Timothy Garton Ash Writes That the EU May Survive, but Some Member States May Lose Their Liberal Character

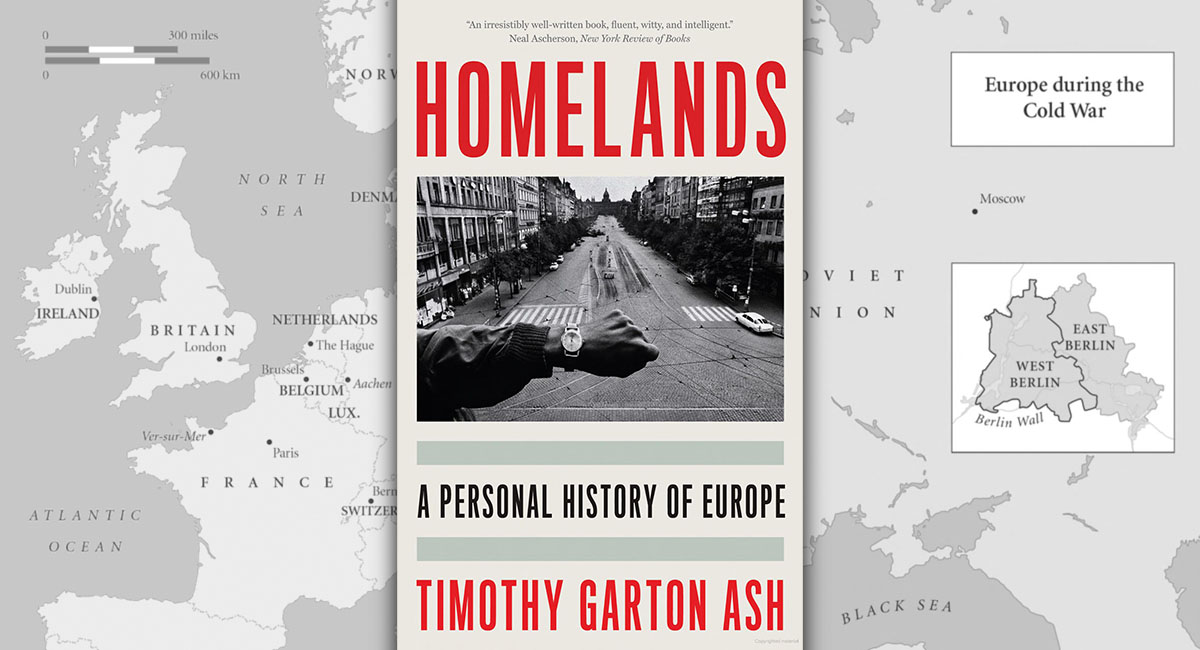

Homelands: A Personal History of Europe

By: Timothy Garton Ash

Publisher: Yale University Press

ISBN: Paperback • 9780300276725, Hardcover • 9780300257076

The past is never dead, it’s not even past. – William Faulkner

“The Memory Engine”

Timothy Garton Ash’s latest memoir, Homelands: A Personal History of Europe, begins with the author describing black and white photos, one of which includes his father as a young, British soldier, stationed in the small northern German town of Westen. Ash uses the photos as a means of imaginative transport: to another time and, seemingly, another world. It’s 1945: the dust has yet to settle from the second world war in as many decades. A most tenuous peace is struggling to take hold. His father is a young man, 26 years old, many years in a long life still to live. Yet it was recent enough that a few from that time are still alive to talk about it. And, of course, Westen still exists. Ash has recently visited the place. The town is now thriving economically. Those who Ash meets are happy to talk to this Englishman whose father was once part of an occupying force. Nevertheless the visit seems faintly portentous as well. One of Westen’s oldest residents shows Ash his war wounds, scars that act as a lingering reminder of what, for him, was an unexpected defeat. “It was completely clear that Hitler would win the war,” the elderly townsman relates to Ash.

Ash is an English historian of some renown whose area of expertise is Europe. His renown is noteworthy: it allows him such close proximity to power that he might be described as a man of political influence as well as a historian. His accounts of post-war Europe are dotted with mentions of time spent with world leaders. He was among the few summoned by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to seek his counsel on the potential reunification of East and West Germany. With a wary eye towards the still recent past, she wondered what sort of country a united Germany would be. A Germany that again seeks to dominate Europe or a Germany that seeks to lead Europe through its liberal democratic example? Helmut Kohl, West Germany’s chancellor at the time, disclosed to Ash the overwhelming sense of responsibility he felt over the prospect of his divided country becoming whole again. He meets with the late Vaclav Havel, the author and playwright and Czechoslovakia’s first post-communist prime minister, first in his apartment in Prague and later at his farmhouse in northern Bohemia. Over beer and soup, he writes, they talked late into the night about the role of the political writer and the risks he or she runs when speaking truth to power. He dined with the late Mikhail Gorbachev at the height of his fame as the visionary political leader of a new and open Soviet Union. His close encounters with the most powerful confirm one of the memoir’s recurring themes: particular individuals can have outsized influence on history’s trajectory.

