The spectacularly awful leaders’ debates: causes and a remedy

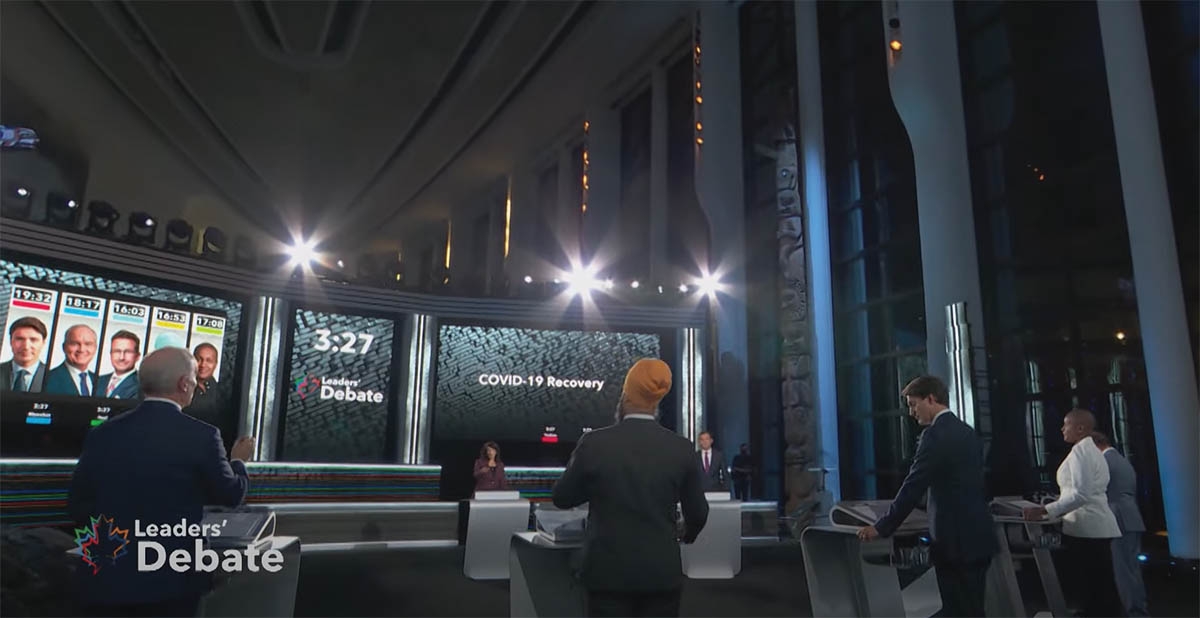

Photo via CBC NEWS

Now that a discrete interval has passed since our recent federal election, it is an opportune time to try a bit of dispassionate analysis to explain to ourselves why it felt like such a shambles. It launched amidst some controversy over whether it was needed at all, but it seems to me that it didn’t entirely become a festival of mutual ox goring until the so-called leaders’ debates.

Something very odd has happened to the word “debate”, if those leaders’ debates are anything to go by. Perhaps it’s my inner curmudgeon speaking, but through most of my life, there were two incontrovertible properties of a debate. The first was that all the debaters were expected to speak about the same subject, and the second was that each side had a substantial reserved block of time to elaborate their position (and sometimes more than one block) and a further consolidated block of time for rebuttal. Interruptions by opposing debaters were usually heavily penalized.

The first of the two debates in French had a hint of the original definition of “debate” in its structure, despite the woefully short time blocks. It was conducted with considerable decorum (with only odd exceptions), and the referee (called a “moderator” to mollify the media folk) was respectful, helpful and not especially intrusive. The participants were expected to address the same topics.

By the time we reached the sole English-language debate, the concept had transmogrified itself into an egregious caricature of a sort of demented collective press scrum. The central focus was on the so-called moderator, who peppered each of the leaders with different questions, allowing seconds, rather than minutes, for an answer. It felt more like the interrogation of captured spies than a debate.

But enough about the dubious features of the event. Amongst my usual interlocutors, I have found none who found it edifying. The more interesting questions are, first, what are the causes of that sort of debacle, and, secondly, what can be done to give us something more useful during future elections.

I suspect that there are many causes for what we saw. It is popular to blame the communications revolution and social media for some perceived decline in the attention span of some folk. I’m not entirely certain that attention spans have declined. People still develop intense interests that evoke sustained concentration on a single subject. But some other causes are fairly obvious. Some portions of the press and media have, over the last two generations, become hugely narcissistic. They have gone from reporting the news to thinking that they are the news, and reporting incessantly on themselves.

Again, perhaps it is the curmudgeon in me that makes me think that journalists were better forty years ago. Given the critical importance of free speech and a free press in guaranteeing democracy, I am relieved that there still are a non-trivial number of exceptional, well-informed and perceptive journalists. But many are not. A significant slice of the fourth estate is neither literate nor numerate, and do us the huge discourtesy of assuming we aren’t either. They are wrong; large swaths of the voting public in Canada are well-educated and somewhat reflective.

Compounding that is the perceived broadcast need to compress complex issues into 10-30 second soundbites. I say “perceived” because it isn’t necessarily true. Newsmagazine shows that take 20-60 minutes on a single issue remain hugely popular.

But if some in the media give new depth to the word “shallow”, are leading politicians similarly limited? Admittedly, some politicians and their media advisors have bought into the “soundbite” myth. The result is scenes of political leaders spouting snappy “talking points” and catch phrases, instead of marshalling evidence and outlining their logic. But that doesn’t mean that they are all incapable of serious, reasoned debate.

I’ve known many Canadian politicians, including three PMs, seven party leaders who did not become PM and dozens of members of Parliament or senators who were cabinet ministers, and certainly more than half are or were genuinely impressive in private.

