Watershed Moment

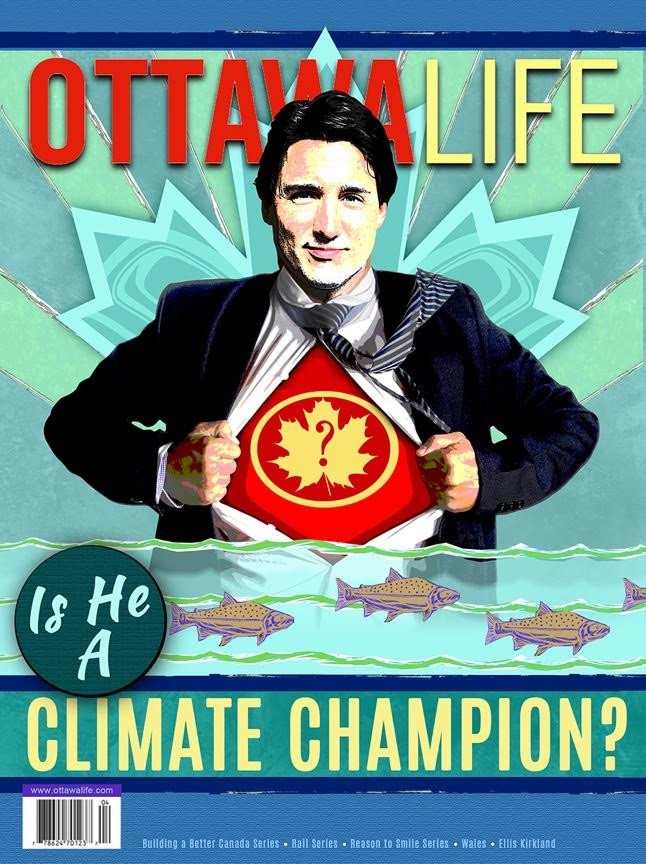

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been actively putting forward a different approach to governance: one that champions transparency, freshness, action, something that says this time it’s different.

One of his ministers in particular, seems to be the embodiment of that sentiment. There’s a positive vibe when entering Environment Minister Catherine McKenna’s Centre Block office on Parliament Hill. Maybe it’s the young staff milling about, busy but polite, well dressed and intelligent. Or maybe it’s the tremendous birch bark canoe hanging from the ceiling, an emblem of Canada languidly floating over the bustling office.

It’s fitting then that McKenna associates herself with such a symbol. With her at the helm, she and Trudeau aim to steer Canada away from a fossil fuel based economy to return to one that works in harmony with the environment.

McKenna is a lawyer by profession and has experience in government, business and the NGO sector. She is not only calm, confident and focused, but she is also on top of her file, and fully aware that her role as Canada’s Environment Minister comes at a critical time.

“We have a Prime Minister who’s absolutely committed to climate change. He believes like I do, that this is the biggest challenge of our generation, and that we have an obligation to take action,” said McKenna.

She believes that unlike the promises in Kyoto, and unlike the past Conservative government, this time, it really will be different. When asked what makes it different, she was clear.

“I have young daughters and if we don't take steps now to fix these problems, their future will be very different. I got into politics because of my concern for my kids and the problems with how we were treating our greatest resources and the planet.”

The problem is that the Liberals have many, and sometimes conflicting, promises to keep. Climate commitments, their promises to First Nations communities, and their guarantees to industry all hover uncomfortably, an unbalanced mixture that will surely test their leadership in the coming years.

But moving on climate change was one of Trudeau’s first big moves, and certainly one of his most visible. Just over a month after he was elected, he went to Paris for the snappily named United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) for the 21st annual Conference of the Parties or (COP21). There, 195 countries signed an agreement to commit to keeping the world from warming above two degrees from industrial levels, a limit that if passed, scientists predict catastrophic consequences. Canada, for its part, has held to the previous Harper government commitments, and pledged to cut its carbon emissions by 30 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030.