Other encounters with Europe’s most powerful are less satisfying, although equally instructive. He attends a luncheon in 1994 in St Petersburg at which various Russian politicians are present. A young, ambitious and embittered mayor informs Ash that Crimea, then part of Ukraine, has always belonged to Russia. That young man’s name is Vladimir Putin. The ‘motherland’, he would go on to say, has a duty to the millions of Russians now living in Crimea. The conversation was infused with the threat of an unwelcome promise. The motherland must sometimes forcibly bring home her wayward children. In March 2014, as Ash later documents, Putin’s Russia invaded and then annexed Crimea. Henceforth, it would no longer be part of Ukraine. Threat realized, promise kept. He receives correspondence from Viktor Orban, Hungary’s long-time prime minister, in which he takes umbrage with Ash over his characterization of his government as a threat to the integrity of the European Union (EU).

Indeed, any such threat strikes close to Ash’s heart. He’s a passionate proponent of the EU as the necessary political and economic framework if the entire continent is to have a peaceful, prosperous and, with any luck, liberal democratic future. The reader senses his love of both the continent and the EU, his fervent belief in Liberalism as a political philosophy, as much for its apparent virtues as his fear of the alternatives, which are always lurking in the shadows, threatening to spill over into the mainstream. He is, moreover, an embodiment of the EU’s twin promise of open borders and freedom of movement. He cherishes both because they served redefine what’s possible and to shape who he has become. In addition to English, Ash speaks multiple languages, French, German and Polish and is married to a Polish woman. He has resolved the tension that for so many other Europeans remains unresolved. He’s at once a citizen of England and of Europe.

Homelands has a kaleidoscope quality. Ash’s focus constantly shifts from one short chapter to the next, across both time and space. One chapter might be rooted in his visit to a small, northern German town. Another might be about his time as a student allowed to do research in East Germany when the country was still divided between communist East and capitalist West. He witnesses and writes about the initial strikes in Gdansk, Poland that eventually morphed into the country’s Solidarity Movement. Another examines Brexit, while another examines the fraught status of the continent’s various Muslim populations, especially post 9/11. You get the idea. Yet the book is divided into five sections designed to give it a structure and trajectory that mirrors Europe’s own post-World War Two trajectory. It also gives the memoir a coherence it might otherwise lack. The sections are as follows: Europe ‘Destroyed’, Europe ‘Divided’, Europe ‘Rising’, Europe ‘Triumphant’ and, at last, Europe ‘Faltering’, which brings the reader to the near present.

Ash writes, often movingly, about the role of the ‘memory engine’ in Europe. The memory engine is that which connects the continent’s troubled and often sordid past to the present. It lives in the hearts and minds of those who lived through the horrors of the Second World War especially, but more recent wars as well. The industrial scale slaughter, concentration camps and genocide, the brutalizing occupations and the malign visions of a world order based on Aryan supremacy. It is these uniquely personal memories of the continent’s descent into barbarism that motivated, more than anything else did, the shared desire and vision for a well-integrated European community. A continent united around a series of ideas, promises, and obligations will not descend into the sort of madness that gave rise to Nazism in particular and fascism more generally, and communist-inspired totalitarianism. A Europe divided and a Europe on the cusp of oblivion. This was the idea, the rallying cry that gave rise to the European Union. A united and liberal democratic Europe could not, would not, go back.

Yet, as Ash’s memoir also illuminates, the continent remains as crisis and conflict-prone as ever. The EU is designed to serve as a bulwark against both but has been met with mixed results at best. In addition, an economic and political union comprised of 27 countries is fraught with both challenges and risks. Governing a single country in a hyper globalized economy, while managing a country’s obligations to a wider union is no simple task. The principle of national sovereignty must somehow coexist with the principle of supranational sovereignty. Meant to be mutually reinforcing, the two principles are instead often in tension, or at least made to seem so. Most distressingly, the memory engine about which Ash writes can cut in different ways, many of which are hardly conducive to all countries having mutually harmonious futures. History can be distorted, memories weaponized, especially when cynically manipulated so as to become sources of national humiliation. By the book’s end, Ash and the reader are forced to confront a truth, at once stark and sobering: Europe’s illiberal forces never really went away but the threat they now pose is new.

