story can sometimes seem in jeopardy of being forgotten if not dismissed. This danger is not at all due to a dearth of this particular form of storytelling. Countless are written and many gems are to be found, but most are to be discovered in magazines or literary anthologies and not on book store display tables. Next to a great novel, the short story can seem inadequate, like a promising seed that doesn’t quite fully bloom. Alice Munro, perhaps more than any other writer living today, has restored the short story to its rightful place as an art form every bit of worthy as a novel of our praise and devotion. She was awarded the Nobel Prize last year as a way of marking a lifetime of this sort of literary achievement. The prize

was given just as Munro appears to be quietly retiring from the writing life. The recent publication of Family Furnishings: Selected Stories 1995 – 2014 thus seems particularly fitting. Taken together, the stories constitute a wonderful sampling of Munro’s remarkable range as a storyteller.

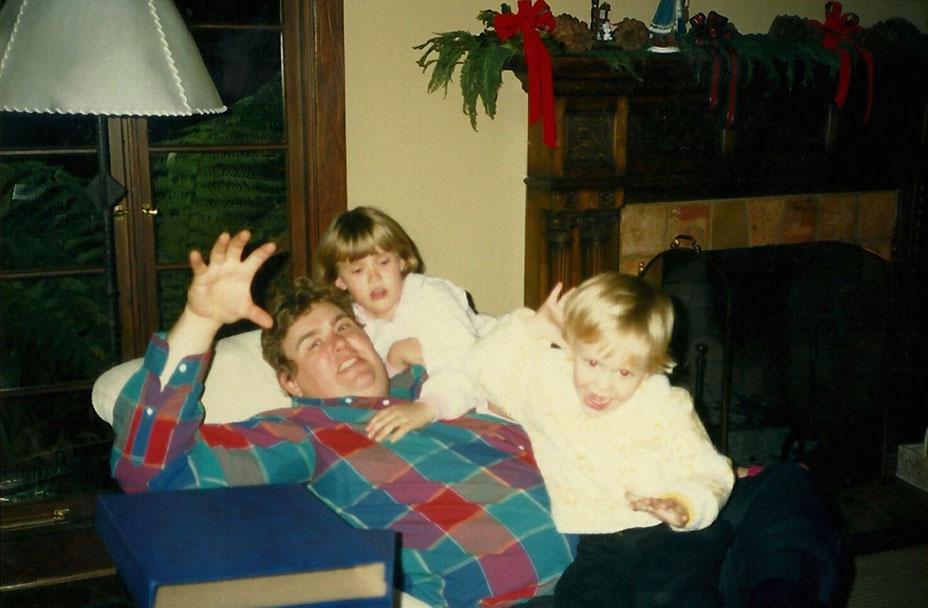

Part of Munro’s genius is her ability to mine beautifully but without sentimentality the sudden, unexpected and sometimes violent up ending of life’s rhythms. Many (but not all) Munro stories take place in the past and her characters almost invariably lead ordinary lives, sometimes in urban centres but more often in small Canadian places like Ottawa Valley or Huntsville, Ontario. The effect is to evoke times and places that may seem increasingly remote. Yet her characters’ experiences will resonate with readers with a modern sensibility. A chance encounter precipitates unanticipated yearnings. A seemingly innocuous mishap initiates a lives shattering chain of events. A sudden loss yields deeper insight into the nature of the human experience. A marriage proposal is retracted at the last possible moment. The lives of characters are irrevocably changed or damaged by these sorts of unforeseen developments. But out of the carnage and emotional upheaval emerges another rhythm.

“The Love of a Good Woman” begins with the sort of dramatic discovery we don’t necessarily associate with a Munro story. Three young boys come across a dead body in the river, that of Mr. Willen. H e’s in his vehicle, submerged in the water. We don’t know how he arrived at this most unfortunate end, but we trust all will be revealed in good time. Even though Munro is the master of the short story, she still demands patience of the reader. The story’s main character is Enid, an unmarried woman heading toward middle age. She ends up caring for a woman – Mrs. Quinn – in her final days. Shortly before she dies, Mrs. Quinn makes a grave admission. In addition to being an optometrist, Mr. Willen was something of a pervert. When checking her eye sight during a house call he would make unwanted advances. On one such occasion her husband finds Mr. Willen with his hand up his wife’s skirt. This is a moment when life’s rhythm is violently overturned by a sudden wave of rage. The husband lets loose on Mr. Willen; after the wave has passed Mr. Willen is dead.

e’s in his vehicle, submerged in the water. We don’t know how he arrived at this most unfortunate end, but we trust all will be revealed in good time. Even though Munro is the master of the short story, she still demands patience of the reader. The story’s main character is Enid, an unmarried woman heading toward middle age. She ends up caring for a woman – Mrs. Quinn – in her final days. Shortly before she dies, Mrs. Quinn makes a grave admission. In addition to being an optometrist, Mr. Willen was something of a pervert. When checking her eye sight during a house call he would make unwanted advances. On one such occasion her husband finds Mr. Willen with his hand up his wife’s skirt. This is a moment when life’s rhythm is violently overturned by a sudden wave of rage. The husband lets loose on Mr. Willen; after the wave has passed Mr. Willen is dead.