Promises roll off the tongue with ease, of course. Actions, however, are harder to implement, a reality that McKenna encountered in her first day of taking office. Fresh to her role as Environment Minister, she was tasked with whether to release billions of litres of raw sewage into the St. Lawrence River, and she needed to choose quickly. Montreal’s Mayor Denis Coderre was insisting on its necessity for the safety of the city, while others cringed at the thought of sewage flowing through their water. Talk about a first day.

In the end, she decided to do it.

After the fact, Montreal released the results of their water quality testing, which showed bacteria levels akin to those during heavy rainfalls when sewers overflow into the river, and therefore not far out of the ordinary.

In the end, the controlled release got a go-ahead based on McKenna’s consultations with scientists, and from precedent, making it a fact-based decision. Unfortunately, Indigenous groups were not consulted prior to the release. Mohawk Council Chief Clinton Phillps in Kahnawake, whose community would be directly affected by the sewage, was highly critical of the dump, saying that he had only heard news of the decision in a quick call from McKenna right before the release.

Afterwards, in light of their concerns, McKenna sat down with Kahnawake’s Mohawk Grand Chief Joseph Tokwiro Norton and Phillips to discuss how she should move forward when dealing with First Nations communities.

“To be fair, we were somewhat critical but we also recognize that she just came into office and was thrown into this issue the day before heading to the Paris Climate Change negotiations. We welcome her commitment regarding these things,” said Norton. “She’s a very sincere person, but the issue will be how convincing she can be with other ministers to work with Kahnawake and other First Nations across Canada.”

According to Norton, the Kahnawake Mohawks and other Mohawks in the region have a long history of butting heads with their neighbours. Due to their geographic location, they have the rare position of being directly in contact with Canadian, Québec and U.S. governments on nation- to-nation negotiations on a variety of issues. Now with Trudeau’s and McKenna’s promises at hand, the Kahnawake Mohawks are in a prime location for the federal government’s engagement with First Nations, and they’re optimistic that further interactions can be constructive.

“The Trudeau government has made a pledge to take a very different approach regarding Aboriginal affairs. Hopefully it’s not all talk. They are going to need a coherent and clear understanding that Canada and Kahnawake and Canada and other First Nations are embarking on a process that is no longer business as usual. It’s going to take courage and creativity to achieve their goals. We’ll have to wait and see,” Norton said.

McKenna now has an Indigenous advisor on staff, and says that in hindsight, the sewage release was a learning moment for her as a minister; she realized that in the future she needed to have a framework for how she will approach difficult decisions.

“Listening and learning, and then acting when you have all the evidence and facts or the best information at hand, is very important to me,” said McKenna.

One major element she has to consider is Trudeau’s promise to tax carbon emissions.

Provinces in some cases have taken the lead on this. B.C. plans to tax carbon emissions at $30 a tonne, whereas Alberta has already set a cap on its greenhouse gas emissions from its oilsands to 100 megatonnes a year, and is also introducing a $20 carbon levy in 2017. Québec has been involved in an emissions cap and trade system with California since 2013, a system that Ontario’s Wynne government will now join, along with implementing other measures such as incentivizing electric vehicles.

But some experts don’t believe a hodgepodge of singular provincial regulations will do the trick, because some might choose to opt out completely. McKenna acknowledged that the northern territories expressed a carbon tax would threaten their diesel-based lifestyle. Saskatchewan, for its part, has been playing hardball, arguing that its carbon capture program will be enough of a contribution to Canada’s efforts to reduce its emissions.

Jeff Rubin, previously a chief economist for CIBC World Markets, argues that the only way to reach Canada’s Paris target is to implement a substantial national carbon tax.

“If it doesn’t cost to be dirty, then it doesn’t pay to be green,” said Rubin.

Rubin argues that if a national tax isn’t implemented, Canada will miss the 2020 target from anywhere from 120-150 megatonnes, and the 2030 target by as much as 300 megatonnes, which would constitute misses by 50-60 per cent.

He added that a key element to getting all provinces to sign on would be to level the playing field for the natural gas and fossil fuel industry in North America and apply a cross-country carbon tax.

Talks are underway between Canada, the United States and Mexico, but the outcome is murky so far.