Europe’s Liberal-Democratic Promise

There has always been something at once aspirational and contradictory at the heart of Western Europe’s liberal-democratic promise. In the wake of the Second World War, it’s worth recalling, the continent was divided between East and West by the so-called Iron Curtain. Eastern Europe was comprised of communist countries, Western Europe mostly liberal democratic countries. According to its most avid practitioners, communism was thought to represent History’s inevitable progression: post-capitalism, post-imperialism and colonialism and post-conflict: appealing ideas in the aftermath of a war that killed tens of millions people and ushered in the age of nuclear weapons. The world made anew and one characterized by political freedom and economic prosperity hitherto never experienced; alienation from one’s labour is a thing of the past. These sorts of ideals were never realized in any of the Eastern Bloc countries, not even remotely so. Nevertheless in the early post-war stages those same ideals constituted a challenge to Western Europe’s still burgeoning liberal democratic order. What if the Soviet Union really was ushering in a new and better world?

Moreover, western Europe could not so easily claim superiority, political, moral or otherwise. Yes Nazism had been vanquished, but not fascism altogether. Spain’s civil war ended with Franco’s victory. His fascist dictatorship would not end until his death in 1975. Portugal would remain a dictatorship until 1974. And the nasty business of Empire was still hanging, like dark clouds, over much of the continent. Portugal would fight colonial wars in Angola and Mozambique. France would fight protracted colonial wars in Algeria and Indo-China. The cruel hypocrisy was obvious, even then: self-determination for the French and its allies but not for those peoples who have lived for so long under their oppressive rule. The same tension has too often characterized France’s relationship to its immigrant communities. As one Algerian Muslim now living in France confides to Ash, “Where is my liberty? My equality? My fraternity?”

Yet the arc of change bent towards Western Europe and its liberal democratic traditions. One common refrain from that time, meant to demonstrate the West’s superiority vis a vis the East, went as follows: people from Western Europe were not clamouring to move to East Germany or Russia or any of the Soviet satellite states. People from the East, by sharp contrast, were sometimes desperate to escape their cloistered and surveilled existence. The walls that separated East from West were not so impenetrable that people living in the East didn’t understand: on the other side there were ways of life that more closely resembled freedom than anything that existed here. A crude yardstick to be sure, but one that had a certain ring of truth.

Indeed, Western Europe, for all of its problems, inadequacies and injustices had infinitely more going for it than did Eastern Europe. Economies were more productive and dynamic. Standards of living were higher. There was something that resembled a free press. Citizens could travel freely; they were free to start their own business. Conversations weren’t being listened to by state authorities. People weren’t one subversive idea away from a visit from the secret police or a stay in the Gulag. Western European countries accommodated protest and dissent in a way Eastern European governments would not countenance. Technologically, the West was leaps and bounds ahead of the East, the effect of which was to make those countries seem even more stuck in a kind of netherworld, dull, stagnant and bleak by comparison.

Thus perhaps the greatest impetus towards liberal democracy in Europe stemmed from the sorry fate of the Eastern Bloc. Despite the many failures and limitations of communist rule, there was a sense too of solidity. Communism wasn’t going anywhere. That this belief endured for so long reflected a failure of the imagination. For the cracks started to appear; the cracks turned into fissures that spread their way across the entire Eastern Bloc. It began with Poland’s solidarity movement in 1980, led by Lech Walesa, who would become the country’s first post-communist President in 1990. The Berlin Wall – separating East and West Germany – was breached on November 9, 1989 by East Germans hoping to flee West. There wasn’t a shot fired by East German security guards. Glasnost and Perestroika was cause and consequence of a new spirit of openness and tolerance in Russia especially but in other former Soviet satellite states, too. Soon enough there were revolutionary movements in the Baltic states and, before long, Russia itself. It didn’t take long before communist regimes fell, like dominoes, one after another. What was believed to be as solid as steel – the power of communist governments over their cowed citizenries – turned out to be as fragile as fine china.