What is Enid to make of this unexpected revelation? She’s initially persuaded that the husband must be horribly conflicted. You cannot live in the world with such a burden. You will not be able to stand your life. She imagines confronting him with this knowledge. She hopes it will bring him relief, but understands too that it could spur him to another round of violence. The tension rises. But in a Munro short story, life has a way of imposing its rhythm and in so doing dissolving any such tension. Enid begins to imagine that Mrs. Quinn’s story was all “lies.” It’s possible, but convenient too. For it allows another idea to spring to life inside Enid’s mind.

The different possibility was coming closer to her and all she had to do was keep quiet and let it come. Through her silence….what benefits could bloom. For others and for herself. This is how to keep the world habitable.

There are larger social forces at work in a Munro story – war, immigration, disease – but they are almost always in the background. Munro is more interested in the subtle developments that shape a life or change its direction. One exception to this admittedly loose rule is the haunting “The View From Castle Rock.” In it Munro tells the story of an extended family’s crossing of the Atlantic to begin their new life in Canada in the early stages of the nineteenth century. There is the patriarch – Old James, as he’s called. He’s crossing with his sons Andrew and Walter and Andrew’s wife Agnes and their 2 year old son James – Young James, as he’s called. Mary is James’ childless daughter who looks after Young James while on the ship.

Munro is a master at capturing – often in a line or two – the competing spirits of the time in which a story takes place. Across the Atlantic, Old James declares to his sons after too much to drink, is America, a land so abundant that even the ‘beggars are rich.’ This distorted sense of abundance and possibility is tempered by the family’s immediate challenges and their powerlessness in the face of cruel realities. Conditions on the ship are cramped and uncomfortable. Lives are often short and demanding. Indeed many children arriving in Ontario or Quebec, the reader discovers, won’t reach adolescence, let alone adulthood. They will instead be:

Dead of some mishap in the busy streets of York, or of a fever, or dysentery — of any of the ailments, the accidents that were the common destroyers of little children in his time.

In different ways, the story anticipates other transitions. Agnes doesn’t so much lament as resign herself to the same sort of fate she would have lived had they stayed in Edinburgh. She’ll have babies and help her husband maintain a farm. Choices for women will be longer in coming. But old James’ sons will start to entertain other possibilities. Walter writes of the family’s passage while on board the ship. His efforts are meant to document the experience, but they also constitute an unanticipated discovery. Walter learns to love the written word. On board the ship he seeks out spaces away from his family and in so doing comes close to a young woman making a similar journey with her father.

Yet the story is not without those more subtle moments that shape a character’s life that are Munro’s stock in trade. At one point Young James goes missing on the ship while under the care of Mary. Fearing the worst, Mary has a haunting epiphany.

Everything in an instant is overturned. The nature of the world is altered…

This is what Mary plainly sees, in those moments of anguish – that the world which has turned into a horror for her is still the same ordinary world for all these other people and will remain so even if James has truly vanished.

Mary, in this moment of stark clarity, not only sees how a life can without warning be so arbitrarily and tragically upended. She understands why that experience is often so lonely and alienating. Just as quickly as Mary is drowning in this dread, however, the moment passes. Young James is found, safe and unharmed. Life’s rhythm reasserts itself.

Occasionally hardship leads to self revelation, as it did for the young protagonist in “Hired Girl” or the narrator’s father in “Working For a Living.”

One night somebody asked, when is the best time in a man’s life?…

My father spoke up and said, “Now. I think maybe now.”

They asked him why.

He said because you weren’t old yet, with one thing or another collapsing on you, but old enough that you could see that a lot of things you might have wanted out of life you would never get. It was hard to explain how you could be happy in such a situation, but sometimes he thought you were.

In a Munro story such moments of self awareness or happiness are hard earned but often felt in an ambiguous sort of way. They also tend to be fleeting. For once experienced they’re submerged in the larger rhythms of life.