The storied history of 375 King Edward: From Synagogue to Adventist Church

By Reuel S. Amdur

Heading north from Rideau Street on Ottawa’s King Edward Avenue, the major artery that connects Ottawa with Quebec, on the east side you notice some brick buildings. One really hits you in the eye . . . Something is out of place. What is this synagogue structure transplanted from Old Mother Russia doing here?

It used to be Adath Jeshurun Synagogue, built in 1904, but in 1999 the Ontario Conference of Seventh Day Adventists bought it for use by a French-speaking congregation. Now, the home of the Église Adventiste du Septième Jour d’Ottawa, the building has experienced over a century of seventh-day observance.

Originally the synagogue served Jewish immigrant families. Their offspring and other Jews moving to the city joined in worship there till 1957, when that congregation joined with another to form the Beth Shalom congregation to a location further south, as the center of Jewish life in Ottawa had changed. The building then served as a location for memorial services for members of the new congregation who had passed away. That was until its sale to the Ottawa Conference. As it originally helped to welcome Eastern European immigrants to the new country, now it serves as the religious home for new immigrants from Haiti and Africa.

Because of the building’s historical and artistic importance, in 2016 the City of Ottawa declared the structure a heritage building. That designation is both a blessing and a potential curse. It represents an honour but also a heavy responsibility in maintaining this aging structure.

Let’s talk about the origins of the building.

Local Jewish proprietors hired architect John W.H. Watts to design the structure. Later alterations were designed by two other noted Ottawa architects, Allan Horwood and Cecil Burgess. The congregation aimed high when they chose Watts. He was born in 1850 in England and studied in the school of the Architectural Association. In England he worked as a draftsman, surveyor, and evaluator. After he came to Canada in 1873, Thomas Seaton Scott worked as the chief architect for Canada’s Department of Public Works. He proceeded to distinguish himself in a variety of publications and undertakings, including designing fittings for the Library of Parliament, becoming a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art, and the first curator of Canada’s National Gallery. He was the first president of the Ottawa Chapter of the Ontario Association of Artists.

In 1897, Watts established his own architectural firm and developed a reputation for church architecture. Besides Adath Jeshurun, he designed St. Mathews Anglican Church and St. James Presbyterian Church, among others in other cities.

The building on King Edward is immediately recognizable as a synagogue because of the Moorish towers that are in the neo-Romanesque tradition. Romanesque architecture involves a semi-circular or triangular design, the tympanum, over the front portal, along with massive structure with geometrical arches, bulky columns, and simple decoration. The neo-Romanesque style is a modification wherein the structure tends to have arches and windows that are less complex.

Internally, design was in the “arts & crafts” tradition. This movement began in Britain around 1880 and emphasized traditional decoration and craftsmanship and simplicity. Much of that work within the building has been lost over the years, but the windows, with their clear colored borders, remain as a reminder.

During the period when the building served just for the occasional funeral, upkeep was not high on the agenda. As a result, conditions began to deteriorate. For that reason, some members of the Adventist congregation opposed the purchase of the building, fearing that repair costs would be prohibitive. However, the majority was at the time prepared to take the challenge. Now the costs are becoming more apparent.

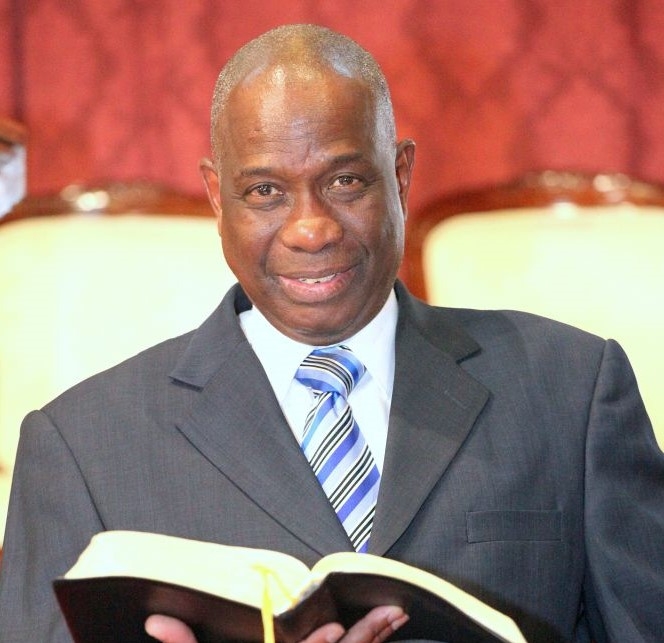

We asked Pastor Nephtaly Dorzilmé about costs, and he responded with some gross estimates. In addition to the typical costs of running a church, in 2019 the congregation put out some $100,000 to replace the decorative stairs and another $30,000 on roof repairs . . . That is just the beginning.

“We need to get a figure for a package of renovations,” he said. The old building requires alterations to make it accessible for the handicapped, probably meaning the installation of an elevator. He has no idea of the potential outlay required for that.

Other undertakings required are renewal of the floor tiles and painting of the towers. As well, the wear and tear over the years has meant the loss of some of the original arts & crafts windows, and their replacement is plain plate glass. Restoring them with replicas of the originals is not even in mind at this point. Yet, from an artistic and historical perspective, it is important.

Then we come to the break-the-bank undertaking: determination of the condition of the foundation. That could run a quarter of a million dollars, and if repairs are needed, it could easily run a like sum. Quite a challenge for a congregation of 560.

The church is showing that it is prepared to do all it can to be good stewards of this heritage site, historical in its role of providing a religious home for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and artistic as an example of a neo-Romanesque building designed by an important Canadian architect. Ottawa provides $5000 a year as its contribution for upkeep, but the costs show that that amount hardly begins to address the need.

In spite of the challenges involved in correcting the deficiencies caused by years of neglect and in ongoing upkeep of this old building, the congregation wants to stay put. They love their building, but they need some help in their stewardship.