What does the government’s promised ‘disability lens’ really mean?

The last minute Liberal election commitment to apply a disability lens to all federal government decisions was both fought for and welcomed widely by the disability community across the country.

But it’s easy to promise. Now the government must deliver.

The pledge for a disability lens meets its first test in a recent challenge to Canada’s medical assistance in dying (MAiD) legislation. The most important safeguard for those with disabilities was recently removed from the assisted dying legislation by the Quebec Supreme Court, which struck down the prerequisite for a “natural, reasonably foreseeable death.”

The Liberal decision announced during the election not to appeal this ruling, and to expand the existing law to bring it in line with the ruling, is a slap in the face to disabled Canadians. It denies them both a good life and a good death.

How so?

Human rights are primarily about levelling the playing field and protecting minority groups. Canada’s largest minority group is disabled people — one in five Canadians, according to Statistics Canada. By no stretch of the imagination have our federal and provincial governments been fair to them.

Every horror experienced by Indigenous people and ethnic groups in Canada is still happening to those of us with disabilities.

We still have the equivalent of residential schools for disabled people. We still sterilize disabled people. We still separate them from their families. We still put them in solitary confinement in our schools and services. We still make them the butt of our jokes. We still tolerate their chronic poverty and high unemployment, which is double the national average.

We still begrudge disabled people basic supports that enable them to contribute to society.

Those are some of the tangible barriers that deny a good everyday life to disabled Canadians. Their lives are also saturated by patronization, mockery, cruelty, low expectations and ignorance. And when it comes time to die, they face, along with the rest of Canadians, a lack of palliative care and hospice resources.

It is no wonder that disabled people fear being forced toward an early death. That fear is justified.

Sean Tagert of Powell River chose medically assisted death in August because he could not get the home care that would keep him close to his son. "Ensuring consistent care was a constant struggle and source of stress for Sean as a patient," read the Facebook post in his honour. “The few institutional options on hand … would have offered vastly inferior care while separating him from his family, and likely would have hastened his death.” Sean had ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease).

The family of Alan Nichols worries he too was pushed toward an early death. They say the current MAID safeguards did not work for him, that he was not facing imminent death, that he was mentally ill and unable to give informed consent.

These are not isolated instances. Disabled people report having trouble accessing basic medical care or being offered medically assisted death instead. Parents are told that it can arranged that their disabled child need not ever wake up from their surgery.

Assurances that removing safeguards won’t affect you are meaningless if you live in an environment where you must fight for your basic rights every day, everywhere.

The current MAID legislation was a fine balance between respecting the rights of people with disabilities and seniors while honouring the wishes of Canadians to choose a physician assisted death. The legislation is three years old.

What is the rush to change it when it has not been properly evaluated, when unintended consequences remain unstudied? Municipal zoning amendments can take longer to amend – and lives aren’t at stake. By contrast, disabled people have been waiting for Canada to fulfill its obligations to them since Confederation — more than one hundred and fifty years ago.

Applying a disability lens doesn’t mean the obliteration of the existing safeguards of MAID legislation. It means addressing the lack of community supports and palliative care resources for disabled people and other vulnerable Canadians.

An essential and fair first step in addressing an imbalance that has gone on far too long is restoring the safeguards to assisted dying legislation the Quebec Supreme Court took away.

By David Roche and Al Etmanski

David Roche is a pioneer of disability culture, author, actor, speaker and long-time activist in the facial difference community. See davidroche.com, loveatsecondsight.org, facebook.com/HappyFacethemovie

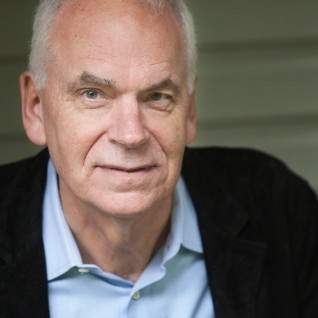

Al Etmanski is an author, and community organizer. He has been a disability advocate since the birth of his daughter four decades ago. He has led the closure of institutions and segregated schools and proposed the creation of the world’s first Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP.) His new book The Power of Disability will be published in February 2020.