A national tax may seem like the simplest route to curb our emissions, but adding stress on an already limping oil and gas industry isn’t just putting businesses at stake, but also the people who depend on those resources for their livelihoods.

This is why Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall argue for pipelines, they believe they are the only life rafts that will buoy their economies through troubling times. And although some Canadians fear pipeline expansion, Canada’s National Energy Board (NEB) has approved both the Energy East Pipeline, a project that would potentially open up the oil supply form Alberta to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline, that would bring oil from Alberta to the docks in Vancouver.

Both are meant to bring Canadian oil to Asia and Europe, markets that are meant to be more eager than the United States, who, thanks to their shale fracking boom, no longer rely heavily on Canadian oil. Trudeau is not about to leave those markets out of the question. He’s stated that he believes new pipelines are necessary, and that the transition away from Canada’s fossil fuel economy should be paid for by, ironically enough, the fossil fuel industry. But he can’t jump the gun on pipelines either, because pipelines do spill, and they will expand the oil sands, which is the country’s highest emitter of greenhouse gases.

That’s why the Liberals have implemented new interim measures to review major resource projects that include the consultation of Indigenous groups, as well as measures that weigh a project’s potential environmental impact. Along with these measures comes significant delay.

Conservative Environment Critic Ed Fast says that adding more hoops to jump through for projects that have already been approved by the NEB is hurting Canada’s economic prospects.

“They have injected an unprecedented uncertainty into the economy. The investment community has taken notice and that they are considering pulling money out of Canada,” said Fast.

Although Fast strongly welcomes the growth of the clean tech industry, he doesn’t believe that this could replace the contribution from the current energy sector.

McKenna has different views on innovative green technology. She referenced a study recently put out by the International Renewable Energy Agency stating that going greener could save the global economy over $4-trillion a year by 2030.

“I’m talking with all sectors, all industry associations, and everyone’s excited. This is an opportunity, and they recognize that we need to take action,” said McKenna. “It was businesses that were ahead of government on this. When I hear businesses saying yes, put a price on carbon, I know it’s good news. Businesses want certainty.”

In Paris, Trudeau also committed to participating in Mission Innovation, a program spearheaded by Bill Gates that includes 20 countries who have the intention to accelerate the development of the clean energy sector.

“We have a very serious process underway, with a timeframe,” said McKenna. She pointed to the federal government’s workings groups that will present solutions in the fall on how to reduce emissions in building, vehicles, the oil and gas sector, carbon pricing, adaptation, clean tech jobs and innovation.

Despite these steps forward, there are some other voices in Canada that claim the Liberals aren’t moving away from carbon emitting industries fast enough.

Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson travelled to Ottawa, along with leaders from First Nations communities to protest the Trans Mountain pipeline. Robertson argued that the expansion of the pipeline, which the NEB approved with only 157 conditions to meet, would increase tanker traffic by seven times in his city, multiplying the possibility of oil spills and the amount of emissions in Vancouver to an unacceptable amount.

Montreal, along with the Government of Québec, have openly blasted Energy East, stating that the project cannot go forward due to environmental risks, no matter what the cost to Alberta. Countless environmental groups around the country are vehemently opposed to any sort of pipeline, oil sands, or liquid natural gas expansion.

It’s clear that Canadians need some unification on what direction to take climate change policy, and nowhere was that clearer than when Trudeau met with Canada’s premiers to create his pan-Canadian framework on climate change in early March. This meeting was meant to delineate Canada’s climate strategy, but it resulted in delaying to finalize the plan in the fall.

“Canada is a federation, so we have to respect the right for governments to make the decisions they make,” said McKenna. She added that it’s more a federal responsibility to set the structure, and to listen to the unique needs of the provinces.

The truth of the matter is that if Trudeau and McKenna expect to hit their targets, there have to be major changes somewhere.

David Hughes, a scientist who worked for the Geological Survey of Canada for over 30 years, recently released a report called Can Canada Expand Oil and Gas Production, Build Pipelines and Keep Its Climate Change Commitments?