Ironies abounded during this period of accelerated change and upheaval. Ash, the ever astute chronicler, is skilled at uncovering them. Perhaps the most salient: capitalism, as it turns out, was more revolutionary than communism ever was. Communist societies, in many key respects, tended to resemble that which came before: architecturally drab and technologically lagging. Work life, although hardly uniformly, was often described as drudgery by those who engaged in it. Now, all across Eastern Europe, it was post-communist capitalism that made familiar promises: a new and better life, new freedoms, a type of material prosperity never before experienced. Heady times even though, as Ash makes clear, there were signs, many ominous, that the transition to capitalism would engender its own discontents. To begin with, the transition was never seamless or painless, as it typically involved the imposition of structural adjustment programs. The pain associated with such policies was compounded by sometimes staggering levels of corruption. For it was the communist elites who were generally the most financially and politically rewarded in the transition to capitalism. Moreover, the transition was not preceded or accompanied by any sort of truth and reconciliation process designed to hold those who abused their power accountable. Rarely had liberation engendered so much resentment.

In a country like Poland, it was also the promise of joining the EU that eventually served to sow seeds of discord. Herein lies another irony, or something that feels ironic: those who resisted joining the EU were often conservative and Catholic. They often lived in rural areas, beyond the burgeoning cities, and regarded the EU as too secular, too godless and too remote. Capitalism and the EU both fostered the liberalization of social mores and a society too consumed by the shallow satisfactions of materialism. Communism, many would say, had its problems but at least society was more predictable and people less distracted by the desire for new things.

One last irony, although to call it that is perhaps to minimize the tragedy at the heart of it. The sudden collapse of the Eastern Bloc and Western Europe’s steady momentum culminated in The Maastricht Treaty. Signed in 1992, the treaty established the European Union. This treaty, as Ash makes clear, was a landmark in the history of the continent. It either established or set in motion many of the principles and features we associate with Europe today. It led to the establishment of Europe’s single currency, the Euro. It introduced the notion of EU citizenship and gave more authority and power to the European Parliament. The benefits of such closer integration were manifold: privileged access to the biggest market in the world and thus increased standards of living; freedom of movement for citizens of member countries. The inspirations for the EU were many, but none more important than the desire to avoid the calamity of more war on European soil. Ever closer integration would minimize the threat of conflict. This is the triumphant Europe about which Ash writes.

Alas, the same year The Maastricht Treaty was signed – 1992 – the former Yugoslavia descended into genocidal chaos. The treaty, for all of its importance and promise, could not dispel the ghosts of the past. They would continue to haunt Europe.

Crisis After Crisis

Such is the nature of crisis in Europe: one country’s problems are almost impossible to contain. They invariably have rippling effects that extend to the whole of the EU, if not the entire continent. The road to the Great War began with a single gun shot aimed Austria Hungary’s Arch Duke Ferdinand. The empire’s response – an ultimatum directed at Serbia, followed by the declaration of war – drew the rest of the continent into a morass from which no country felt it could extricate itself. Soon battle lines were drawn, diplomats recalled, troops mobilized and frontiers crossed. Eventually all of Europe became a killing field. This sort of full-scale, continent-wide military crisis may be a thing of the past. As Ash demonstrates, however, crises come in different forms and many have the power to strike at the heart of the European Union, if not all of Europe.

In 2010, Greece’s national government declared that its budget deficit was more than 13% of its GDP and public debt more than 120%. These amounts exceeded the limits spelled out in the Maastricht Treaty, which insisted on 3% and 60% respectively. Greece’s financial problems were also the problems of the EU. There was no way Greece’s government could be left in a position in which default on its debt was a likely outcome. Yet the possibility of what was referred to a “doom loop’ was real: nearly bankrupt banks would lend to a nearly bankrupt Greek government, at ever higher interest rates. The government would not be able to service its debts, thereby creating a need for further loans from the already compromised banks at ever higher interest rates. This would constitute a doom loop, one instance which would create a larger, even more insidious sort of threat: that of contagion. If one government defaulted on its debt and many banks suffered as a result, the same dynamic could happen in other European countries. The continent’s economic union would be left in tatters; without an economic union, the political union would dissolve as well.

Thus the question of Greece’s immediate future was also the question of the EU’s future. Put another way, in the form of a question: How to protect Greece from financial collapse without endangering the EU’s future? The question goes to the heart of a tension running through the heart of the EU. The EU is designed be a union among free and equal sovereign states. The union supersedes national sovereignty without compromising such sovereignty.

