When Labels Aren’t Just for Soup Cans & Rolodexes Just Aren’t Enough

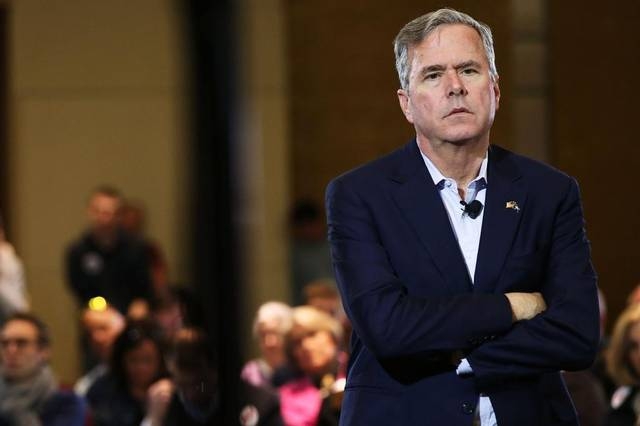

South Carolina is an American state whose reputation for political trench warfare precedes itself. Inside a crowded North Charleston auditorium as he stumped for his brother, Jeb, in South Carolina, former president George W. Bush reminded his audience that, while “There seems to be a lot of name calling going on but, I want to remind you what our good dad told me one time: labels are for soup cans.” However, when the polls closed, the results indicted that, contrary to former president George W. Bush’s words, labels weren’t just for soup cans.

As the 2016 Republican South Carolina primary ended, Jeb Bush had a less than stellar finish. In fact, he came in fourth place with approximately 7.8% of the vote. Donald Trump, the larger than life businessman and media personality, won the South Carolina primary by receiving a robust 32.5% of the vote. The two junior U.S. senators in the Republican race, Marco Rubio (from Florida) and Ted Cruz (from Texas) trailed Trump by 10% but had a photo finish between themselves for the race’s second and third place positions with Rubio ultimately winning 22.5% of the vote and Cruz winning 22.3%. In sum, even the former president’s eleventh hour return from the political abyss to campaign for his brother proved to be no more than an exercise in futility.

By the end of that fateful evening, Jeb Bush threw in the proverbial presidential election campaign towel: he suspended his campaign. And thus the possibility of a third Bush moving into the White House in 2016 was no more. The ultimate establishment Republican presidential candidate lost to an opponent who — because of his inflammatory comments, boisterous behaviour and sparse policy details — is shaping up to be the ultimate Republican anti-establishment candidate.

By the end of that fateful evening, Jeb Bush threw in the proverbial presidential election campaign towel: he suspended his campaign. And thus the possibility of a third Bush moving into the White House in 2016 was no more. The ultimate establishment Republican presidential candidate lost to an opponent who — because of his inflammatory comments, boisterous behaviour and sparse policy details — is shaping up to be the ultimate Republican anti-establishment candidate.

As such, Trump wasted no time proving that labels weren’t just for soup cans in South Carolina. His long-standing labeling of Jeb as “low energy” proved itself to be a surprisingly effective tactical trope on the road to South Carolina. Effective indeed, especially since, as many cynical media critics aptly noted, Trump incorporated a triumphant escalator ride from the lobby of Trump Tower into the building’s atrium and food court, the site of his presidential announcement which occurred more than half a year in advance of South Carolina’s primary.

By the time that the Bush campaign realized that the Trump campaign wasn’t merely a political sideshow that could easily be dismissed as little more than the flavor of the week, it was too late. The Bush campaign created numerous electoral scenarios, but none predicted the visceral and systemic anti-establishment momentum that Trump’s campaign reflects. Even worse, Jeb Bush and his campaign failed to alter their strategies once it became clear that Donald Trump was morphing into a conservative populist juggernaut — albeit one whose rhetoric has largely been interpreted as initiating a state of civil war within the Republican party, stoking fears that his divisive campaigning could torpedo the prospects of the GOP winning the White House not just this November, but also for the foreseeable future.

Mary Matalin, a well-known senior Republican political insider, once said that “the maximum goal in professional politics is ‘No surprises.’” As was implied earlier, that mantra cannot be applied to the 2016 Republican primary race — both up to and then beyond South Carolina. But you would be hard-pressed to find tangible evidence that the Bush campaign playbook took note. In fact, the Bush campaign playbook appeared to be set in stone and, accordingly, was anything but agile. Therefore, when surprises on the campaign trail occurred, the Bush campaign was unable to counter its opponents’ messaging and lacked an action plan to get its own candidate’s message out to voters. Consequently, the Bush campaign broke what Matalin called “Cardinal rule 101 of politics: Never let the other side define you.”

To make matters worse for Jeb Bush, money didn’t talk. The Bush campaign ran the epitome of what many call an “insider” campaign fundraising strategy. Simply put, an insider campaign fundraising strategy can be classified as as a form of Rolodex fundraising in which fundraising is reliant upon connections and contacts and wherein the donations raised are raised in large increments. Front and center here are the so-called Super PACs which, in a nutshell, are recently developed fundraising committees that are legally entitled to raise and then spend unlimited sums of money accumulated from individuals, corporations, associations and unions to publicly promote (or dispute) political office seekers and incumbent officeholders. The catch is that these Super PACs can neither coordinate with the candidates they are advocating for or against, nor can they donate their funds to said candidates.

But for Jeb Bush’s campaign and the Jeb Bush friendly Super PACs, there was another catch: the approximately $150 million dollars they raised was largely in vain. Much of that money was spent on crafting and then disseminating political advertisements which simply fizzled. The labeling of Jeb Bush as “low energy” coupled with the fact that Jeb Bush’s campaign largely failed to alter its campaign tactics to effectively address the insurgent Trump campaign and the fundamental anti-establishment sentiment in this presidential election cycle ensured that, even before the South Carolina Republican primary signaled the death knell of the Bush campaign, the writing was already on the wall. In essence, the lesson learned from the failed 2016 Jeb Bush presidential campaign is this: when running for president, labels aren’t just for soup cans and Rolodexes just aren’t enough.