So just imagine an election debate in which unelected journalists didn’t participate, and didn’t interrupt our representatives every 30 or 60 seconds. Imagine candidates debating each other in long enough blocks to be coherent, and on subjects which they think we might wish to hear about before we judge their fitness to govern. After decades of watching news anchors and reporters tampering with debates under the guise of being moderators, contemplate the possibility of political discourse not pushed through microcephalic filter of some ill-educated stage prop of a newsreader.

We might get political discourse appropriate for a free people, and I have no doubt that a critical portion of the swing vote would have the knowledge, powers of reasoning, and attention span to assess it properly.

So how can the trend be reversed? Is it possible to get from where we are now to a more civil and substance-oriented debate? Perhaps.

Ironically, the Covid pandemic may just have begun a series of cultural changes that may make such debate more possible. Two important changes in our culture are the public’s wariness of crowded in-person events, and an increasing familiarity with on-line events, some of which are interactive. Neither of these trends is likely to be a transient.

This could somewhat reduce the attraction and utility of “whistle-stop” campaigning across the country by party leaders and put more emphasis on broadcast or internet-based events, of which there would logically be more of them and longer ones. That opens the door to a much more extensive series of debates, and that is the crucial key to making them better.

More debates means that each one can cover a single topic, or at least a narrowly defined group of topics. More debates also means that not every leader needs to be in every debate. Some debates might even be in the traditional format of only two sides in the debate. Furthermore, an extended series of debates provides an opportunity to appropriately scale the participation of party leaders whose parties have not achieved official party status in the House of Commons. Leaders of parties below the official party cut-off could be invited to participate in perhaps one or two debates in each official language, and all the others could be invited to many more, though not to every one.

Such a framework would lend itself well to a format that gives individual debaters non-trivial blocks of time, and would push the leaders to make more detailed arguments, and to marshal facts and data to support their stances. It might also allow for two-person teams, especially when the topic of the debate is one that falls primarily within a single cabinet portfolio. Imagine a debate, for example, on health policy issues, with the sitting PM and the Minister of Health on one side, and the leader of an opposition party, plus that party’s health critic (or shadow minister, if you prefer the older term) as the participants in a four-person traditional debate. Or, with a couple of opposition parties, that would be six speakers, with each given a couple of opportunities to speak, which is not impossible for a 90-120 minute event.

This approach, with three or four major parties, implies quite a number of debates. But if these debates, rather than whistle-stop rallies, become the central features of the campaigns, that is not an insurmountable problem. The whistle-stop rallies are just a form of targeted advertising, and such advertising can be done without traipsing the leader across the country from riding to riding, (which, as a modern apparent sin, dramatically increases the leader’s carbon footprint). Plus, it is an opportunity for each party to raise the public profile of some of their more local senior MP’s, by giving them some ambulatory public exposure roles during the campaign. For those aspiring to cabinet roles, or who already hold them, this is a great opportunity, and also helps to move us away from the drift to cult of personality politics which has been plaguing the US and some European nations.

I suspect that the real impediments to making such a debate series the centrepiece of election campaigning is that the idea of it will evoke instant revulsion amongst the spin doctors, professional publicists, and campaign advisor hangers-on which burden every party. They will fear that a certain fraction of them will become redundant. And if they are what is standing between the voters, and real transparency in political discourse, their ranks should indeed be thinned out. Replacing some of them with folk who can actually develop and articulate real policy, rather than catchphrases would be a boon to national mental health.

The television broadcast networks as well may not look warmly upon such a significant series of disruptions to their normal broadcast schedule, in which case they may need to be reminded of the effects of the communications revolution, including the existence of the internet and the many other platforms over which such programming could be distributed widely, and in real time.

But you may well ask, “Given the opportunity, can the leaders actually debate effectively?” It is very likely that they can. Of the six party leaders during our recent election, four had trained and worked as lawyers, so they certainly had considerable exposure to the debating which is fundamental to our legal system, with its teachings and methodologies. And of the other two, one had been a drama teacher, so even if he could not prepare a solid debate argument from scratch, he could certainly simulate one quite well, if handed a decent script. The remaining leader was a well-educated individual with a long history of successful entrepreneurship in the entertainment industry, so he likely could cope too.

The role of the moderator thus becomes essentially that of a referee. After delivering a welcoming announcement outlining the scope and rule set of the debate, the moderator’s job should consist of keeping time, discouraging and penalizing interruptions, calling upon debaters when it is their turn, and generally keeping order and decorum. Sort of the equivalent of the speaker of the House of Commons. A key tool for the moderator would need to be a control panel of microphone switches for each participant. Turning off a microphone when debater has gone past the allocated time and not heeded a polite request to wrap up within one sentence is hugely effective for encouraging compliance.

The moderator should not be expected to act as a fact-checker, and should not try to steer the debate content or context. The public, and after-the-fact pundits are the fact checkers, and the politicians should make their own choices of emphasis on the issues, at their own peril.

For our democracy to function properly, real and substantive public debate is essential for making wise choices. And that debating needs to take place in two critical fora. One is in public, so that we can effectively select representatives who will accurately reflect our views and implement our wishes, and the other is in Parliament, where the legislation to carry out those wishes is examined, refined and enacted. One forum, Parliament, already has a long tradition of orderly debate, and a set of rules largely perfected by Arthur Beauchesne prior to his retirement in 1949. The other forum, the public setting of an election campaign, desperately needs an improved form of orderly, comprehensive explanation and testing of competing ideas. In short, we need a coherent and substantial series of real debates, not a couple of playground brawls replete with one-line imprecations from the brawlers and chiding remarks from passers by.

John Scott Cowan is Principal Emeritus of The RMC of Canada