Yet Greece’s economic crisis required that France And Germany, in particular, be able to exercise outsized influence on Greece’s internal politics. Bailouts for Greece? Many Germans scoffed at the notion and took to scolding Greeks like a stern parent might scold a recalcitrant child. Germans cannot be responsible for a country whose government and people cannot live within their means. In the end, bailouts were given but under the strictest of conditions: public sector spending on education, health care and pensions all had to be slashed. Greeks, not at all surprisingly, resented the role countries like Germany were assuming in their own country’s affairs. What happened to the principle of national sovereignty? Even more infuriating was that much of the “bailout money went to foreign creditors, including those German, French and other banks.” The memory engine about which Ash writes was cutting in a way the EU was supposedly designed to avoid. Old wounds were made to feel fresh again. Nasty forms of nationalism reared their ugly heads. That which was supposed to bind countries in a mutually beneficial pact was suddenly seeming as though it was nothing of the sort.

“A New Iron Curtain”

Once again, Europe’s progress is stalled by a crisis of continent-wide proportions. An understandable impression is that it has always been thus, as though the continent is stuck inside a Greek tragedy, doomed to repeat the same history again and again. Periods of peace and relative stability are interrupted by periods of upheaval and war. Countries turn on each other, with often dire consequences. The risk in that sort of analogy is missing what’s new and novel in a rapidly changing world. Witness the fraught relationship between Europe and the refugees and migrants — many from Sub-Saharan Africa but many others from war torn places like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan — who attempt to flee desperate circumstances for the shores of Europe. ‘Shores’ is the operative word: one of the most tragic and recurring scenarios involving Europe and the rest of the world is of people in the most unworthy of sea vessels, in numbers that make the heart shudder in despair, unsuccessfully attempting to cross the Mediterranean for the shores of Spain or Lampedusa or the English Channel for the shores of Britain. That it is water which must first be crossed is at once representative and symbolic of a vital change in the history of Europe. As Ash writes, the iron curtain separating people no longer crosses through the heart of the continent, separating East from West. The iron curtain is now the barriers – water first, walls and barbed wire fences second – that separate Europe from the South.

Ash, to his credit, inserts himself in these still unfolding human and political dramas. He might be a decorated Oxford Professor, but he can never be accused of writing from inside the ivory tower of academia. In one of the memoir’s final chapters he writes about conversations he had with Moroccan teenagers in a hotel located in Ceuta. They are among the few who succeeded in eluding Spanish border authorities for long enough that they had a chance of being allowed to stay. The young men tell Ash they had nothing to lose when the choice was made to flee Morocco and attempt the dangerous business of gaining access to Spain and, after Spain, elsewhere in Europe, perhaps Germany or France, where securing employment might be slightly easier. No matter what hardships they endure, they would do it again. This is how hopeless they felt their prospects were in Morocco and it’s the same dire calculation countless others make on a daily basis. In an age of climate crisis and breakdown, this sort of scenario will become ever more commonplace.

Ash writes of the different perceptions of those brief windows of opportunity for refugees and migrants. For those fleeing places like Morocco: the chance at a sort of freedom more worthy of its name. The opportunity, however difficult to realize, to build a better life, to help family who might remain at home. For far right parties like Spain’s Vox the surge of people constitutes an “invasion”, the obvious implication of which is that the country is or should be engaged in a type of war. The invading hordes must be stopped!

Indeed this is the prevailing sentiment among Europe’s most far right parties, all of whom are riding waves of growing support. Many such parties are dominating or threatening to dominate countries within the EU. Ash devotes an entire chapter to the examination of Hungary under Orban and the Fidesz Party, which he leads. Alas, other parties in other EU member states have followed suit. Spain has Vox. France Marie Le Pen’s National Rally, Germany the AFD, Poland the Law and Justice Party. The list goes on. It’s as though they have read the same populist playbook and adopted the same strategies. Manufacture grievances, highlight threats to a country’s traditional order and where possible, revise electoral maps with a view to securing future election victories. Such parties tend to take advantage of the EU’s largesse while simultaneously castigating it as too liberal, too bureaucratic and interfering, too remote from the lives and concerns of the people it purports to represent. From this perspective, Europe can appear as a continent under siege, not from forces from without, but rather from reactionary, often racist forces within.

Ash laments the rise of this sort of right wing, faintly fascist populism, but is at a loss as how to stem the tide. Still he is not without optimism. The tides of history change, after all, often unexpectedly and in more humane, equitable and democratic directions. As any good historian will tell you, the future is open, unpredictable. Moreover, the EU and the continent’s liberal democracies are not only resilient but also inextricably linked. The liberal centre is holding firm in some countries, if not in all. Yet the history and threats Ash documents raise a possibility that he is likely loath to consider: the EU may survive but many of the countries that comprise it may no longer be all that liberal or democratic.