Hughes calculated a best-case scenario, which would allow for a 45 per cent expansion of oil sands production under Alberta’s emissions cap and the introduction of only one liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant in B.C. by 2030. Although Hughes’ calculations assume just one of the five LNG terminals B.C. aspires to build go ahead, he argues that even with these relatively low expansions of emissions, the rest of the national economy would have to shrink its emissions by 47 per cent in every sector over 14 years; an outcome that he finds almost impossible without great economic damage.

In B.C., Premier Christy Clark has promised several LNG plants as a way of paying off the province’s debts and creating jobs, and although several have been approved by the NEB, none have been built. LNG plants have remained in limbo for the same reasons new pipelines have, no one can find a consensus on if they should be built.

One shining example of this indecision is found in northwest B.C.’s Skeena Watershed. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) approved an $11.4-billion Pacific Northwest LNG plant, backed by Malaysian state-owned energy company Petronas.

Last year, Jonathan Moore, a professor from Simon Fraser University who specializes in aquatic ecology and conservation, studied the area and the effects of building and LNG plant where it was proposed. He then penned a letter, signed by 130 international scientists, addressed to the federal government, contesting the science reviewed by the CEAA.

Along with that letter, the proposal gained national attention this year thanks to the the efforts of the Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition (SWCC).

Shannon McPhail, the executive director of SWCC, said that the area proposed for the plant is the site of the second largest salmon run in Canada, and the rivers near the proposed site on Lelu Island within the watershed are where every year, anywhere from 300-million to 1-billion salmon come to spawn. She, along with many scientists, argue that the LNG plant would be catastrophic for the salmon’s ecosystem.

The salmon are a $110-million industry for the people in the Skeena Watershed, a community heavily represented by Indigenous peoples.

“When the salmon come, the entire community shuts down in a way, because we’re all out fishing, pulling nets, cleaning, soaking, smoking, canning, filleting,” said McPhail.

“Every leaf, and every needle from every tree in this watershed has salmon in them. If you cut down a tree and look at its growth rings, you can estimate how many salmon returned that year by the size of the growth ring: the more salmon that come up the bigger the forest grows.”

Petronas offered a $1-billion deal to the Lax Kw’alaams people of the area as compensation, which was in turn rejected.

McKenna admitted that she’s aware of the potential danger to the salmon, and also acknowledged that there will be significant emissions from the plant. The CEAA reported that if built, the plant would emit 5.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide yearly.

The B.C. government, on the other hand, justifies the plant’s construction on the basis that the natural gas shipped overseas would help ween China off of burning coal for energy, a big hitter on the global scale for greenhouse gas emissions.

Now tasked with making a decision on the plant, McKenna said that the federal government will weigh its choice on the best available science, evidence and facts. In reality, the decision is more complicated than just science and facts. Trudeau’s cabinet must consider it’s promises to Indigenous groups, to climate commitments, to industry, to the needs of B.C.’s economy, their own popular opinion, and the people’s lives who will be affected by the plant itself.

“If they were to approve this project they would send the message to First Nations and to all communities in the area that Malaysia and Petronas are more valuable to them their own citizens, and certainly more valuable to them than keeping their word about climate change,” said McPhail, who admitted that not even she would want to have to make such a decision.

It would take a miracle to make everyone happy, and at this moment, it’s unclear which direction McKenna’s canoe will take us. She and Trudeau have to choose to move the country forward, without leaving half the country behind. Whatever the direction, no doubt it will be a “watershed moment” for the Liberals and for Canada itself.

Correction notice: We at Ottawa Life would like to bring to notice the following corrections that were made from the printed version of the story.

The Skeena Watershed is not the second largest estuary, but the second largest salmon run in Canada, and it is the rivers around the area where the salmon come to spawn. This is also quoted as a direct quote from Shannon McPhail in the printed article, although it was a paraphrased. This was an error on Ottawa Life's part.

The SWCC did not write the letter to the federal government as previously published, but rather professor Jonathan Moore was the author.

We also did not specify that Petronas offered the $1-billion buyout to the First Nations Lax Kw’alaams people in Skeena area, of which they rejected.